The 35 Best Films Of The Decade

From the era-defining to the overlooked, these were our favourite films of the 2010s.

Only one film on this list — Moonlight, for reference — won best picture at the Oscars. Who cares!

Awards are often wrong, as are lists: even writing a retrospective on the decade proves too near-sighted to really make judgement, if judgement can even really be made to begin with. Is Coco a better film than Melancholia? Nothing brings me more joy than Mamma Mia 2: Here We Go Again, but are we judging joy or ‘bestness’?

And yet we must list! We must. And so I have: I went for the films that have stayed with me, even if that means just one scene, sticking to one per director.

Here are the 35 best films of the decade, in chronological order, with a seeming preference for 2017 and 2018. Sorry for not having seen your favourite, otherwise I’m sure it’d be here.

Honourable mentions: Beginners, The Master, Before Midnight, Inside Llewyn Davis, My Life As A Zucchini, 13th, Your Name, God’s Own Country, Blade Runner 2049, Coco, Suspiria, Annihilation, Paddington 2, Shoplifters, Mamma Mia! Here We Go Again, Portrait Of A Lady On Fire, The Master, The Farewell, et al.

The Social Network (2010)

Increasingly prescient, The Social Network paints Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg as a power-hungry man ready to commericalise human connection at the destruction of his own.

Writer Aaron Sorkin’s tendency towards walk-and-talks has long leaned robotic, and Jesse Eisenberg runs with it as Zuckerberg, in the best performance of his career. But Zuckerberg isn’t necessarily the most ruthless man at Harvard — just the luckiest.

Director David Fincher masterfully creates a gloss of arrogance for them to live in, where dick-swinging rowing matches are set to Grieg, and a hoodie can’t keep you warm from the cold of wealth. Unlike other films that get a little lost in the glamour, Fincher never indulges it or treats it with too much fun.

As Facebook’s control of our political landscape continues to shape our world for the worse, The Social Network is a reminder that deceit and lies lay at its core.

A Separation (2011)

A Separation spreads its empathy and judgement across its many characters, all forced to live by compromised morals in contemporary Iran.

A chain-of-events creates a larger legal battle than the proposed divorce at the film’s beginning, when Simin’s husband Nadar refuses to leave the country with their child, due to his father’s health. Their divorce isn’t granted by the state, and they unofficially share custody as Simin returns to her family.

A complex narrative twists and turns as the main middle-class family collide with a poorer, much more religious one; the film’s quick, ever-evolving pace and camera work is claustrophobic, and the pains to breathe envelop the lead’s bodies. Director Asghar Farhadi creates an agonising experience — one you won’t soon forget.

Weekend (2011)

Weekend sears with the pain of self-hatred, as a gay club hook-up becomes a whirlwind 48-hours when Russell (Tom Cullen) meets art student Glen (Chris New) just before he moves overseas.

Largely improvised, Weekend‘s close and quiet scenes invite us in to see queer men create ‘something’ together. Desire and longing are largely the language of queer cinema, and we rarely see a film devoted to this kind of intimacy.

Careful, considerate, and lead by Cullen’s brilliantly broken Russell, Weekend is an incredibly romantic film that doesn’t shy away from nor overstate the challenges of both traumas and annoying behaviours alike — they’re normally linked, after all.

Director Andrew Haigh went on to create HBO’s Looking (unfairly billed as ‘Girls but gay men in San Francisco’), but Weekend says more than it did in two seasons. Quality, not quantity.

Holy Motors (2012)

Utterly bizarre, Holy Motors operates to its own logic. A man (Denis Lavant) is driven across Paris in a limousine, putting on various disguises: he acts out 12 scenes in the real world, varying from the absurd to the bloody. It’s unclear when he is and isn’t acting, or for what purpose or audience — we see no cameras.

Moving and laugh-out-loud absurd in the same beat, Leos Carax’s Holy Motors is a rare, non self-congratulatory ode to cinema. It doubles down on the unique strange magic of losing yourself to the logic and feeling of a film, even while being aware of its artifice.

