The 20 Best Films Of 2019, From ‘Hustlers’ To ‘Parasite’

We're pretty sure Scorsese would approve ('The Irishman' exclusion, uh, excluded).

The most ambitious crossover in history snapped its fingers, and broke the box office: like it or not, Avengers: Endgame is the highest-grossing film of all-time (before inflation, that is).

Ambition implies the risk of failure, but Avengers was eleven years of hype in the making. Almost every box-office hit this year bellied itself off existing IP: it’s low-risk, high-reward, even with the occasional mis-fire, like Charlie’s Angels.

Of Australia’s top 20 grossing films this year, four had no ties to a cinematic/TV franchise (Bohemian Rhapsody, Green Book, Once Upon…, Yesterday). That’s not to say 2019 is anything new, though it’s fair to say the way we talked about it was.

Critics and creatives feared an end of cinema bought down by the twin powers of streaming and superhero films, best articulated by David Ehrlich in his viral review of Joker.

“The next Lost in Translation will be about Black Widow and Howard Stark spending a weekend together at a Sokovia hotel,” he wrote. “The next Carol will be an achingly beautiful period drama about young Valkyrie falling in love with a blonde woman she meets in an Asgardian department store.”

Meanwhile, greats like Scorsese said superhero movies were ‘entertainment, not cinema’, going against the poptivist mould of critical thought that’s characterised the past decade. He’d later clarify the off-hand remark in a NYT op-ed.

“Many of the elements that define cinema as I know it are there in Marvel pictures,” he wrote. “What’s not there is revelation, mystery or genuine emotional danger. Nothing is at risk. The pictures are made to satisfy a specific set of demands, and they are designed as variations on a finite number of themes.”

This only further angered a pro-MCU fanbase, and created some ridiculous Twitter-thread comparisons of The Irishman to Black Panther and Avengers. But Scorsese’s comments only echo the sentiment of most memes: ‘really, another The Lion King? Toy Story 4? Aladdin? Spiderman, again? — wasn’t Avengers just two months ago?’.

But for every complaint about Hollywood running out of ideas, we didn’t care when it came down to it. Still, if you want the (admittedly wanky) revelation Scorsese wrote of, here are 20 films we were shaken by this year.

Keep in mind, so many Oscar-buzzworthy films haven’t made it to Australian shores, even in screenings. For these reasons, we can’t discount the likes of Uncut Gems, Honey Boy, And Then We Danced, and, of course, Cats. Find the 35 best films of the decade here.

The Beach Bum

Spring Breakers, Harmony Korine’s havoc-filled EDM-bikini heist film, came out in 2013. In the six years since, it’s been gif’d to hell and back — an all-too intoxicating mix of teenage hedonism with pastel colours, in a sharp meta-casting of Disney stars as the good-girls-gone-bad (essentially what Vanessa Hudgens and Selena Gomez were doing by signing up to the film).

Since then, the enfant terrible director has grown up — well, he’s older, at least.

The Beach Bum ages up its protagonist, too. Instead of teens, we follow around Moondog (Matthew McConaughey), a fucked-up Floridian poet who is incredibly acclaimed, always high and astronomically rich, thanks to his wife, actress Minnie (Isla Fisher). He’s not writing much, but his poetry is his life, man.

We watch him fuck around with Snoop Dog, Martin Lawrence and Zac Efron, whose hairstyle suggests he lost a fight with a sandwich grill.

It’s dumb as hell, but never lets Moondog completely off the hook. We see the pain he causes, but rather than blow it all up for a denouement (ahem, Ricki And The Flash), we stay focused on the fireworks. It’s only after the party that the hangover kicks in.

The Farewell

Director Lulu Wang wrote The Farewell about her own family returning to China from across the globe to say goodbye to their dying matriarch, who had absolutely no idea she only has months to live.

As Billie (Awkwafina, in a star-making role) struggles around the ethics of what her family has decided is best, she tries to bask in her last moments with Nai Nai, her grandmother, under the guise of a hastily thrown together wedding for her cousin.

Guilt pervades The Farewell, as generational differences, geographical distance and at-odds metrics for a successful life swirl. Growing up in the US, Billie’s philosophically opposed to the plan, while aware her feelings are far from the most important.

Similarly, Billie may be our anchor, but we sit with the pains of each character, all the while laughing at the ridiculous agony of any family affair. An incredible tenderness and empathy guides The Farewell, without over-saturating it in the process.

