20 Years Of ‘Neon Ballroom’, The Album That Saved Silverchair

'Neon Ballroom' was the album that changed Silverchair forever - and the album that may have saved Daniel Johns' life.

“Here we go again. Off into music-land.”

— Content warning: This article makes reference to self-harm and eating disorders. —

According to legend, as detailed in Jeff Apter’s Silverchair biography Tomorrow Never Knows, these are the words that would come out of David Helfgott’s mouth before every take while recording ‘Emotion Sickness.’

The eccentric pianist, best known for his portrayal in the 1996 biopic Shine, plays piano on the opening track to Silverchair’s third studio album, Neon Ballroom, adding his discordant but beautiful style of playing to the song’s sweeping orchestration and dramatic tension. It’s hard to imagine the song without him.

While one could view Helfgott’s words as just a cheery bit of eccentric nonsense from one of the more out-there concert pianists of all time, there’s also a deeper meaning to read into. For someone like Helfgott, “music-land” means the escape — as someone who has spent a lot of their life in the throes of mental illness, playing music is a chance to enter a space of solace and respite.

Playing music, for many, cures what ails them — and, within this framework, one can look at Neon Ballroom as the album that saved Daniel Johns‘ life.

By entering his own “music-land,” Johns was able to channel the demons that had followed him since the band’s explosive rise in the mid-90s. In turn, he saw out the decade by trying to kill what he created. Ultimately, Johns had to kill Silverchair as we knew it in order for it to live on — and the band rarely felt more alive than on Neon Ballroom. In its 20th anniversary year, we’re going to relive Silverchair’s rebirth — its aggression, its vulnerability and its surviving legacy.

Spawn Again

If the swelling strings and discordant piano weren’t enough of a signal, Neon Ballroom makes one thing exceptionally clear: We’re not in Frogstomp anymore, Toto.

While Freak Show dipped its toes in the water as far as experimenting with the band’s form was concerned, Ballroom is an album that throws itself into the deep end without any regard for whether it will surface or not. It’s a unique bridging point between the alt-rock and post-grunge that defined the band’s first two albums, and the focused pop that defined their final two — so much so that one could argue it’s the most singular and distinctive album in the band’s canon. It’s not the sound of a band aping its heroes — it’s the sound of a band shedding its skin; an ugly but nonetheless necessary process of evolution.

It’s the sound of a band shedding its skin; an ugly but nonetheless necessary process of evolution.

Neon Ballroom is an album that hits hard. Not every track would necessarily be thought of as heavy — at least, from a sonic standpoint — it’s all in the way the band plays and how it navigates each musical passage. Ben Gillies sounds like he is hitting his drum kit with hammers for basically the entirety of the record, pummelling through Bonham-sized fills and smashing snare rolls even if the band are technically in ballad territory. Chris Joannou, too, holds down thick, snarling low-end bass lines across the album’s runtime — see ‘Steam Will Rise,’ or the rolling, noisy ‘Satin Sheets.’

Apart from Helfgott, the album is also brushed by the furthered use of keyboards and synthesizers — provided by Midnight Oil’s Jim Mogine and longtime Johns collaborator Paul Mac. They let off siren alarms during ‘Anthem for the Year 2000’ and ‘Spawn Again,’ while a Hammond organ coos beneath the emotional intensity of ‘Ana’s Song (Open Fire)’.

It became such a distinctive part of the band’s sound that they would tour from therein with a keyboardist — sometimes even two. Orchestration, too, weaves into some of the record’s more emotionally tender moments, particularly ‘Paint Pastel Princess’ and ‘Black Tangled Heart.’

Normally a sign of rock-star excess – see ‘There’s a World’ from Neil Young’s Harvest for one of the worst recorded examples – the orchestra feels vital to these moments on the record, adding further dramatic tension to a record that’s already thriving off of it.

In terms of songwriting, Neon Ballroom never entirely allows for the calm to set in. Both ‘Ana’s Song’ and ‘Miss You Love’ feature segues during a verse that turn the song into something guttural and aggressive, even if just for a moment.

For the former, it’s when Johns sings “Sandpaper tears/Corrode the film,” backed by thunderous toms and heavily distorted guitar — it lasts all of five seconds, but it’s such a tonal shift that your ears prick up every time. In the latter, a similar switch is flicked during the line “It’s just a fad/Part of the teenage angst brigade” — in itself, an excellent piece of text-painting and sneering self-reference.

