Junk Explained: What Is The Momo Challenge, And Why Is It Everywhere?

The Momo Challenge taps into a long-standing fear: that parents cannot project their kids from not just the internet, but the world.

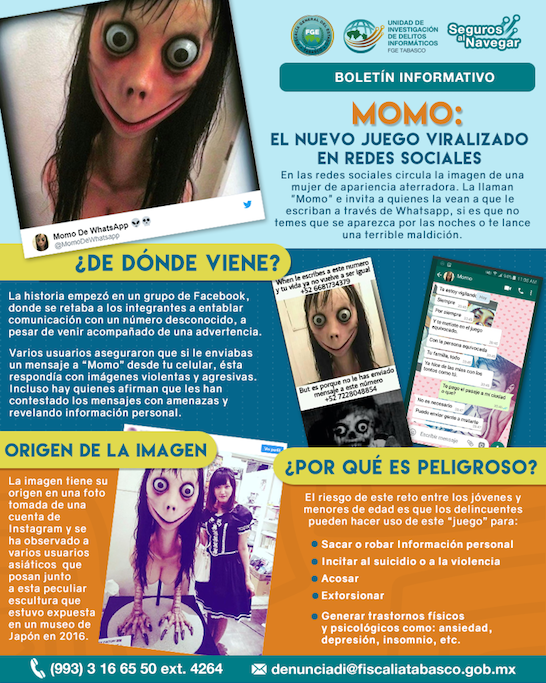

You’ve probably seen a not-so friendly and uncanny valley face floating around on social media. Her eyes bulge, and her face is stretched, and her greasy fringe needs some TLC (sorry!). Without context, she is vaguely creepy, almost lazily. Her name is Momo, and according to the internet, she wants your children dead.

— Content warning: this article discusses suicide and self-harm —

Momo has been around for a little while, but in the past week, media reports about the ‘Momo Challenge’ — a series of ways in which this image is used to taunt and coax children into committing acts of violence and self-harm lest Momo leap from the screen and into their lives — have gone viral.

The reports have, to say the least, been greatly exaggerated. The challenge is a hoax, but a potent one, cut from the same cloth as Slender Man and Tide Pods.

Momo taps into a long-standing fear: that the internet is a frontier which children venture further and further into, and that it is impossible to follow along or protect them. But how did we get here?

Who Is Momo?

Momo is art.

Literally: she’s a sculpture called ‘Mother Bird’ made by Keisuke Aiso from Link Factory, a Japanese special effects and film prop house. It was displayed in a Ginza gallery back in 2016 — pictures found their way onto Reddit’s r/creepy board about seven months ago, with people saying they were very, very freaked out by it.

“This was the first time something has legitimately fucked me up on this subreddit,” reads the top comment. “…I decided to look at it again after posting and I’m legitimately shaking and don’t feel safe. Good job at whoever made this abomination.”

The image is cropped too: here’s the full sculpture. According to Rolling Stone, Momo’s likely inspired by ubume, a Japanese folk story figure who died in childbirth and is known to haunt people.

Momo sculpture.

Eventually, the image wound its way into a creepypasta, a scary story which circulated online. The post/video/image will invite you to message Momo on WhattsApp, where you’ll be asked to share some personal details and be given a series of tasks, ranging from watching scary movies to self-harm and suicide.

It’s all very similar to Blue Whale, a ‘challenge’ which dates back to 2016 where anonymous administrators give challenges over 50 days which level up to suicide. None of the alleged resulting deaths can be 100 per cent confirmed to be linked to Blue Whale, though in 2016 21-year-old Russian Philipp Budeikin was arrested and charged for encouraging teenagers and children to commit suicide through the game.

But almost all of the charges were subsequently dropped, and the BBC believes the whole thing was a hoax for Budeikin to gain social media followers.

How Did It Begin?

Momo seems to pick up where Blue Whale left off, though it’s not clear where exactly it began — or by who. It does appear to have gained steam in Spanish-speaking countries first through, and last September, Mexican police released a statement warning the public about “El Momo”.

In addition to being coerced into self-harm, the police alleged children were being sent explicit and violent images, and threatened into sending pornographic images.

Mexican authorities released a warning about the ‘El Momo’ challenge last September.

Since then, English-language sites have reported on the Momo challenge, interviewing safety ‘experts’ and citing an unconfirmed story about a 12-year-old girl in Buenos Aires taking her own life last July.

In the past week, it’s been reported on extensively after the Northern Irish police made a Facebook status to warn parents about the challenge. In it, they allege the challenge is actually a way for hackers to gain personal info through intimidation and threats.

“One video of such interaction in America I’ve seen shows an ominous sounding voice recording being sent to a child telling them to take a knife to their own throat,” it reads. “Another threatens family if a ‘challenge’ is not completed. It’s chilling viewing. There are numerous variations and of course now imitators.”

Following this, a UK Primary School posted a status in which they warned parents of videos with Momo, saying “examples we have noticed in school include asking the children to turn the gas on or to find and take tablets”.

It’s awful stuff, but there’s little way to corroborate it — and tabloid reporting on it hasn’t helped. Bullying, extortion and threats obviously can and do occur online, but it’s not clear whether Momo was ever actually used by people to do so before the Momo challenge got media coverage.

But Why Has It Caught On?

Momo is a perfect confluence of clickbait: it’s sensational, confusing, ominous and yet vaguely believable. For good reason, too.

Two years ago, a long-form Medium article called “Something is wrong on the internet” went viral. Written by James Bridle, it examined the proliferation of cheaply-made and monetised YouTube videos for kids using bootleg-animations of Peppa Pig, Disney characters and more.

Some were innocuously creepy; some were incredibly disturbing and violent, waiting to be served by an algorithm to a toddler watching unsupervised. It’s unclear if they are churned out by trolls or a piece of coding morally corrupted; it does not matter. YouTube has since removed several of the offending channels, though it largely remains a frontier without police or protection.

In 2014, two 12-year-old girls in Winconsin repeatedly stabbed their friend, believing that creepypasta character Slender Man would hurt them if they did not. It does not matter that Slender Man isn’t real, because the horror behind it now is.

Momo has potential to create tragedy — and that potential terrifies parents, plaguing on their deepest fears about protecting their kids from not just the internet, but the world.

“Momo is what happens,” John Herrman for the NYT writes, “when the grown-ups start writing copypasta [which creepypasta is an iteration of] of their own, about their own biggest fears: what their kids are doing on the internet, and what the internet is doing to their kids.”

The real Momo no longer exists: its artist, Aiso, has confirmed to The Sun that the artwork has been destroyed, but only because it was rotting.

Still, Momo continues travelling far and fast thanks to the internet — though the moral panic behind it doesn’t rely on social media. Back in the ’80s, Dungeons & Dragons was linked to the suicide of a Virginia high school student, and the murder of a Missouri teenager. In the ’90s, violent video games were linked to the Columbine school shootings.

Time and time again, the links are tenuous at best, but the terror remains real.

If you’d like to talk about any issues with your mental health and options getting long-term help, you can reach Lifeline on 13 11 14, or beyondblue on 1300 22 4636.

Jared Richards is a staff writer at Junkee, and co-host of Sleepless In Sydney on FBi Radio. Follow him on Twitter.