The Final Quarter / The Australian Dream

This year, we received two documentaries about the extortionate racism that prematurely ended Adam Goodes AFL career. Both are worth a watch, each providing distinctly different takeaways about Australia’s inherent racism, and what must be done to address it.

The Final Quarter came first, a blistering 75 minutes compiled entirely of archival footage. Director Ian Darling uses match-day footage, news broadcasts, panel show snippets, clips from press conferences and talk-back radio segments to tell a clear, inarguable narrative: Australia’s media dog-whistled for two years to break down Goodes.

And they succeeded, which The Australian Dream dives into. By interviewing Goodes and following him in the aftermath of standing down from the Sydney Swans, the film provides a heartbreaking insight into what we all knew was true — years of abuse took its toll on Goodes.

But the film is far from narrow in its scope. Written by Stan Grant, The Australian Dream takes its name from a speech he gave in 2015, in which he says that when Indigenous people heard the booing of Goodes, they heard “the howl of the Australian dream and it said to us again, you’re not welcome”.

As Grant takes over in the film’s end third to tell his own story, it’s clear that The Australian Dream is hammering home a point about our country’s racism. It may be less subtle than The Final Quarter, but the reaction to that film — the way it reignited a debate — shows that we still need things spelled out.

Gloria Bell

Sebastián Lelio has been behind some of the most-talked about queer films of the past few years, A Fantastic Woman and Disobedience, which yes, is that movie where the two Rachels spit into each other mouths.

Gloria Bell, an English language remake of Leilo’s own 2013 film Gloria, is not queer. But like Fantastic Woman or Disobedience, it is a film of emotional release and selfhood achieved, if only for stolen moments.

Julianne Moore plays Gloria, a divorcée we meet at a bar, working her way through a crowd to go dance alone. The film sees her navigate her shitty job, shitty children (Michael Cera one of them), and shitty men. She stands on the sidelines, then, with great effort, wiggles her way into the centre. Then she dances.

And the perfect song was recorded decades ago, waiting for the final scene. G-g-g-gloria! Gloria!

Her Smell

Her Smell is messy. Split into four scenes, each as geographically and time-confining as a play, Her Smell spans decades in the life of Becky Something (Elisabeth Moss), the drug-addled lead of a riot-grrrl-esque band.

It is clear, from the beginning, that the band are running on borrowed time. Becky is violent, uncommunicative, and difficult, but her bandmates and label rely on her, as does her ex-husband, who she shares an infant daughter with.

Incredibly claustrophobic and led by an erratic, unhinged Moss, Her Smell is a hard watch. Where Becky might feel like a joke in another’s hands, Moss pulls off the character’s desperate swings and unpredictable energy. With the camera constantly tracking her every move, it as if Becky controls the film rather than director Alex Ross Perry.

And maybe she does. Moss’s performance is award-deserving. It transforms a film about another fucked-up rock star into something bigger: the struggle to be a better person, smells and all.

Hustlers

Hustlers didn’t have to be good: its cast alone would have made it worth a watch. Based off a viral The Cut article from 2015 about a group of New York strippers drugging rich men and over-charging their cards, Hustlers has the energy of the heist movie Ocean’s 8 should have been, without the pandering need to create Feminist Moments.

Set around the GFC, Hustlers centres how trickle-down economics really works — ie., it doesn’t.

Worse of all is knowing this Robin Hood act can only go on for so long: it’s easy to savour the first third of the film, where the likes of Constance Wu, Cardi B, Keke Palmer and J-Lo fly high. There’s fun and fury in the rise and fall: this is a film about women arming themselves against a world that is determined to pull them down, even as those who created the GFC continue to get off free.

At one time, Martin Scorsese was attached to direct, and we imagine that being a much colder film. Lorene Scafaria (who also wrote the screenplay) clearly has a lot of empathy for these (real) women, as she, the film and we should: watching, we know the bubble will burst, but we desperately don’t want it to. Thankfully, the film also treats stripping as a hustle no cleaner or dirtier than an office job — well, if anything, maybe cleaner. It’s hard to watch J-Lo’s pole-dance routine to Fiona Apple’s ‘Criminal’ and not be born again.

While we’re on J-Lo, this is absolutely her film. As grand-planner Ramona, she exudes power whether in the most luxurious coat of all-time or shilling out her denim swimwear: it’s the case of a pop-culture figure finally getting the role and respect she deserves.

It’s an absolute joy to watch.

If Beale Street Could Talk

No-one can do extreme close-ups like Barry Jenkins: Moonlight made that clear, but his follow-up, an adaptation of a James Baldwin novel, took it even further.