“I wrote Neon Ballroom in that time where I hated music,” Johns said. “Really everything about it, I hated… but I couldn’t stop doing it. I felt like a slave to it.”

It doesn’t stop there, either. In ‘Dearest Helpless,’ Johns gets all but a second into a Nirvana-esque clean guitar sweep before it is offset by a thudding triplet executed by all three members, in turn giving the song a dizzying time signature change. Both ‘Black Tangled Heart’ and ‘Point of View’ send the song through churning, dissonant passages at odds with their more restrained nature.

In an interview with Andrew Denton for Enough Rope in 2004 while promoting The Dissociatives’ debut album, Johns openly admitted to coming at music from an antagonistic place at this point in his life. “I wrote Neon Ballroom in that time where I hated music,” he says. “Really everything about it, I hated… but I couldn’t stop doing it. I felt like a slave to it.”

Sabotaging these otherwise tranquil moments on the album, then, could well be read as Johns’ revenge — a permanent reminder that nothing gold can stay. This is an album of exorcising demons — and, as the story goes, Johns had plenty surrounding him.

Black Tangled Heart

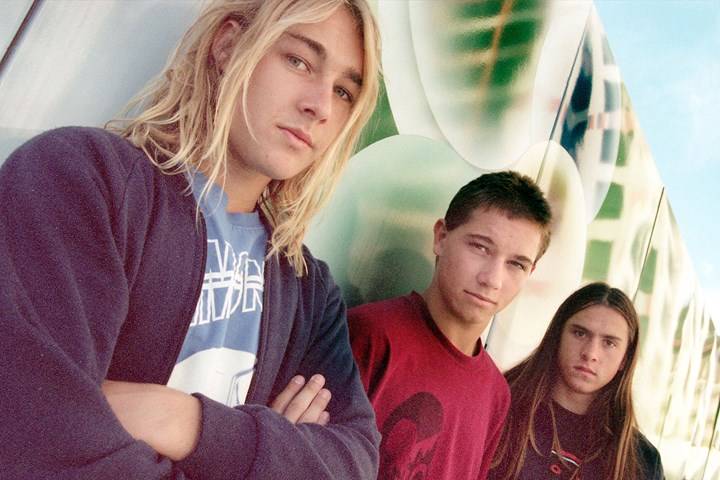

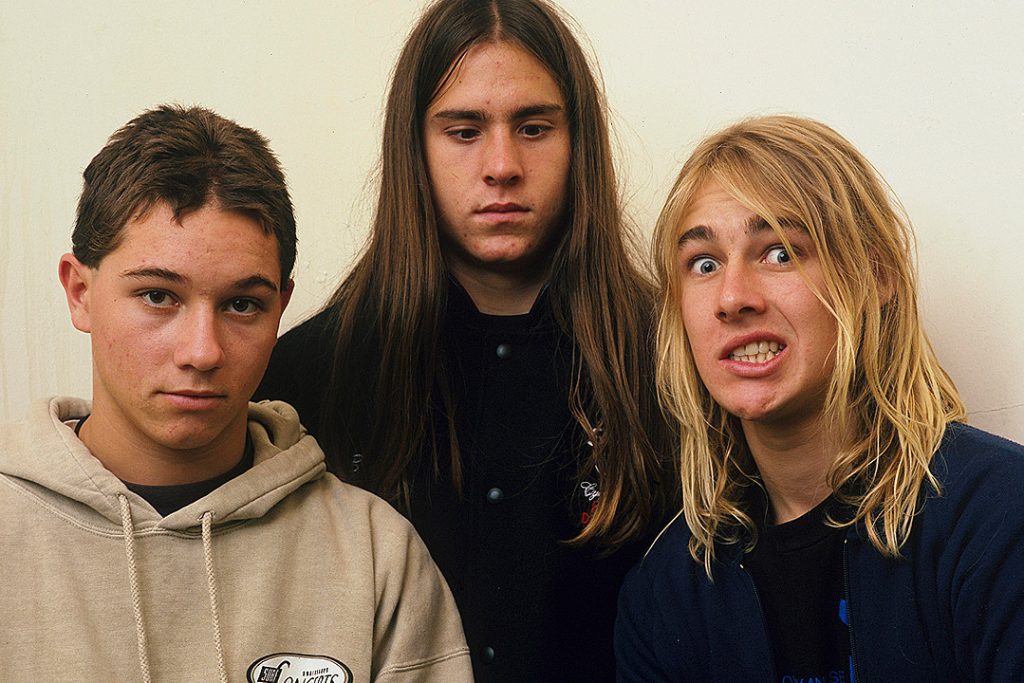

By the end of the touring cycle for 1997’s Freak Show, Silverchair were a broken band. All before their 20th birthdays, the Newcastle trio had gone through the wringer with the entire world watching — twice over.

The insurmountable pressure put upon them to live up to their own hype – by fans, by label executives, by their team — could well have destroyed the band entirely. The unrelenting saga particularly took its toll on Johns, who became depressed during the Freak Show tour and had his pent-up anxiety transform into a well-publicised bout with anorexia.

“Food was just the enemy,” Johns would later reveal in on Enough Rope. “I hated the look of it, the smell of it… if anyone talked about it, I’d leave the room.” At one point, Johns weighed in at under 50kg — nearly half his previous weight — and would often contemplate suicide.

His mental and physical instability also pored into his music, which was still being written in 1998 in spite of his setbacks. Even after the band had originally planned to take an extended break after Freak Show, Johns stuck to his creative process and saw it out to the bitter end.

From his standpoint, as has been established, writing music was out of need rather than want. It was a compulsion that drove him, often serving as a stand-in for therapy sessions. When he sings on this album, he sings from a place of anger, confusion and pain. Even at Silverchair’s angstiest and grungiest on Frogstomp and Freak Show, he still sounded like a despondent teenager with gritted teeth. On Neon Ballroom, that changed entirely.