Unsettling and moving in each scene (again and again and again), it wonders why we’re so enamoured with false emotions, and the threads between genre, bouncing between thrillers, musicals, big-budget-by-the-numbers dramas and mumblecore meditations.

Plus, excellent scenes with Eva Mendes and Kylie Minogue.

Spring Breakers (2012)

The perfect Instagram-crime spree, before Instagram took off. Spring Breakers is a pop-culture event far bigger than anything trash-bag director Harmony Korine had made before: by casting a group of Disney-adjacent teen stars as his girls-gone-criminal in their efforts to get money for spring break, Korine tapped into a meta-narrative of childhood actors going sexy and gritty to throw off their past.

Casting Christian Selena Gomez as moral compass Faith (yes, really) is so-cliché it works and James Franco’s (not) Riff Raff impersonation is a sight to behold, but its the montage of violence and robberies set to Britney Spears’ ‘Everytime’ that defines the film’s trash-into-treasure free-fall.

Worries of taste are thrown out the window in favour of Tumblr aesthetics. The result is a film that often feels like a music video; stretch out the hedonism for too long, and things descend into madness.

You can see Spring Breakers lasting influence across not just our influencers, but on HBO’s Euphoria. Before he struck gold, creator Sam Levinson tried and failed to replicate Korine’s style with the limp Assassination Nation, which was too wrapped in appearing on-trend when Spring Breakers predicted it.

It’s era-defining, for better or worse: sprang break foreveerrrr.

Zero Dark Thirty (2012)

When both Slavov Zizek and John McCain slam the same film, you’ve got something interesting. Depending on who you talk to, Zero Dark Thirty is either an indictment of America’s war on terror or pro-torture propaganda. The reality is far more murky: a look at horrific acts done for (what on an individual level are) altruistic purposes.

Tracing the decade-long search for Osama Bin Laden, Zero Dark Thirty is unflinching in depicting how “we” won. Director Kathryn Bigelow is known for her war scenes, and the final raid, replicated largely through night-vision goggles, comes across like a video game.

There’s a depersonalisation to the killings — an excitement and blood-lust, too, reflected in the ‘us v them’ mentality that allows for continued drone strikes. Modern warfare separates man from the killing machine, but overall, we focus on Maya (Jessica Chastain), a CIA intelligence worker whose life is swallowed by her job, who writer Mark Boal based off a composite of people.

It’s Zero Dark Thirty‘s final scene that offers a compass to its makers’ worldview. Maya’s instant elation then deflation after seems to suggest a search for a new enemy.

Her (2013)

A man falls in love with his phone: rather than a Leunig cartoon bought to life, Her is Spike Jonze’s best film. Set in the distance future, Theodore (Joaquin Phoenix) downloads a new iOS, an AI who names herself Samantha (Scarlett Johansson). Both are learning to be human, with Theo in the final stages of a divorce; without any expectations or well-trod paths for the two to go down, an intimacy grows without barriers.

Jonze’s future LA was half shot in Shanghai, and characters are dressed in Apple-commercial hues of bright, Uniqlo-esque pastels.

The director’s ad work is in his favour here, creating a misleadingly warm-coloured world that’s too streamlined to be anything other than cold. ‘Humanity’ is upside-down, as Samantha outgrows Theo’s understanding of emotional depth: it’s a tragedy of heteronormative romance, where true connection’s stifled by our expectations of monogamous, nuclear love.

Johansson took over Samantha’s role in post-production, thank God: her husky voice adds a sensuality to the iOS, as if she is continually experiencing new, strange sensations. And she is. Sensations that Her depicts in absence, showing dust specks float through the air, challenging us to imagine a world beyond atomic restrictions. Hopeful, optimistic, romantic.

