Inside Australia’s Most Intense Songwriting Camp, Where Your New Favourite Tracks Are Written

What happens when the writer of 'Despacito' works with Australia's brightest?

As if it’s the first day at school, the energy ramps up as SongHubs’ 30+ artists begin to arrive to Studio 301, a recording studio in Sydney’s industrial Alexandria which will be their home for the next four days.

A steady mix of emerging talents, Australian mainstays and international heavy-hitters trickle into the foyer. At first, it’s one at a time, then all at once, which is when polite chatter gives ways to screams and shouts, as artists spot old collaborators or familiar faces from previous SongHubs — or just from around town.

By the week’s end, 37 clean and crisp pop songs will be written and recorded, if not near radio ready. But before the participants are paired off and stuck in a room until 6pm, they have to meet, which for the newbies is essentially speed-dating at its most extreme.

“It’s kind of like, ‘Nice to meet you! Let’s write about your trauma!’,” songwriter Bri Clark tells me a week later on the phone from Perth, where she lives. Her travel time isn’t quite as far as UK’s Starsmith (the producer behind Clean Bandit’s absolute ear-worm, ‘Real Love’), or ‘Despacito’ co-writer Erika Ender’s, who arrives straight from Sydney airport, but it’s still quite a commitment — especially when you’re unsigned, as Clark is.

Isabella Manfredi and Steve Soloman. Photo: Serena Petriella, @facesbyglow

But even with the overheads — flights, taking time off work — she tells me it’s 100 percent worth it for the chance to work with people who have made literally millions from crafting a perfect piece of pop.

“And this SongHubs was the all-stars SongHubs,” she says. “It was filled with incredibly diverse writers and artist and producers — and some really well-known artists [writing] for people they didn’t know who they were.”

Despite that, Clark says there’s little ego; everyone’s treated equally in the studio, as everyone’s earned their spot at the camp. Still, that doesn’t mean, in Clark’s own words, that it’s not “really fucking terrifying”.

“To be a relatively new songwriter in the scene, I still feel like I have to prove myself in every room that I get into,” she says. “I love the challenge. I love being thrown into the fire and seeing what comes out…. [And] when every person in the room can just work together in such synergy that they create something bigger than the sum of our parts — that’s literally the greatest feeling in the world.”

Wait, What’s A Songwriting Camp?

While we might imagine our favourite artists fighting through their feelings by scratching out lyrics and a melody in a fugue, the reality is that a heap of major-label music is written within songwriting camps. It’s not just for the Britneys of the world, either: programs like SongHubs have resulted in hits for the likes of Cub Sport, Ecca Vandal and Tkay Maidza, too.

How does it all work? Well, rather than have one person write a song, camps combine producers with artists and top-liners, songwriters who focus on lyrics and melody, aka what’s attached to the bones of a track.

“When every person in the room can just work together in such synergy that they create something bigger than the sum of our parts — that’s the greatest feeling in the world.” – Bri Clark

Often a camp will be organised by a label around one artist, but more nebulous programs like SongHubs — organised by music rights body APRA AMCOS — are common too, connecting talents in unpredictable, otherwise improbable ways.

“They come in at 10 o’clock and by six o’clock they deliver a song,” says SongHubs director Milly Petriella. “And it’s done! People have asked me, you know, ‘Why don’t you give people two days or three days?’ But it just changes the flow — [it’s better] if you do put that little bit of pressure on creators to deliver by the end of the day. I tried one once where the sessions went for four hours and they did two a day. Everybody delivered, but it was full on.”

Jess And Matt, Thief. Photo: Ruby Boland, @rubyboland

Songwriting camps have slowly become a staple of pop since the late ’90s, around the same time Swedish studios like Cheiron (where Max Martin earned his chops) became the hit factories they are today, as detailed in John Seabrook’s The Hit Factory. It’s why many songs now feature 10+ credits — and why some of those liner-notes might seem like mad libs. Father John Misty, Diplo, Ezra Koenig and Beyoncé all walk into a bar, and write ‘Hold Up’.

Cynics call it clinical — or write Black Mirror episodes about trapped pop stars — but it’s really just about putting creatives in a room together and seeing what happens, albeit at a mass scale.

Not All Songs Will Be Sung

By a camp’s end, there could be 100s of demos. They can either be whittled down into an album, held onto for a later ‘era’, shopped and sold around — or discarded completely.

At SongHubs, APRA AMCOS gets each group to sign a royalty agreement at the end of each session, agreeing on the percentage split right then and there. But typically, it’s not a quick process — if it’s released at all. Petriella tells me that John Butler Trio’s ‘Home’ took four years from camp to release. She says sometimes the song is simply ‘ahead of its time’, or not quite right for an artist’s current album.

