So, Season One Of ‘Serial’ Is Over. What Have We Learnt?

Y'know, apart from the correct pronunciation of Mailchimp.

Contains spoilers for the season final of Serial.

–

It’s happened. Sarah Koenig has been played out by that piercing yet hypnotic piano theme one last time, and you’re still no closer to getting that sweet moment of whodunnit relief. Funny or Die weren’t so far off; Koenig couldn’t give us the smoking gun. But did you really expect her to? This isn’t Cluedo, and we’re not searching for The Yellow King. These are people’s lives and, as great as she is, Koenig isn’t a defence attorney or special prosecutor. She’s the one who asks the questions.

Though the stories of the murder of teenage Hae Min Lee and the conviction of her ex-boyfriend Adnan Syed are far from over — DNA tests are still pending on Hae, and Adnan still has an appeals hearing coming up next month — season one of Serial is now done. And after being let into their story over twelve weeks, and coming out the other side, it’s kind of difficult to see the point in it all.

Was it a true crime mystery? Was it a legitimate chase for justice? Despite Koenig’s adamant claims that the project was all in the name of journalism, it’s hard to deny its appeal as straight entertainment. Loaded with suspense and intrigue, Serial was storytelling at its finest; a tragedy made all the more tragic by the fact that it was true.

Though Koenig’s thoughts may have spun us around and landed us back where we started, we’ve definitely come out of Serial with a lot to think about. Despite all the story’s ambiguity and frustrating dead ends, here are some things we have learnt.

–

Serial Was In An Ethical Grey Area

So, here’s the crux of the thing: though Serial‘s been heralded as revolutionary for its form, and flatteringly compared to popular television series such as House of Cards and Game of Thrones, it has one crucial difference. As Stephanie Van Schilt writes in her excellent discussion for Spook, “[the] entertainment factor leaves a bitter taste because Lee isn’t Laura Palmer … Lee is real and she’s dead.”

This doesn’t — and shouldn’t — make the story off limits, but it does create some problems. Swept up in the frenzy following the show’s unprecedented success, the story started to take precedence over the real people involved. The producers began releasing merchandise:

Holy cash grab. RT @ThisAmerLife: Pre-orders have shipped! Now in stock: the @Serial notebook. https://t.co/YOiasjhYSG

— Matt Adams (@2015WhiteSox) December 16, 2014

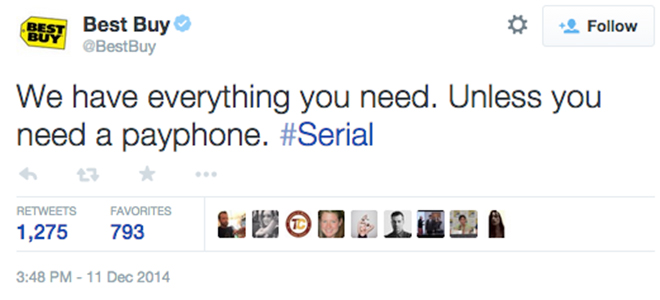

And companies mentioned in the story even tried to glean some of the spotlight:

This is far from the twisted kind of ‘serial killer chic’ that sees people peddling locks of Charles Manson’s hair, but it’s still icky. The fandom that followed the podcast was not that of a concerned citizen watching an investigative report on the news. People craved the plot twists and drama of HBO, and Koenig was playing a familiar role. Outwardly you knew she was a reporter; a skilled storyteller just doing her job. But when you were four episodes deep in the course of a day, she was basically a character from True Detective.

Just like in the “Dead Girl TV” we’re becoming increasingly accustomed to, we were trying to piece together the jigsaw. Koenig let us in on her process with the same trepidation and self-doubt as a better-spoken Rust Cohle, and more than 700,000 people took to Reddit per month to help solve the crime.

All this went on with apparently little sensitivity or thought given to the victim’s family. “To you listeners, it’s another murder mystery, crime drama, another episode of CSI,” said Hae’s brother, in a post on Reddit last month. “I pray that you don’t have to go through what we went through and have your story blasted to 5 million listeners.” (Redditors have since established a memorial scholarship in Hae’s name.)

In many ways, Serial was like Truman Capote’s In Cold Blood. Though it didn’t blend fiction with fact, it did create a uniquely controversial way of presenting real events. Much like the true crime novels your nan devours on airplanes and Christmas vacations, Serial was a story — one “told week by week” with all the styles and structures of a pulp read. Koenig’s tale was stacked with ominous silences, niggling suspicions and stock characters. Hae was the innocent young girl penning love letters in her diary. Adnan was the upstanding young man who prayed, and played fun team sports. Jay was the unknown; the dodgy stoner who worked at a porn shop. Each detail was deliberate.