Under The Skin (2013)

As in Her, Scarlett Johannson plays an all-powerful being in Under The Skin; both are desperately trying to become human. We meet her unnamed character stealing clothes from a dead woman; for the rest of Under The Skin, Johannson drives around Glasgow, ensnaring men under the promise of sex.

Under The Skin is both otherworldly and mundane, due to director Jonathan Glazer’s choice to cast mostly non-actors. Johannson would drive through town and pick them up in-character, with cameras hidden — only later would they be advised they’re in a film, and choose to go forward or not.

Their vulnerability in the scenes against Johannson’s mighty star-power only furthers the sense of helplessness, as does the brutal bleakness of Glasgow in winter. For a film filled with murder, the violence is minimal: the ‘sex’ scenes take place in a tar-black landscape, the men stripping and sinking into the earth below as they walk towards Johannson. The unnerving ritual is unclear in purpose, but Johannson’s character soon becomes empathetic, and seems to fight against own dark depths.

The score, by Mica Levi, is stunning, an eerie-off attempt to circle around each human experience Johannson’s character goes through for the first time, from eating to awkwardness. The stand-out is 5-minute epic ‘Love’, led by searching, lonely synths.

Frances Ha (2013)

The brightest of the decade’s ‘mumblecore’ movies, Frances Ha is pushed to the top of the pile by its sharp dialogue and a wonderful, career-defining performance by Greta Gertwig. Co-written by Gertwig and director/partner Noam Baumbach, Frances Ha doesn’t treat Frances, its 27-year-old crisis-having Brooklynite protagonist, as a manic dream pixie girl: Gertwig and her co-stars (including Adam Driver) all give their characters a lived-in feel, their quirks never overplayed.

What begins as a quirky friendship film becomes more as Francis continually stumbles from A to B, and struggles to pay rent. A gentle late-20s bildungsroman that is never afraid to laugh at Frances’ ennui; its ridiculousness doesn’t make it any less valid. It’s beautiful, too, with Baumbach’s decision to film in black-and-white allowing him to play with light in dazzling, understated ways.

Girlhood (2014)

Girlhood director and writer Céline Sciamma wanted to make a film about poor black French teenagers, inspired by groups she saw lazing around Paris. In some ways, it’s ultra traditional: we follow Marieme (Karidja Touré), who joins a group of girls and undergoes a transformation from meek to hardened, copying their style and joining their petty crimes.

There’s internal conflict, but there’s also great connection: the film’s best scene is in a hotel the girls rent with stolen money. Under blue light, they dance and lip sync to ‘Diamonds’ by Rihanna; they shine bright, together. Girlhood isn’t perfect — it’s not even Sciamma’s best film of the decade (that goes to Portrait Of A Lady On Fire). But this scene is one of the most joyous of the 2010s, capturing how freeing teenage friendships can be, if only for a moment.

The Duke Of Burgundy (2014)

As far as we’re aware, The Duke Of Burgundy is the only BDSM-love story film to come out in the middle of the decade.

Lesbian lepidopterists Evelyn and Cynthia engage in a strict dom-sub relationship within the confines of their own home, though it’s clear that one is more invested than the other. Erotic, funny, and bizarre — director Peter Strickland’s speciality — The Duke Of Burgundy is a beautifully lit, sensitive look at love’s compromises, whatever they may be. Also features the best use of mannequins since Seinfeld.

The Tribe (2014)

It’s hard to recommend The Tribe. Incredibly brutal, Myroslav Slaboshpytskiy’s film is set in a boarding school for deaf Ukrainian teenagers. A new boarder, Sergey, finds himself in the deep web of crime and violence that underpins the school.

Shot in Ukranian sign language with no subtitles, the film carries relies on tone alone to convey its conversations — sound, as to be expected, is used masterfully. We largely have to fill in the gaps of the film’s dialogue and plot: the refusal to translate only heightens the helplessness.

The Tribe is an upsetting, strange watch, one where tragedy suddenly snaps into place seconds before it occurs, mirroring the deep dread of the boarder’s lives.