“There’s a million reasons why that happens,” she says. “But I do think it’s about the infrastructure — everything they have to go through [to] finding the money for the marketing. Or the song itself is maybe ahead of its time, [or ahead for[ the sound of that artist at the time. Then, four years later it’s perfect.”

Other times, it’s shopped around for the perfect act, or tinkered with until it’s absolutely perfect, as was the case with ‘The Middle’, Zedd and Grey’s huge 2018 hit with Maren Morris (though strictly speaking, that didn’t come from a camp). As the NYT detailed last year, that track — written by Australia’s own Sarah Aarons — took a year and demos from 14 huge pop stars, including Charli XCX, Carly Rae Jepsen and Camila Cabello, to get it right.

Then again, sometimes it’s super quick. Briggs’ blistering satire of white privilege ‘Life Is Beautiful’ — a song far-flung from the soulless pop outsiders imagine the hit factory making — was written at a SongHubs camp last October, and released this April. And after this SongHubs, CXLOE keeps working on ‘Half Of Me’, a song written at 301 Studios with Chloe Angelides and Msquared. Two weeks later, she’s playing it live across her headlining East Coast tour.

Since APRA AMCOS began SongHubs in 2013, more than 100 songs have seen the light of day, and a quick scroll through the SongHubs Spotify playlist will show the breadth of genres and artists, with names ranging from Montaigne to The Chainsmokers, Urthboy to LeAnn Rimes and Peking Duk.

But most songs won’t be released, which is truly wild, considering the calibre.

Walking between the studios, you hear hooks that sound ready to be blasted from a car radio; huge, magnetic vocals; an interesting, clever lyric; an odd beat. And while plenty have potential, many will be left in time, as producers realise it’s missing something no one can add in. There’s a science to pop, but there’s an element of magic too: they know if it’s just not there.

SongHubs’ Birthday Bash

Cxloe. Photo: Serena Petriella, @facesbyglow

This April SongHubs is special — it’s the 60th camp, which is why is has a bit of an unofficial ‘all-stars’ line-up.

“When we first started this,” says Petriella, “I couldn’t pay anyone to come to Australia…[And] no one gets paid to do SongHubs. When you’re looking in from the outside, you think, ‘Why?, You know?’ We fly them economy, we bring them over to Australia, they’re not getting paid and they’re mostly writing with people they’ve never heard of.”

“[But] now through its reputation, and we have so many great songs that have been released — and are earning a bucket load of royalties for songwriters — people are very interested. Australia isn’t too hard to get to anymore.”

Internationally, SongHubs has a name for itself, having held genre- and continent-hopping camps in London, LA, Bali and Nashville, and currently averaging around 12 camps a year. The big plan for this year is the first Korean SongHubs, with the aim of allowing Australians to crack into the k-pop market.

Walking between the studios, you hear hooks that sound ready to be blasted from a car radio; huge, magnetic vocals; an interesting, clever lyric; an odd beat.

That’s the real point; getting Australian talent known outside of our own shores, when previously they’d been cut out of these camps. While Petriella isn’t taking away from her own hard work, she says SongHubs is a much easier sell now we have so many writers and artists repping the antipodean.

“[The era where] no one really knew what was happening with the industry here is way gone,” she says. “We can thank [Lorde and Taylor Swift producer and co-writer] Joel Little, Sia, Vance Joy, Courtney Barnett and all of the Aussies that are doing so well globally that we’re now really recognised as being up there with the best. And so it’s not hard to get the internationals on board.”

CXLOE and Erika Ender. Photo: Serena Petriella, @facesbyglow

Which means alongside Starsmith and Ender, this SongHubs’ international guests include the likes of Chloe Angelides, Steve Solomon and ex-Evanescence member David Hodges. Between them, they’ve worked on hits for Ariana Grande, Selena Gomez, Nicki Minaj, Demi Lovato and Carrie Underwood — and that’s just skimming their CVs.

Meanwhile, on the Australian front, there’s a steady mix of artists like Isabella Manfredi and dark-pop pioneer CXLOE, as well as established producers and emerging writers, such as Clark and Rory Adams, a 17-year-old wunderkind from Adelaide.

“It’s life-changing, it’s career-changing,” says Clark. “if you write an amazing song in front of those masters of craft, people notice you.”

Producing (The Perfect Environment For) Pop

Each guest and songwriting group is hand-picked by a curator — this SongHubs’ is under the watchful eye of Georgina McAvenna, an A&R expat who, among other things, signed Kesha and Bruno Mars, and was the first to discover King Princess. In short, the guests are in good hands.

“One of the great things about the curators [is that they] don’t necessarily know the Aussies until they receive the applications,” says Petriella. “We’ve discovered people that we didn’t even know… because they’ve applied and the curator has gone, ‘oh my God!’, based on no preconceptions.”

