What Happens To Our Sims When They Die?: On Virtual Grief And The Sims FreePlay

A new update to the massively popular title has left gamers furious.

Just last month, an update for The Sims FreePlay became available. If you’re not familiar with The Sims FreePlay, it’s a hugely successful mobile app based on The Sims, which is the biggest-selling PC game of all time.

Both The Sims and The Sims FreePlay are — for want of a more precise term — life simulators, where you guide your Sims through the trials of day-to-day human existence. Because things like ‘happiness’ and ’emotional wellbeing’ are vague and unquantifiable in reality, let alone a restricted virtual environment, most measures of success or failure in The Sims revolve around consumption and acquisition: for instance, one’s success in pursuits like making friends and attracting a mate are determined by how big your house is and how nice (read: expensive) your clothes are. It’s obviously pretty materialistic, but I can’t think how else a game might be expected to measure life progress, short of making your Sim read Das Kapital (and making your Sim read Das Kapital would probably be even less fun than making yourself read Das Kapital).

The game is similar to Second Life, but where Second Life, with its eye-level perspective, lends itself more towards the virtual role-play, The Sims, with its isometric, omniscient perspective, offers more of a ‘God’ aspect, allowing players to create and perfect families and social groups.

As part of the update, the game introduced something called ‘XP’, which I believe stands for ‘Xperience Pointz’. When a Sim accrued enough XP, they would be deemed ready for their next life stage: from infant to child, teen to young adult, and so on. Naturally, the final stage of this progression was the end-of-life stage, commonly known as ‘death’. In an attempt to see off the predictable backlash, the developers included a caveat: if it means that much to you, you can keep a Sim at the desired life stage by paying for the privilege.

What at first seemed to be an ambitious attempt at marketing death now appears to be more about monetising the previously taken-for-granted immortality of these beloved avatars, having already established the gamer’s dependency upon these avatars.

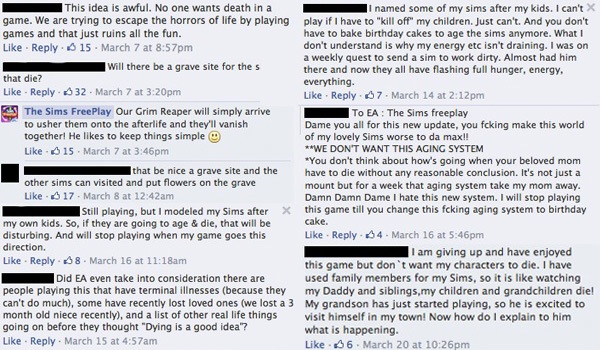

Needless to say, fans were pretty peeved at the prospect of seeing their Sims getting knocked off, particularly given that a lot of Sims are much more than just glorified Tamagotchi pets.

–

Virtual immortality

You see, immortality used to be pretty hard to achieve, unless you had a thousand-strong slave labour force, a quarry’s worth of stone, and a spare twenty years. These days, it’s pretty easy. We live our lives as cyborgs, with long, digital tendrils connecting our physical bodies to the hyperspatial realm. When our physical bodies expire, those tendrils will live for as long as the servers that store them (or until your Google Will swings into action). Our Facebook pages become personal Wailing Walls for those who outlast us, our blogs become records of a stream of consciousness, suddenly interrupted. Unwittingly, we spend our digital lives building our future memorials.

This is our new afterlife, but what of loved ones that we’ve lost? What of the virtual children, husbands, and wives that are created in The Sims FreePlay?

Plenty of Sims FreePlay-ers use the game to act out their own lives and those of their friends and family, building the spotless, acquisitive lives that reality has failed to afford them. Some have even created avatars that resemble their deceased grandparents. Those players were using the game less to pass the time and more to heal the psychic wounds visited upon them by reality, of dashed hopes, false promises and grief. They were, understandably, among those most upset by the introduction of death, which was seen as a corruption of their virtual refuge.

–

Grief in the hypersphere

As poignant as it is to use a game like The Sims FreePlay as a digital memorial, it’s dangerous to fix the mistakes of reality in a perfect hypersphere. Real people have cognisance and agency, whereas virtual representations of real people are just limp puppets doing your bidding in a creepy, onanistic digital theatre. While burrowing into oneself in the face of adverse circumstances is understandable, it’s not advisable to build an alternate reality while you’re in there.

Such a will to control and an unwillingness to engage with undesirable circumstances are present in comments all over The Sims FreePlay Facebook page, as is a distinct lack of self-awareness in accusing the game of ‘playing God’ with beloved characters.

“To EA: Dame you all for this new update, you fcking make this world of my lovely Sims worse to da max!!”, and so on.

The irony of this accusation is not insignificant, given that the whole ‘playing God’ thing is precisely what many gamers cherish most about the game, even if few would admit as much.

–

The economics of addiction

Monetising mobile games is a tricky business, though. Some developers use in-game advertising. Some developers offer a free basic product, and charge for upgrades and deluxe editions. Few, though, have the correct platform to pull the consumer into an intense bond — whether emotional, habitual or physical — with the product, and then force the consumer to place a value on that bond. The Sims FreePlay has such a platform, and they are currently exploring how far that bond can be stretched. Both drug dealers and supermarket chains understand this principle as a form of ‘inelastic demand’, in which variations in terms of quality and price fail to affect demand for a product.

Stringer Bell probably explained it best:

So, good business? Yes. A bit of a jerk move? Undoubtedly, yes.

But while The Sims FreePlay’s approach is a little manipulative, it’d be naive for gamers to think that they would be able to enjoy such a sophisticated game for free, forever. That’s the thing about free shit: there’s always a cost, but it’s not always apparent what that cost is, and how that cost might be extracted. Furthermore, the less obvious it is, the more nervous you should get. Sims FreePlay-ers, and particularly those who adapt the game to their own emotional needs, have just found this out.

–

Edward Sharp-Paul is a writer from Melbourne. His words can be found at FasterLouder, Mess+Noise, Beat and The Brag, or on Twitter at @e_sharppaul.