And as Linda Holmes noted for NPR, this isn’t necessarily a bad thing. “[The true crime genre has] a fascination with the way the system doesn’t work in logical ways, but also an appreciation of the way people don’t work in logical ways,” she says. “Crimes are a rich topic for people who are fascinated by behaviour, in part because they leave records. They are investigated, documented, researched, contested, vetted. Imagine if you could do this with breakups or firings or family arguments. Imagine if there were a file about your worst breakup in which everyone had been interviewed.”

Putting aside its much-discussed issues with “white reporter privilege”, the larger problems Serial has are also common to all kinds of narrative reportage. As Janet Malcolm famously said in The Journalist and the Murderer, “Every journalist who is not too stupid or full of himself to notice what is going on knows that what he does is morally indefensible. He is a kind of confidence man, preying on people’s vanity, ignorance, or loneliness, gaining their trust and betraying them without remorse.”

This unavoidable sense of entitlement led to countless parodies:

Throughout the course of the story it becomes clear how aware of all this Adnan actually is. Whether snapping at Koenig about how she doesn’t really know him at all, or asking her about the ending in the final episode, the story was never really his to tell, or ours to solve — for better or worse, it was about Koenig’s search and all the frustration, confusion and heartbreak therein.

–

It Wasn’t All For Nothing

In this last episode, Koenig asks a question that feels both absolutely necessary and incredibly painful: “Did we just spend a year applying excessive scrutiny to a perfectly ordinary murder case?” She goes on to ask legal professionals who assure her the answer is no. But, in lieu of any proof of Adnan’s innocence, some doubt remains.

It’s entirely possible this story has just elicited intense global sympathy for someone who murdered an innocent young woman.

This may be hard to face with a clear conscience, but it doesn’t eclipse the more specific concerns of Koenig’s story. Why was the burial site not DNA tested? Why did his lawyer not offer him a plea deal? Were the defendant’s race or religion used unfairly against him? What was the reason for all these inconsequential lies? Why, in a system that accounts for ‘reasonable doubt’, did a jury find the evidence compelling enough to convict a 17-year-old boy to life in prison?

As Sarah concludes, as a person she doesn’t know the answers, but as a juror she’s obliged to acquit.

Regardless of Adnan’s innocence or guilt, there was a story worth telling here and it’s got a lot to do with the American justice system at large. With the grand jury recently coming under severe scrutiny following the deaths of Michael Brown and Eric Garner, it’s becoming increasingly clear that justice doesn’t always get served.

In this way, the bittersweet uncertainty of the season finale is deliberate. It may not have had the Hollywood ending many hoped for, but that’s just the thing — it’s real life, and real life is messy. Despite Koenig’s extraordinary efforts, she comes up wanting; mired down in the same suspicions, speculations and lack of solid proof of everyone else in the story.

When those familiar chords were struck to signal the end of the season, I felt extraordinary grief and sympathy for Hae and her family, an enduring scepticism of all those implicated in the murder, and a useful sense of outrage at the unwieldy and serendipitous nature of legal process. It may have been complicated, but it was more honest than simple closure.

Whatever you thought about the final episode, it’s safe to say that Serial has started something special. It’s dragged the antiquated, near obsolete form of the radio play into the 21st century and packed it full of an intriguing hybrid of investigation and storytelling that’s captivated the world. In the face of ongoing assumptions about how impatient the internet has made us, Sarah Koenig and her team made this periodic longform journalism the most popular podcast in the US, Canada, UK and Australia. It was the fastest to ever reach five million iTunes streams or downloads and consistently pulled in an average of 1.2 million listeners per episode. It’s an inspiring success for those bastions of traditional media struggling to find their place in the age of new media — if a radio play can make it, anything can.

Listened to the final episode of Serial – a good job, all the challenges considered. People will be talking about Serial for a long time.

— Leigh Sales (@leighsales) December 18, 2014

It may have forced us to battle some serious ethical dilemmas, but this was true crime at its most innovative and productive. Hopefully we’ll be a little more prepared and a lot more wise when the second season rolls around.

–

Meg Watson is Junkee’s staff writer and weekend editor. She tweets from @msmegwatson