There’s a painterly quality to the colours of these repeated close-ups of doomed lovers Fonny (Stephan James) and Tish (KiKi Layne) throughout the film; long after the specifics fade from your memory, that’s what you’ll remember. That and the brass-driven score, which aches and soars, all at once. Composer Nicholas Britell said he wanted it to sound like love.

Baldwin’s story about racism tearing apart young lovers is, of course, as relevant in 2019 as it was in 1974. Regina King won an Oscar for her role as Tish’s mother — she’s given the role of realising everything won’t work out because it should just as the audience does, but the resigned devastation in her performance can’t silence the score.

In Fabric

Sheila, a recently divorced bank teller living in London, buys a red dress in the Christmas sales: unfortunately for her, the dress is evil, and wants to kill anyone who wears it, even if that means breaking free of its wardrobe and flying through the air.

There are signs from the start that something is up. The shop-attendant speaks in bizarre, koan-like sentences, but Sheila (Marianne Jean-Baptiste) pays it no mind. Sales are weird enough, as is. We see Sheila go on sloppy dates, be berated in her job and by her adult, at-home son: we see the world has no time for her. But she has this dress, and the dress makes her feel drop dead gorgeous.

In Fabric is camp and stylish horror, equally laughable as it is scary. It might lose its way a little in the end third, but director Peter Strickland’s provided a pastiche of B-grade horror with an eye for A24 aesthetics unlike anything else that’s arrived this year. Beware the sales.

In My Blood It Runs

Australia is failing its young First Nations people, and documentary In My Blood It Runs details the unfairness that shapes our country. Director Maya Newell (Gayby Baby) spent three years filming Dujuan, a then 10-year-old boy and healer, living largely in Mparntwe (Alice Springs).

Despite his precocious intelligence, he struggles in school. The back-and-forth we see between his community, school and police are angering to watch. Scenes where well-meaning teachers completely miss the point in class spell it all out — the approach is all wrong.

The film was made in close connection with Dujuan’s families, acting as a kind of blueprint forward: Dujuan is the most endearing child, and the film’s environment fosters it. The world it documents doesn’t.

In My Blood It Runs will have a proper release next year, after screening across film festivals in 2019. It will make your blood boil.

Island Of The Hungry Ghosts

It is clear the horrors of Australia’s off-shore detention centres are not connecting with the masses. Gabrielle Brady’s debut feature documentary Island Of The Hungry Ghosts tries to connect the dots with something different, alternating between filming Christmas Island’s two most famous images: the (recently re-opened) detention centre, and the yearly migration of millions of red crabs from the forest to the ocean, effectively shutting down the island.

Without access to the detention centre, Brady instead follows Poh Lin Le, a trauma and torture counsellor who works with refugees who are only being continually tortured and traumatised. Red tape and a lack of communication continually get in the way; it’s clear even this small act of compassion is being wrestled out. Meanwhile, the crab’s migration is treated with awe and respect. A force of nature, they aren’t fought against — instead, they are built paths and brushed off roads to avoid cars.

The ongoing layers of trauma are given time, too. The film’s title is from a line given by one of the Island’s residents upon showing the unmarked graves of the Malay Chinese indentured servants and miners led there by British rule. We witness an offering ceremony from the Island’s residents, said to sate the hungry ghosts. Christmas Island is pictured as an eerie, lonely space the natural migration of the crabs sees the Island shut down and give way to nature, and we watch residents compassionately brush them out of the way on roads.

Island Of The Hungry Ghosts doesn’t provide a lot of political context. It is less concerned with facts than it is feeling, and that even if Australia isn’t paying attention now, we will be forever haunted by the horrors of our detention centres.

Knives Out

Whodunits, for the most part, have been relegated to TV this decade: a so-so Murder On The Orient Express remake came and went a few years back, but was dead on arrival. Knives Out, thankfully, pulses with energy. Written and directed by Rian Johnson, Star Wars director via Brick and Looper, two inventive takes on the detective and action genre, Knives Out is a sharp, playful and distinctly 2019 murder mystery.

On the morning after his 85th Birthday Party, successful mystery novelist Harlan Thrombey (Christopher Plummer) is found dead, assumedly having slit his own throat. All is not as it seems, of course, and the entire Thrombey family are under suspicion from Benoit Blanc, aka Daniel Craig with a delightful Southern accent. Our protagonist isn’t any of the ‘self-made’ Thrombeys, but caretaker Marta (Ana de Armas), with her outsider status letting us see the Thrombey’s merits and flaws, and how privilege affects our actions in life — while never getting too didactic.