Mad Max: Fury Road (2015)

Given its topped many of the internet’s best-of lists, we don’t really need to tell you Max Max: Fury Road is masterful.

In a decade where reboots and remakes reigned, Fury Road reinvents the wheel — Max is put aside in this film to centre the survival of Furiosa (Charlize Theron), the leader of a harem of fertile women who flee from their imprisoner.

Director George Miller swaps them out so well that the average audience might’ve not realised they were watching an eco-feminist action thriller. The waste and bile of Mel Gibson is well-and-truly washed clean from Mad Max; it presents a better, far more interesting film — a western where the women try to create a new world in the apocalypse.

Tangerine (2015)

Yes, Sean Baker filmed Tangerine on the iPhone 5s, and bloody hell, that’s impressive. The sun-flares alone are unbelievable, casting a burnt red over LA on Christmas Eve — it’s beautiful to match, painting the city by the harsh light it deserves.

Set around concrete strips and depressing strip malls, Tangerine follows trans sex worker Sin-Dee Rella (Kitana Kiki Rodriguez). Fresh out of prison, she goes on a day-long mission to find her boyfriend and pimp after finding out he’s cheated on her, with frenemy Alexandra (Mya Taylor) by her side.

While there’s a lot of slapstick comedy in there, Tangerine‘s best when it shows how these women support each other in a cruel climate. Resonates with warmth.

The Lobster (2015)

Yorgos Lanthimos’ loves a complicated, dark-comedy morality film (The Killing Of A Sacred Deer, The Favourite), but the surreal world in The Lobster is something else.

In The Lobster, single adults are given 45 days in a government-controlled hotel to find a partner, lest they be transformed into the animal of their choice.

David (Colin Firth) chooses the lobster for their tough shell, but is determined to find a mate under the draconian dating system underway, cheating and lying to find a woman to make a wife. A woman (Rachel Weisz) could be it.

Connections are made over fickle similarities in a clinical environment; love becomes a saving grace, but not as we know it. Rebels linger in the forest, refusing to play by society’s rules — but they turn out to be equally oppressive. A dark, moving parody of our laws and expectations around relationships, revealed to be as absurd as we already know them to be.

Personal Shopper (2016)

If anyone is still out here calling Kristen Stewart a terrible actress, show them Personal Shopper.

Most of the film, directed by Olivier Assayas, has her on screen, and she’s most often acting alongside a screen — staring at a phone, a computer, dreading messages, begging for them to come. Maureen (Stewart) is a personal shopper for a supermodel in Paris who recently lost her twin brother; believing herself to be a medium, she tries to contact him.

Maureen’s grief spools out across her listless life, and messages from a strange source push her in dangerous directions, desperate for a conversation. She, of course, is being haunted. The way Assayas films her phone and Macbook screens (always boxes in boxes, with so much anxiety contained in the bubbles of a message being typed from an unknown source) suggest we’re never severed. Always contactable, never by those who we want. Mysterious, eerie, unsatisfying: like Maureen, we’re left needing more.

Moonlight (2016)

Moonlight is a marvel. A life epic, we follow Miami kid Chiron across his life — played by three actors — as the tides of oppression against his class, race and sexuality dictate his life and constrict his core.

Director Barry Jenkins always offers light in what could be an incredibly depressing film — Chiron is granted moments of release, whether on the quiet night shore, or in reconciliation. Moonlight is painterly; its colours go from vibrant to cloudy, resembling the chop-and-screw music of Miami, hard-hitting and soft all at once.

The film tackles internalised homophobia, class shame and racism with a deft hand — like Chiron, it floats, when it could sink.

Certain Women (2016)

Certain Women is a quiet film: only one scene has a score, and its three storylines never labour their emotions. Adapted from stories by Maile Meloy, director/writer Kelly Reichardt shifted them to Montana — the backdrop is cold and understated, linking these (loosely related) stories by tone and colour, rather than meaning.

