That Time I Accidentally Changed Hip Hop History

This is the story of how I may have fed the entire internet a completely false piece of information about Pharrell Williams. It is a lesson in journalistic hygiene.

This is the story of how I may have fed the entire internet a completely false piece of information about Pharrell Williams.

It began, as so many things do nowadays, with a tweet:

@incrediblemelk Hi Mel! I work for the national Danish Tv-station, and I have a question for you. Can you send me an e-mail? [email protected]. TY!

— Mads Mathiesen (@TheAmazingMaze) March 12, 2014

I hesitated to reply because I wasn’t sure if Mads was a real journalist, which seems rather ironic in retrospect. But then the intrepid Dane found me on Facebook.

Turns out he works for Detektor, a show that fact-checks political rhetoric and media spin. (Imagine a Danish cross between The Daily Show and Media Watch.) In 2012, it attracted international attention when it called bullshit on Barack Obama for praising pretty much every country on “punching above its weight”.

Now, Mads was noticing something odd about the media coverage of Pharrell Williams’s career renaissance. Pharrell is popular right now, following his guest spots on last year’s megahits ‘Blurred Lines’ and ‘Get Lucky’, and this year’s album G I R L and Oscar-nominated single ‘Happy’. But was he responsible, as is widely reported, for 43% of songs played on US radio in August 2003?

“This sounds incredible, so I have searched the internet to the best of my abilities, but have been unable to find this exact survey anywhere,” Mads wrote to me. “It is oft-cited, but nowhere does it say who conducted the survey or where to find it.”

I went Googling. Good lord, the stat is everywhere. It’s in Zach Baron’s recent GQ profile: “A survey in August 2003 finds that the Neptunes are responsible for a full 43 percent of songs played on the radio that month.” Last August, Jim Carroll wrote in the Irish Times, “It’s like 2003 all over again. Back then, it was estimated that 20 per cent of the records played on British radio – 43 per cent in the United States – were produced by The Neptunes”. The magic stat was repeated in November 2011 by The Huffington Post’s Brennan Williams, and in February 2009 by Ben Naparstek (now Good Weekend editor) in The Australian.

Perhaps most poignant was Simon Hattenstone’s Guardian interview this month, which debunks notions that Pharrell is responsible for 50 or even 60 per cent of airplay: “In fact, the stat people are thinking of goes back to 2003 … It’s a remarkable figure.”

It sure is. And I promulgated it. You see, almost everyone who mentions the magic 43 per cent and 20 per cent is quoting my Saturday Age feature from May 2004.

“A survey in August last year [2003] found the Neptunes produced almost 20 percent of songs played on British radio,” I wrote. “A similar survey in the US had them at 43 percent.”

Someone added my article to Pharrell’s Wikipedia page.

You can guess the rest.

Where Did I Get Those Statistics?

Flashback to April 2004. The Neptunes’ Wikipedia page was but a stub; Pharrell didn’t even have his own page yet.

I was working three days a week for a scrappy little startup called Private Media, pitching freelance pop culture features on the side. I was fascinated with the mainstreaming of hip-hop and R&B; the previous year I’d presented an academic conference paper about white chicks twerking.

Having just handed in my MA thesis, I was accustomed to scholarly research methods. I was new to journalism and still feeling my way blindly through its rhetorical and ethical codes, but I remember really sweating over this story, taking pains to refer to only articles from well-known news sources, which I retrieved from two online databases: ExpandedAcademic and ProQuest.

Of course, my Neptunes source material had vanished by the time I needed it again last week. Kids, this was before USB sticks, so I routinely used email to transfer my work between the various computers I worked on. Maybe I’d emailed the articles to my long-deactivated university email, or to my old Yahoo! address whose contents were wiped after I switched to Gmail and Yahoo! deemed my account ‘dormant’.

It’s easy to forget how vulnerable information is, how reliant on platforms and proprietary software, and how easily it falls between drives and disks and servers. I thought the guy with whom I shared an office was terribly vain for archiving all his emails to disk ‘for a future biographer’, but I still mourn the intense, epic email and MSN chat exchanges I had around this time, especially my Secret Life of Us recaps for friends overseas. All gone now.

And So My Fact-Checking Journey Began

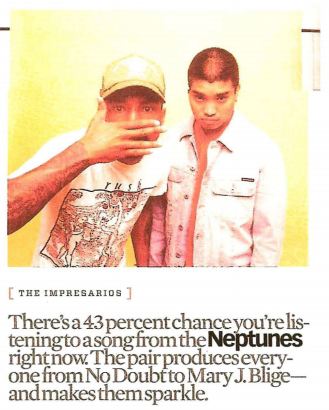

It was pretty straightforward to dig out the relevant articles by returning to the same databases. One was a piece by Neil Strauss in Esquire, December 2002, page 148: “There’s a 43 percent chance you’re listening to a song from the Neptunes right now. The pair produces everyone from No Doubt to Mary J. Blige–and makes them sparkle.”