Easily the ‘funnest’ film on our list, plus it features Jamie Lee Curtis in a pink power suit and Chris Evans in a beautiful white sweater.

Marriage Story

Scarlett Johansson, for all her faults, is an excellent actress, and Adam Driver has proven he can shift between blockbuster and indie-drama at ease. Put the two together (or, rather, tear them apart) with a tight script, and you’ve got a film ready to swallow your heart whole. Written and directed by Noah Baumbach, Marriage Story follows a couple as they try to consciously uncouple, before it becomes evident that the idealistic, painless divorce isn’t possible.

As actress Nicole (Johansson) moves back to LA from New York, where she and playwright Charlie (Driver) lived with their son, a custody battle breaks out, featuring Laura Dern as an LA lawyer who her Big Little Lies character would sink back a few wines with. Their respective heartbreaks and resentments look and feel different — rather than have us pick sides, Marriage Story sits with the sinking realisation that when we split, so too do the narratives, neither necessarily more right than the other.

Despite writing from personal experience, Baumbach is ultimately as empathetic to Nicole as he is Charlie. The film does the impossible job of creating one (divorce) story, equal comedy and tragedy, as break-ups often feel moment to moment.

Midsommar

In two years, Ari Aster has established himself as one of horror’s most interesting contemporary auteurs. Both Hereditary and Midsommar are so successful for their affecting, utterly choking cloud of dread — one even Sweden’s relentless Summer sunshine can’t pierce.

Midsommar‘s heroine is Dani (Florence Pugh), who tags along on her boyfriend’s ‘academic’ boys trip to a Swedish ritual that occurs once every 90 years. An awful family tragedy occurs immediately in the film; her boyfriend, ready to break up with her, instead invites her along.

The ‘ritual’ is something of a bloodbath, but the true terror is Dani’s dissolving relationship with her boyfriend (Jack Reynor), and his continual disavowal of her feelings. Few things make your skin crawl as an early scene where he gaslights her into apologising for ‘overreacting’ to something she has every right to dump him for.

Dani’s grief is bottled up, but Sweden is the place it’s finally heard and exorcised. A menacing, incredibly rewarding break-up film — albeit with a lot more ritual sacrifices and screaming than Marriage Story.

The Nightingale

The Nightingale is absolutely brutal: as well-reported, its first fifteen minutes feature a sexual assault so horrific that hordes of people walked from its debut at Sydney Film Festival. But a film about colonial Tasmania needs to disturb, otherwise it’s not about colonial Tasmania, a site of Indigenous genocide.

Directed by The Babadook‘s Jennifer Kent, The Nightingale is also a film of internal trauma. When Irish convict Clare (Aisling Franciosi) is attacked by a British officer and left with nothing, she vows revenge. Enlisting a local Indigenous tracker, Billy (Baykali Ganambarr), Clare follows the officer through the Tasmanian bush.

Only brutality follows, as Billy and Clare head towards a revenge without any possibility for reparations; everything is already lost. The film finds similarities in their oppression, but Indigenous dispossession and mass-murder is never equated to convict treatment: the link is in their mutual enemy, though the power imbalance is always present. The Nightingale isn’t about overcoming racism or Clare losing her own prejudices — it is a cry of defiance from voices long silenced.

Pain and Glory

Spanish auteur Pedro Almodóvar’s Pain and Glory is the perfect ‘late period’ film, a meditative and warm look at the cruelties and kindness of devoting your life to making art — often a more selfish than selfless act.

Director Salvador Mallo (Antonio Banderas) is in physical and artistic decline, and has been asked to present at a 30-year anniversary of one of his most acclaimed films. Pain And Glory sees him look back at his childhood and career, from his relationship to his mother (Penelopé Cruz), his queerness and heroin. Feelings and flaws resurface, regrets linger, and everything looks absolutely gorgeous.

Parasite

If someone spoils the twist of Parasite, they’re a bad person.

All you need to know about Bong Joon-ho’s (Okja, Snowpiercer) ultra-dark comedy is that it focuses on two Korean families: one rich, one poor. When the latter’s son gets an opportunity to work as a tutor for the wealthy family’s daughter, the poor family hatch a plan to replace all the servants in the house by whatever means necessary.