Laura Dern plays a lawyer in an affair with a married man; Michelle Williams is ignored by her husband, and convinces a man to part with his sandstone for next to no money; Kristen Stewart is a law student who travels eight hours by car to teach a rural class.

But for all the stars, it’s Lily Gladstone who sits at the heart of Certain Women, playing a lonely ranch-hand who falls in love with Stewart’s character.

Their connection is strange and misplaced; it is cold and warm, but it is enough. This seems to be the best these characters can ask for.

A Ghost Story (2017)

Casey Affleck is mostly under a white sheet in this film — director David Lowery swears he played the bed-sheet ghost that meekly moves through A Ghost Story.

We begin with him alive, living in a semi-domestic bliss with his wife (Rooney Mara); after he’s killed in a car accident, he returns home in the morgue’s sheet. Mara’s grief is heart-breaking — one scene involving her eating a pecan pie is laugh-out loud sad — but it fades.

The ghost meets other undead, who wait for people they can no longer remember — soon, that will be him, as centuries move on and the landscape changes. Grief remains, stupidly stubborn in a child’s costume.

Call Me By Your Name (2017)

There’s a lot to love about Call Me By Your Name: its sensuality, for one. While there’s criticism for Luca Guadagnino fading-to-black instead of showing the sex scenes between Elio (Timothée Chalamet) and Oliver (Armie Hammer), the film radiates in tension and release.

Their summer fling has an expiration from the beginning, but they do their best to possess each other — as if they are vessels to be emptied, to fill themselves with each other’s essence for life. The key scene is Elio’s infrared dream, where his memories of their time together are stretched out: they wander over monuments instead of past them, as he imagines the possibilities they’ll never have.

Chalamet’s performance, electric skinned to every emotion, captures the feeling of first obsession, and Gauadagnino’s sinewy world intoxicated audiences under the same spell.

Lady Bird (2017)

There’s so much to love about Lady Bird — the ’00s of it all, Timothée Chalamet as an intellectual bad boy reading Howard Zinn, Lucas Hedges being awkward and endearing, the Justin Timberlake scene — but ultimately, this coming-of-age is about Lady Bird (Saoirse Ronan) and her mother (Laurie Metcalf).

The beats of their relationship of loving someone you don’t particularly like — resenting the way you restrict one another, respectively class status and lost youth — are painfully played out by the actresses, who wrap affection and anger into the same lines. Greta Gertwig’s first film behind the camera brims with her energy; it is kind-hearted, goofy and incredibly empathetic, directed with a deep love for all characters.

Get Out (2017)

As social phenomenon alone, Get Out deserves to be on this list. Comedian Jordan Peele’s foray into directing/writing didn’t just capture America’s racial landscape, it provided the language to define it: the ‘sunken place’ has become as ubiquitous as ‘Uncle Tom’, and lines like “I would have voted for Obama a third time if I could” have become stand-ins for how racism hides behind liberal language.

It’s also an excellent horror film, one which twists and turns in ways that, in retrospect, shouldn’t be surprising — sure, it’s fantastical, but the writing’s on the wall from the get go.

Daniel Kaluuya’s performance is stunning in the lead, while the entire horrific family around him are absolutely terrifying — particularly his girlfriend, played by Girls‘ Alison Williams in a perfect casting move.

One thing that’s oft-forgetten is how funny Get Out is. It’s a blend of horror and Black black comedy, playing with Black character tropes like the dopey best friend in mercifully tension-releasing ways.

