A Talk With The Very Intimidating St. Vincent

Annie Clark doesn't like to repeat herself.

Annie Clark doesn’t like to repeat herself.

In ten years, Clark’s released six albums: five as St. Vincent, plus Love This Giant, a collaboration with David Byrne. Since moving on from the relatively subdued 2000s indie folk of Marry Me and Actor, she’s made a point of transforming St. Vincent with each album.

“I kind of feel like I’m a kid with a chemistry set going ‘What happens?’,” Clark tells Music Junkee over the phone from Los Angeles. “It’s just a lot of fun and a lot of experimenting and a lot of pain and a lot of absurdity, all rolled into one.”

Her first album was 2011 breakout Strange Mercy, which matched existential dread with shattering guitar solos and unsettling Valley of The Dolls imagery. Then, with St. Vincent’s self-titled follow up, Clark commanded attention: reviewers regularly called her one of rock’s most innovative guitarists, and for unbelievers, she created a cult-like persona and a live show that doubled as induction. As of last September, we’re in the era of St. Vincent’s fifth album Masseduction, her most pop-leaning record yet, produced by Jack Antonoff.

In line with the current trend of confessional-obsessed pop music consumption, where every second single appears to reference a scandal, Masseduction is notably much more personal than previous efforts.

It jumps between inescapable heartache (‘Los Ageless’) and David Bowie’s death (‘New York’), addiction and overdose (‘Pills’, ‘Young Lover’), death (‘Slow Disco’), self-doubt (‘Smoking Section’). But overarching the album is the spectre of fame, as in 2016, Clark became tabloid bait while dating supermodel Cara Delevingne.

To Daily Mail readers, she was known as the “female Bowie who saved Cara”. To fans who were promised her most personal album yet, the lyrics pointed to their relationship, which Clark remains quick to reject as limiting.

Unlike Antonoff’s other high-profile collaborators (Lorde, Taylor Swift), St. Vincent remains committed to the deeply uncanny, balancing pop with apocalyptic guitars and bizarre posturing — Clark regularly describes her guiding concept as “dominatrix at the mental institution”. True to word, Clark’s combined her own emotional pains and power struggles with a PVC-heavy aesthetic, as Masseduction marries St. Vincent’s slightly masochistic sense of humour with Antonoff’s distinct knack for quirk-driven ear-worms.

Ahead of her mini-Australian tour this June, Clark talked to Music Junkee about Masseduction‘s reception from critics, tabloids and Coachella crowds alike, as well as how she makes creative choices by laughing at them.

The last time we saw you was at Coachella. How did you find the audiences?

Well, I mean I feel like Coachella now is almost more about capturing it for posterity [and] the people watching from home than it even is about the people there.

I only ask because I’m in Sydney every year, and it can be a little frustrating to be watching at God only knows what hour and to see the placid crowds, and it’s like, ‘Dance! I’m dancing in my bed’.

I do have to say, I think the first weekend is a little bit more of the social scene and the second weekend is more people just so amped to see this music and that music.

I didn’t get to see a lot of the bands, but I did definitely get to hear people’s sets from afar and I just felt like so many artists were basically pleading with the crowd to give ’em something, like I heard so many, “Come on, Coachella! Give me some noise! You can do better than that!”

Like I heard a lot of negotiating with the crowd for enthusiasm, which I thought was… we’ve all been there, don’t get me wrong. I’m not being snide, I just, like, ‘eurgh’. ‘Eurgh’.

The set was also your debut of a new full band set, which was a complete 180 of your solo touring show. Which can we expect in Australia?

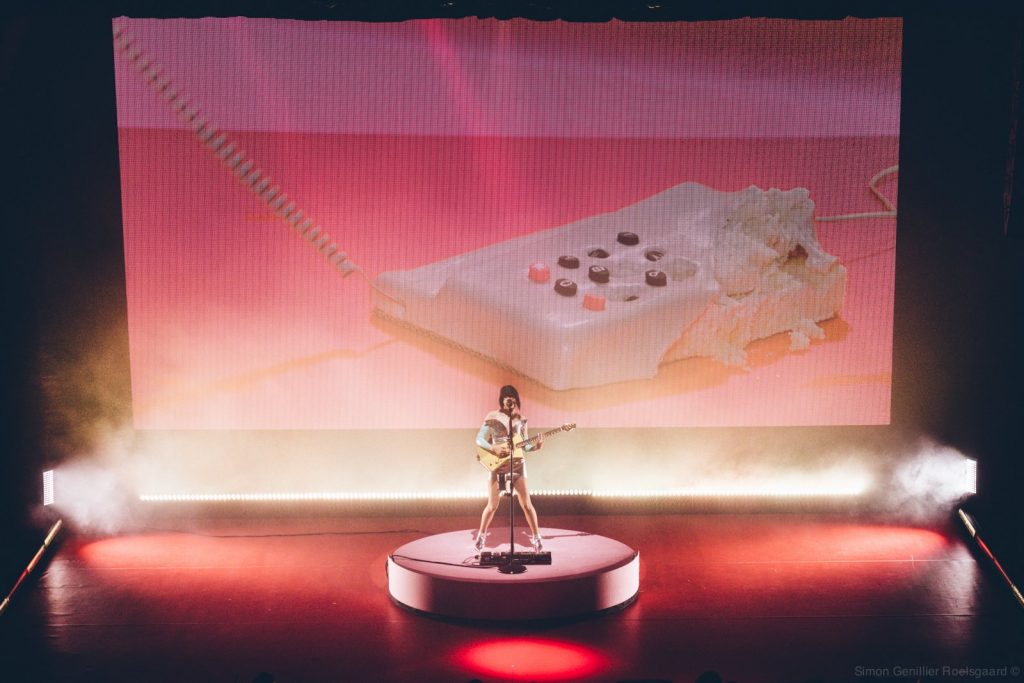

Well, because the Australian venues [Sydney’s Carriageworks and Hobart’s MAC2] are like big theater-y spaces, I thought it would be more appropriate to bring my theatre show. So that’s what I’ll be doing in Australia and Tasmania.