Parasite balks at the myth of bootstrap capitalism, and has a lot of fun with its fury. In June, Joon-ho told Junkee there are “no devils” in the film: Parasite’s name comes from neither family, but the way we are all morally compromised in order to not just succeed, but survive.

Incredibly funny and sharp, it’s led by spectacular performances. With each twist and added layer, we are led to ask how the hidden depths of pain and exploitation that hold up the world’s powerful.

The film of the year.

Portrait Of A Lady On Fire

You’ll no-doubt hear Portrait Of A Lady On Fire referred to as ‘the lesbian Call Me By Your Name‘, but it casts its own shadows over obsession.

Although it’s set in eighteenth century France, Portrait Of A Lady… is no queer tragedy. Painter Marianne (Noémie Merlant) arrives in Brittany to take a portrait of Héloïse (Adéle Haenel) for her fiancé, who she does not wish to wed. Unwilling to sit for the portrait, Héloïse must be painted in secret; Marianne befriends her to study her features, and the two fall for one another.

The closer the two get, the better the portrait capture’s Marianne’s essence, thereby ensuring the marriage. Unlike CMBYN, Portrait… is not about possession as it is about communication. Director Céline Sciamma fills the film with as many colours as Marianne does in her portrait: both their gazes are tender, rather than controlling.

The agony of their stolen hours singe both Marianne and Héloïse, but, at some point, they decide it is better to be burnt by desire.

Us

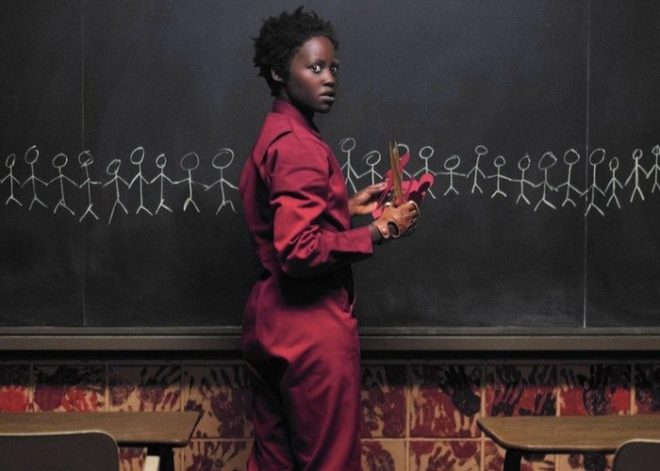

How do you follow up one of the decade’s sharpest social-horrors? Jordan Peele double-downs with Us, a terrifying look at social inequity and the way we shove one another down to stay on top.

Us is a simple premise: a family go on holiday, only to meet their deadly dopplegängers. Adelaide (Lupita Nyong’o) realises what’s happening, having had a traumatising encounter with her own twin as a child: both she and her ‘tethered’ version, Red, are the matriarchs of their families, and lead the way to survival.

Like Parasite, Us uses mirroring as social commentary — how we refuse to lower ourselves (economically, socially) to lift others up. Unlike Bong Joon-ho, Peele leans hard into horror. There’s a lot to scream about.

Vox Lux

Strange, confusing and divisive, Vox Lux‘s convoluted log-line — a child becomes a pop star after surviving a school shooting — doesn’t even begin to cover how much of a fever trip it is. Director Brady Corbett (Child Of A Leader) wanted to set Vox Lux, subtitled A Twenty-First Century Portrait, around acts of homeland terrorism.

In its first half, Celeste (Raffey Cassidy) barely survives being shot in the neck in a school shooting circa Columbine, and is soon swept up into a pop career after a song she writes with her sister becomes a mourning song for the anthem. We skip ahead at 9/11 to 2017, where Celeste is grown into a troubled star (Natalie Portman) on the eve of a comeback concert — the various actors (Jude Law, Stacy Martin) around her haven’t aged, and Cassidy plays her daughter.

Portman and Cassidy’s Celestes are completely different, as Corbett purposefully didn’t have them collaborate on the character: the second half of Vox Lux is so jarring it makes you wish we could stay in the first, even with all its traumas. That is likely the point: the worst is yet to come. Add in truly surreal pop by Sia — possibly some of the most phoned-in music of her career — a concert by Portman, an overwrought narration by Willem Dafoe and the equation of American violence with pop vapidity, and you’ve got a film that is at once infuriating and intoxicating.

It is broken, pretentious and brilliant; for better or worse, it is A Twenty-First Century Portrait.

Jared Richards is a staff writer at Junkee, and co-host of Sleepless In Sydney on FBi Radio. He is on Twitter.