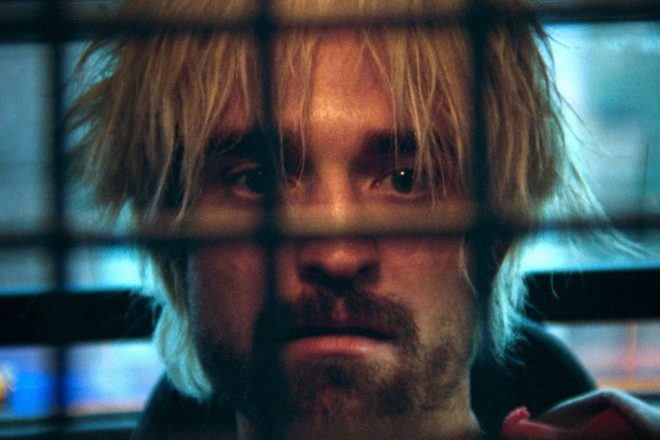

Good Time (2017)

It’s hard to talk about Good Time without sounding like an over-hyped teenage boy. The music! The story! It’s all so wild, man.

Director duo the Safdie brothers stack anxiety upon anxiety in this crime-thriller, which follows bank robber Connie (Robert Pattinson, somehow looking ugly) as he tries to break his mentally handicapped brother (Benny Safdie) out of hospital so they can live free. Nothing goes right.

The film builds tension and frustration that it never quite lets loose at the failing US healthcare system that pushed Connie to rash decisions. At film’s end, you’re allowed to breathe; but what’s been holding you back?

BPM (2017)

BPM director Robin Campillo drew from his own experiences within AIDS activist group ACT UP for this film, which focuses on the flame as much as the flicker of ’90s activists.

We follow ACT UP’s dramatic public protests and in-fighting in Paris first, before the film shifts to the stories of several key members’ own battle with AIDS.

The heart of BPM, as per its title, is a dance-floor sequence where they celebrate a minor win — the camerawork gets granular, as bodies sweating in ecstacy are blurred in favour of the dust particles in the air. It shifts into an image of the virus in a bloodstream — but it doubles as a mirroring of these activists, abandoned by the world, but creating a pulsating community that swirls with sadness, joy and support.

Phantom Thread (2017)

Paul Thomas Anderson grabs Daniel Day-Lewis for his (supposed) last-ever film role and takes him on a lecherous, loving ride through British fashion houses and BDSM by another name.

Phantom Thread follows Alma (Vicky Krieps), a waitress who finds herself the muse of Reynolds Woodcock (Day-Lewis), the lead designer of one of ’50s London’s last haute couture houses. Controlling and demanding, he and sister/house manager Cryil (Lesley Manville) are cold people to live with, but Alma refuses to be subservient. Visually stunning and strange, PTA delivers one of his finest films, a twisted love story threaded together by Krieps, whose performance more than matches Day-Lewis.

Sweet Country (2017)

Sweet Country is Warwick Thorton’s first major film since Samson and Delilah. With it, he establishes himself as one of Australia’s most integral contemporary directors.

Based off a true story of an Indigenous man shooting an ANZAC veteran in 1929, Sweet Country sees Sam (Hamilton Morris) on the run through the Northern Territory, with an Indigenous tracker forced to lead authorities to him.

Unflinching and unwilling to cede on the brutal horrors white Australia has inflicted on Indigenous people, Sweet Country is a neo-Western that spins the outlaw into its rightful figure: an Indigenous man who uses his knowledge of the harsh country against his foes. The territory’s harsh climate is rendered in vibrant, lively colours, as if Thorton is re-writing our films’ colonial gaze that paints it as a mysterious, dangerous land. For some, sure, but not Sweet Country, which comes from a different, usually erased perspective.

The Rider (2017)

Before she was poached to direct Marvel’s The Eternals, Chloé Zhao spent time in the Sioux reservations of South Dakota.

The Rider was built around the people she found there. Professional horse rider Brady Jandreau, who was forced to give up his passion after suffering a severe head injury, plays a fictionalised version of himself — surrounded by his family and friends, struggling to find his purpose.

Quiet, reflective and brimming with real agony, The Rider shows a generation of men who are raised to idolise an emotionally truncated masculine archetype: the cowboy.

There are no mass releases of emotion in the film, just glimpses of what’s underneath. Still, a scene where Brady trains a horse in real time shows a genuine connection to riding beyond bravado. It approaches a spiritualism, something the Sioux people have struggled to keep alive.