The other article was by David Smyth in London’s Evening Standard, on 15 August 2003, page 31: “This month a music magazine conducted a survey of radio station playlists and concluded that Chad Hugo and Pharrell Williams, better known as Virginia-based production duo the Neptunes, currently control an incredible 19 per cent of Britain’s airwaves.”

Of course, Smyth doesn’t say which music magazine it was… so I emailed both him and Neil Strauss. The responses I received made it clear that Mads Mathiesen, tipped off by me, was on the same data trail.

David replied: “I would have read it in a mag which was sitting on my desk at that time, but of course has long since been thrown out. At the time I was subscribing to Music Week, Mojo, Q, NME and Time Out London.”

Music Week is indexed in several databases; I found one that scanned the original pages. I searched the issues spanning late July and early August 2003, but failed to find the 19 per cent statistic quoted anywhere. To double-check, I read everything Music Week published about Pharrell Williams and the Neptunes in 2003. Nothing.

When I tried to find the other titles, things got frustrating. The State Library of Victoria doesn’t hold ten-year-old British music magazines in hard copy, microfilm or digital database. Nor were they indexed in any of the databases I’d been searching (although American music magazines were well represented). Rock’s Back Pages, on the other hand, is a wonderful full-text archive — but it’s paywalled. Academic and community libraries can subscribe… but only if they’re in the UK.

I could still search, though, and I felt tantalisingly close to that magic 19 per cent when I discovered Paul Elliott’s profile of Pharrell in Q’s September 2003 issue. When you consider that magazines are routinely sold ahead of their cover dates, this issue could well have been on David’s desk in mid-August. But when I tried to contact Paul Elliott, his trail went cold, obscured in a fog of other, non-UK-music-journo Paul Elliotts.

Meanwhile, my email to Neil Strauss received a very nice reply from his assistant Andrea, attaching a PDF of the article in question. Learning that Neil employs an assistant flooded me with mingled annoyance, inadequacy and grudging admiration. But the message from Camp Strauss was clear: the statistic had not come from Neil’s article, but from its headline written in-house at Esquire.

So I emailed Esquire’s editorial department, asking if anyone still working there recalled this article and enquiring after the source of the statistic. As journalists like to say, Esquire did not respond before deadline.

A Note On Information Hygiene

We all know information goes feral online. Tomorrow’s Woodwards and Bernsteins are doomed to lay their mighty truth-telling investigative scoops before an audience that doesn’t even care if something is true.

Instead, we like our journalism truthy – if information feels right to us, and plays to our existing perceptions and prejudices, then we’ll accept it. As Stephen Colbert says, “You don’t look up truthiness in a book, you look it up in your gut.”

The Neptunes and their various projects were hugely popular between 2001 and 2004. They won heaps of awards. People did feel as if Neptunes songs were on the radio a lot. And Pharrell and his stupid hat are enjoying so much exposure now that the magic stats seem just as plausible.

Of course, the Neptunes themselves, and their representatives, have never debunked the magic stats… but then why would they? The stats quantify their popularity and cultural power. They’re flattering.

It’s easy to blame journalists for failing to fact-check. But as I found this week, actually doing it is still painstaking, time-consuming and often unrewarding. Writing at Esquire, Luke O’Neil beautifully explains that modern freelancers are not noble torchbearers for unimpeachable ethics. Rather, they exist in a fug of cynicism and stress, punctuated with glee at having written something shareable, and despair at participating in “an ourobouros of shit”.

I sympathise. If you had to file a Pharrell Williams story as part of an ever-heavier workload with ever-shrinking resources, you might well make a judgment call that a story published in a broadsheet newspaper, repeated under other reputable mastheads, and unchallenged in a decade except recently at Reddit, is a credible source.

The challenge is keeping accuracy top of mind and cultivating curiosity rather than complacency. The nifty Verification Handbook is an easy-to-follow guide for journalists and editors. It explains how to verify breaking reports, images and video, and practise responsible crowdsourcing.

Another practice of journalistic hygiene is easier to achieve: reading and writing more precisely. In my Pharrell example, I fudged the 19 per cent statistic from my research by phrasing it as “almost 20 percent”… which other journalists went on to report as a flat 20. Some journalists also mistakenly assumed that both the UK and US statistics in my story were from August 2003, when I had phrased them as separate studies.

As Reddit user faithie55 noted, “It’s not possible for [the Neptunes] to have produced 20% of the songs played on British radio. What is entirely possible is that 20% of airplay is Williams songs. Why can’t even journalists use the language properly?”

To which another user retorted: “Downvoted for being a know it all”.

–

Mel Campbell is a freelance journalist and cultural critic, and author of the book Out of Shape: Debunking Myths about Fashion and Fit. She blogs on style, history and culture at Footpath Zeitgeist and tweets at @incrediblemelk.