McAvenna has flown in from LA for SongHubs, and despite the jet-lag, she’s energetic when we chat a few days into the program. She’s heard snippets, and has been consistently blown away by the calibre — even from the more wildcard pairings.

Photo: Ruby Boland, @rubyboland

“Magic can happen, like putting together different combinations of people,” she says. “I’m always very strategic behind combinations — there’s always a rhyme and a reason to it, but ‘mismatches’, [that’s] where some of the magic comes from.”

That and the time pressure, she says. One of the only strict rules of SongHubs is that a song must be handed in at 6pm each day.

“[With] the really clear song a day [rule], you have to go in with a bunch of people you’ve never worked with — who are strangers — and then, you can’t mess around,” says McAvenna. “You have to be precise and disciplined with the decision-making. If you have it open-ended, people can labour over the process of making the song [and] the production. You’ve just got to get it done and to live with the song at the end of the day.

“And you know, the other part of it… it’s super supportive and everyone’s all there for each other, but there’s also a healthy bit of competition between all the producer rooms. Not that the stakes are crazy high, but the pressure’s on… I noticed that some of the producers last night didn’t go to dinner, and went back and took their gear and were working on this stuff at night or this morning.”

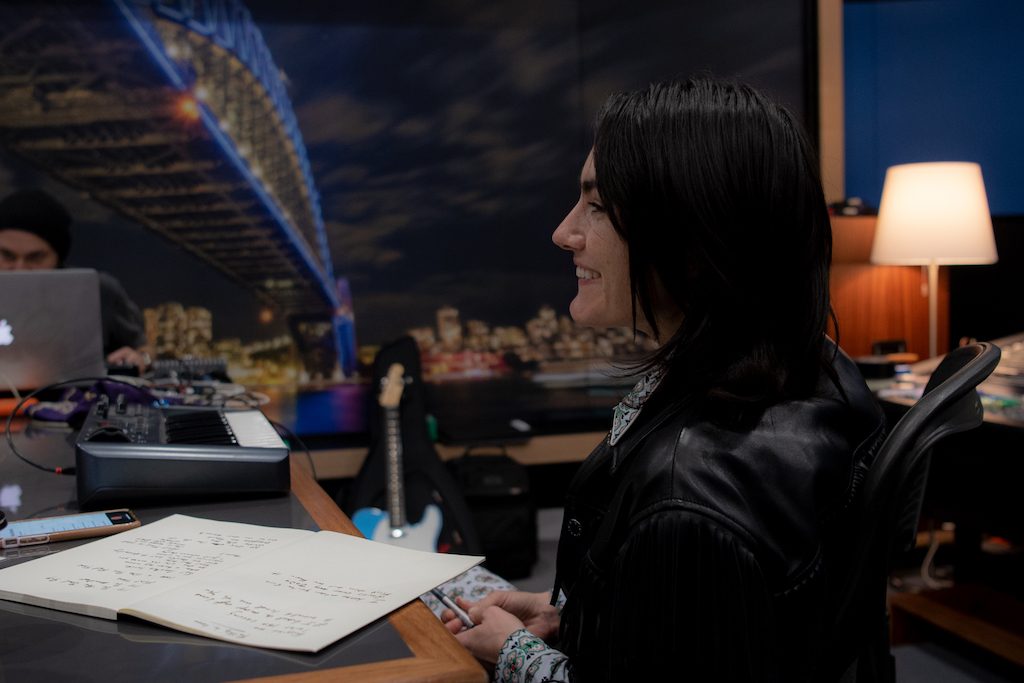

Isabella Kearney-Nurse, Bri Clark and Starsmith. Photo: Serena Petriella, @facesbyglow

That’s because at the end of the four days, there’s a listening party, where producers play 1 or 2 of their top tracks of the camp.

Cheese and crackers come out, as does booze and balloons. People get up and dance and shout, but a sharpness still lingers, like static in the air before a storm. Everything cracks when UK producer Starsmith plays a huge EDM ballad called ‘Don’t Love Me’, co-written by Bri Clark and Sydney’s Isabella Kearney-Nurse, finished just a few minutes before the party.

Clark sings the demo. At the bridge, her voice booms and shakes with intensity as she sings about a break-up — an amalgamation of the two writers’ lives. Recording, she took 10 or so goes to get it right, but it was worth it. It’s since been shortlisted for this year’s Vanda & Young Global Songwriting Competition, a massive deal for an unreleased demo.

As she hits the highest note, you actually see several people sit upright. Afterwards, a group of international producers at the back of the room whisper to each other, double checking who sung it. The song might never see release, but at least now it’s in the machine.

Jared Richards is a staff writer at Junkee, and co-host of Sleepless In Sydney on FBi Radio. Follow him on Twitter.

Feature image by Ruby Boland.