Burning (2018)

Based loosely off a Haruki Murakami short story, Burning is built around mystery.

Jong-su (Jeon Jong-seo) begins a relationship of sorts with childhood friend Hae-Mi (Yoo Ah-in), who soon becomes infatuated with the wealthy Ben (Steven Yeun) — the film burns with anger over class arrogance and its divide. Running for two and a half hours, Lee Chang-dong’s film is a slow-burn, a wonderful character study that lets each moment sink in with a sense of inevitability.

Jong-su cannot compete with Ben, who approaches a Patrick Bateman level of sheen — Yeun is unnerving in the role, always with-holding what lurks underneath.

As Jong-su loses Hae-Mi to Ben, he is obsessed with getting her back, but the mystery lends way to something bigger: a sense of helplessness in a society geared for him to lose, and Ben to win. Burning’s cinematography lays everything out — menacing, cold, oddly unsettling, even in moments of absolute quiet.

Eighth Grade (2018)

Never has teenage social anxiety and self-esteem been so potent: as Kayla, Elsie Fisher will make you squirm in pain with each facial expression. Eighth Grade is a claustrophobic film, following a 14-year–old girl struggle to make friends: she was voted “most quiet” by her year, and is determined to change that.

Burnham cast Fisher as she was the only actress who auditioned who felt truly shy, rather than a confident kid playing it. Critics love Eighth Grade‘s ‘interrogation’ of how social media fuels anxiety, but it’s only ever treated as a symptom rather than a source, settling on a less moralistic message about kids on the internet.

Fisher’s performance is so vulnerable that you feel the weight of an awkward conversation or stumbling over words, transporting you back to the worst of your teenage years.

First Reformed (2018)

Reckoning with the psychological impact of our changing globe, First Reformed focuses on Reverend Ernst Toller (Ethan Hawke), a pastor undergoing a crisis of faith.

Toller’s parish is dwindling due to a mega-church nearby, but it’s the church’s failure to act on climate change that throws him into a spiral. As he reckons with a corrupt systyem led more by corporate sponsorship than scripture, Toller tries to do what he can to change the world — a futile sacrifice, though it is all he can do.

First Reformed is the climate crisis film of the decade: deeply considered, stirring, fuming with anger, quietly hopeful of a better world. Of course, no where near enough people paid attention.

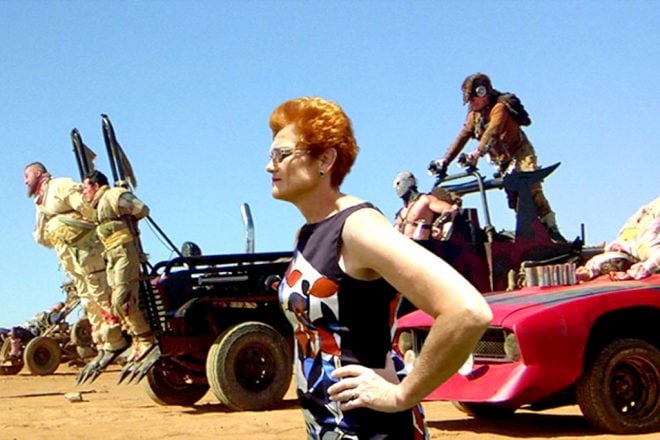

Terror Nullius (2018)

Art duo Soda_Jerk’s Terror Nullius made waves for being denounced by the same foundation that gave it a $100,000 grant to make the film, calling it a “very controversial piece of art”. It is: glorious, too.

Comprised of cuts from classic (and not-so classic) Australian film, pop-culture and television, Terror Nullius re-writes our cultural history.

Mel Gibson’s Mad Max is beaten by Kath and Kim and ridden over by Nicole Kidman in BMX Bandits, after they hear the actor’s abusive phone call to his then-girlfriend.