Johns screaming “get up” over and over during the bridge of ‘Emotion Sickness’, is one of the single most unnerving moments in Silverchair’s complete recorded history.

He is spitting venom across track after track, reaching into a guttural rasp (‘Ana’s Song,’ ‘Dearest Helpless’) and the occasional banshee scream (‘Spawn Again,’ ‘Satin Sheets’) to drive home his innermost convictions.

Still being a 19-year-old, he’s prone to wrap up a lot of his thoughts and feelings in drawn-out metaphor or symbolism in the lyrics of Neon Ballroom — “No chance slipped away/Toddler training toys” may as well be the next “No more maybes/Your baby’s got rabies” in terms of deeper meaning. Having said that, there are moments of raw, unadulterated exposure on this album — Johns screaming “get up” over and over, seemingly at himself, during the bridge of ‘Emotion Sickness’ is one of the single most unnerving moments in Silverchair’s complete recorded history. That’s accentuated by its payoff: Johns culminating his desperate chant with the simple, devastating question of “Won’t you stop my pain?”

Johns has never sounded like this on record before or since, across any of his projects, adding further weight to Neon Ballroom‘s unique nature and idiosyncrasy. This is something he could have only written and performed at this very moment in time.

Another Point of View

At the time of release, not many were quite sure what to make of Neon Ballroom. As expected, it went to number one, and went double platinum — as did every Silverchair album ever released.

Reception over the band’s direction, however, was as mixed as the sonic palette of the record itself. Rolling Stone dismissed the album as “a young band going through its awkward phase,” while The AV Club backhandedly described it as “a collective step forward” in spite of what they saw to be “a few especially low points.”

A vital album with a true fighting spirit.

With 20 years of hindsight, however — not to mention eight full years of Silverchair being spoken of in the past tense — there’s a chance for those that may not have understood exactly where Neon Ballroom was coming from to reevaluate it under a new light. Consider that, when a lot of the criticisms were made about Neon Ballroom, it was from the viewpoint of being the most recent studio album for a still-active band.

In 2019, we view the album through the lens of the band’s entire canon and subsequent legacy — and it’s here that one is able to find an album that has survived against all odds; a vital album with a true fighting spirit that created its own light out of the darkest period in the band’s history.

Press play on Neon Ballroom, and see where it takes you after all these years. Here we go again, off into music-land.

David James Young is a writer and podcaster. Neon Ballroom was the first album he ever bought. Find out more about him at www.davidjamesyoung.com.