Photo via St. Vincent Facebook page

Which definitely relates to the record’s aesthetic. When Masseduction was released, you said, “If you wanna know about my life, listen to this record.” Now, it’s been out a few months, did you expect to have the album’s lyrics mined so much as they have been?

Have they been? I don’t know.

I would say so. Do you read many of your reviews?

I mean, I read a couple — kind of — at the very beginning, but no. So I don’t really know.

Throughout Masseduction, there are lots of whispered, obfuscating lyrics. I couldn’t help but imagine Daily Mail reporters screwing up their faces while listening, trying to write stories about your past relationships.

I can assure you I wasn’t thinking about the Daily Mail when I was writing this!

It was the furthest thing from my mind. I mean look, you know, it’s not a fact, factual blow-by-blow. It’s art, it’s one sliver of a point of view of a period of time and a person trying to make sense of that period of time.

People are gonna think whatever they think about it regardless of any kind of tabloid stuff: people are gonna wonder what this is about or put themselves into it or take it and deconstruct it and use only the parts they like.

Whatever, that’s just how music is. You get it and then you use it however you see fit, and so that kinda plays into that for me, once I’m done with the record, it’s not for me anymore. It’s for everybody else. And also I kind of go back to that old adage, ‘what people think of me is none of my business’.

A lot of Masseduction‘s songs are a counterpoint to each other, the most obvious being ‘Los Ageless’ and ‘New York’. Correct me if I’m wrong, but ‘Sugarboy’ features a sped up guitar from ‘Los Ageless’, is that right?

Yep.

How does that come about when you’re writing?

With ‘Los Ageless’ and ‘Sugarboy’, they shared some DNA ’cause originally they were the same song. And then there were just too many ideas for one song — I love Rush, but I just wasn’t going for a prog odyssey on this record.

So they became two songs and really started to have their own identities and everything. But the fact that they were one [left] a fossil in ‘Sugarboy’.

And with ‘Los Ageless’, was it a case of “Oh, well now I’ve gotta write the west coast song?” Or is the counterpoint more natural?

Originally I really wanted every song on the album to have a twin — to have a point and counterpoint, as you put it. It just didn’t end up being every single song.

I think you can feel very strongly about something one way and then a few minutes pass or you get distracted or you forget about it. Time passes and you come out the other side of it with a totally different point of view, so I wanted to kind of honour that aspect of life. But yeah, not everything ended up with a twin. But certainly, those two were deeply related.

And then in ‘Slow Dance’, there’s a Sliding Doors image of wanting to see all your potential lives. Is this an album exploring all of those different potentialities?

I don’t know. I mean, that’s an interesting theory. I can’t really speak to it. I had to pick one potentiality and record it. [Laughs]

Your current tour is called ‘Fear The Future’, after the album track of the same name. There’s a lot to be scared about in the world right now, but what helps you calm those fears?

To be honest with you, I called that tour ‘Fear the Future’ because it made me laugh because it’s so bleak and so funny. You’d be surprised how much humour actually plays a big part in me making decisions. If I come in and listen to something and it’s like, bizarre and makes me laugh, I’m like, “Yeah, let’s do it!”.

I don’t know how apparent that would be [listening]. I mean this whole album is sort of, from the visual side of it, exploring “where do sexy and absurd intersect?” And [with] “dominatrix at the mental institution”, it’s like, “what is that line?”

With the recent tour that I put together and premiered at Coachella, the basic principle of it was, “Is this okay?” I needed to be asking myself “Is this okay?” About basically every decision and if the answer was “I don’t know.” Then the answer was, “Yes. We’re doing it.”

That comes across in your Vevo interview with Jack Antonoff, who co-produced the album. You do a lot of joking around — in the interview, you kept doing this silly hand motion–

Oh, yeah. It’s like hang-ten, like a surfer thing.

Yeah! In Australia we call it a shakas. Have you shaken it off yet?

No, I still do it. I’m not sure that I should. [Laughs]

The reason I think it’s funny is ’cause like between me and Jack Antonoff, we’re not like ‘flowers and peace’ and ‘go with the flow’ people, ever. In a certain way, we’re both pretty high strung and sort of like a little neurotic.

So that’s why I think the shocker, whatever, is very funny, because it’s so incongruous.

Evidently, you have a fruitful collaborative relationship with Antonoff, as do many others. What is that makes him such a great collaborator?

I think it’s his spirit and his generosity. He’s like the ultimate cheerleader. You can be trying something and kind of be like, “Ooh, I’m out on a limb. I don’t know what’s… I don’t know what I’m doing here.” And he’s just behind you a hundred percent.

And that’s just so valuable to have somebody like that in your corner. Because the thing that you’re doing might not be the exact thing, but the fact that it didn’t get stamped out at the beginning [means] it gets to evolve naturally into something kind of better than it would have been, had you stopped the idea.

I think his positivity and his humour make him — obviously his talent [too], but so much of being a producer is this interpersonal thing. Being a producer is being part therapist, part manipulator, part cheerleader.

…Best friend, manipulator, teacher, parent, everything in one.

All the things.

—

St. Vincent is playing at Vivid Sydney and Dark Mofo this June.

—

Jared Richards is a staff writer at Junkee, and co-host of Sleepless In Sydney on FBi Radio. Follow him on Twitter.

—

St. Vincent article image by Nedda Afsari