Pauline Hanson is part of an apocalyptic, racist gang with Housos characters. The Babadook is gay, and enjoys spinning around to Kylie Minogue. Skippy encounters bush doofers dancing to Itch-E and Scratch-E’s ‘Sweetness And Light’.

Jumbling together political speeches and pop-culture images of Australia, Terror Nullius sketches a blueprint for an alternative Australia — one free of discrimination and colonial violence — with great poignancy and humour.

Midsommar (2019)

In two years, Ari Aster has established himself as one of horror’s most interesting contemporary auteurs. Both Hereditary and Midsommar are so successful for their affecting, utterly choking cloud of dread — one even Sweden’s relentless Summer sunshine can’t pierce.

Midsommar‘s heroine is Dani (Florence Pugh), who tags along on her boyfriend’s ‘academic’ boys trip to a Swedish ritual that occurs once every 90 years. An awful family tragedy occurs immediately in the film; her boyfriend, ready to break up with her, instead invites her along.

The ‘ritual’ is something of a bloodbath, but the true terror is Dani’s dissolving relationship with her boyfriend (Jack Reynor), and his continual disavowal of her feelings. Few things make your skin crawl as an early scene where he gaslights her into apologising for ‘overreacting’ to something she has every right to dump him for.

Dani’s grief is bottled up, but Sweden is the place it’s finally heard and exorcised. A menacing, incredibly rewarding break-up film — albeit with a lot more ritual sacrifices and screaming than Marriage Story.

Parasite (2019)

If someone spoils the twist of Parasite, they’re a bad person.

All you need to know about Bong Joon-ho’s (Okja, Snowpiercer) ultra-dark comedy is that it focuses on two Korean families: one rich, one poor. When the latter’s son gets an opportunity to work as a tutor for the wealthy family’s daughter, the poor family hatch a plan to replace all the servants in the house by whatever means necessary.

Parasite balks at the myth of bootstrap capitalism, and has a lot of fun with its fury. In June, Joon-ho told Junkee there are “no devils” in the film: Parasite’s name comes from neither family, but the way we are all morally compromised in order to not just succeed, but survive.

Incredibly funny and sharp, it’s led by spectacular performances. With each twist and added layer, we are led to ask how the hidden depths of pain and exploitation that hold up the world’s powerful.

The Nightingale (2019)

The Nightingale is absolutely brutal: as well-reported, its first fifteen minutes feature a sexual assault so horrific that hordes of people walked from its debut at Sydney Film Festival. But a film about colonial Tasmania needs to disturb, otherwise it’s not about colonial Tasmania, a site of Indigenous genocide

Directed by The Babadook‘s Jennifer Kent, The Nightingale is also a film of internal trauma. When Irish convict Clare (Aisling Franciosi) is attacked by a British officer and left with nothing, she vows revenge. Enlisting a local Indigenous tracker, Billy (Baykali Ganambarr), Clare follows the officer through the Tasmanian bush.

Only brutality follows, as Billy and Clare head towards a revenge without any possibility for reparations; everything is already lost. The film finds similarities in their oppression, but Indigenous dispossession and mass-murder is never equated to convict treatment: the link is in their mutual enemy, though the power imbalance is always present. The Nightingale isn’t about overcoming racism or Clare losing her own prejudices — it is a cry of defiance from voices long silenced.

Varda by Agnès (2019)

With Agnes Varda’s passing this March, we’ve lost a titan: an endlessly curious woman who created an exceptionally large body of work with a playful joy, while never treating anything as too light, creating profound meaning from the world’s quirks.

Of course, her last film is a stunning farewell. Varda by Agnès sees the director reflect on her six-decade career with fondness and a deep creativity, even in her 90s. Varda once said, “I don’t want to show things, but to give people the desire to see”.

A joy to watch from start-to-finish, Varda by Agnès is a testament to a singular director and her gift, filled with more love for the world than a love-heart shaped potato.

Jared Richards is a staff writer at Junkee, and co-host in Sleepless In Sydney on FBi Radio. Find him on Twitter.