The Secret Anarchist Punk History Of Chumbawamba’s Hit Song ‘Tubthumping’

--

“I GET KNOCKED DOWN, BUT I GET UP AGAIN, YOU’RE NEVER GONNA KEEP ME DOWN”

It’s one of the most ubiquitous choruses of the nineties, a boozy chant of a song that, to this day, is instantly recognisable.

Chumbawamba’s ‘Tubthumping’ is one of those freakish one-off singles — the sound of a band consolidating all their best ideas around one song so anthemic and infectious that it turned out to be undeniable, never to be repeated and doomed to “one hit wonder” status.

Both now and then, it’s often seen as a novelty single — and in many ways, that’s understandable. It’s a rowdy anthem, ubiquitous in pop culture and pub alike, pummelled by repetition to the point of cliché. On either side of its three week run at the top of the Australian charts were ‘Barbie Girl’ and ‘Dr. Jones’, two similarly ubiquitous hits. With all due respect to Aqua, 1997 was a pretty frivolous time for pop music.

But under the surface is one of the strangest and most fascinating stories in pop music — a working class anthem purpose-built for chart domination by a collective of British anarchists who, fifteen years into their career, decided to try and play the system — and ultimately won.

Fuck The System

To understand the song, you need to understand the band’s history — all the way back to when they first formed in 1982.

A staunchly DIY group with post-punk influences, they lived together for years in a Leeds squat and were heavily involved in north England’s anarchist punk scene. One of their first songs was even released on a compilation by legendary punk collective Crass.

Even within that scene, they were agitators from the beginning. For one of their first recordings, they took aim at Oi! — an emerging style of punk favoured by skinheads and white nationalists — mimicking the style so effectively that they bluffed their way into an Oi! compilation. The song, under the pseudonym “Skin Disease”, involved them shouting “I’m Thick!” 64 times.

Soon, they started kicking against the orthodoxy and insularity of their own community. In a scene where even releasing a record on vinyl over cassette was enough to be accused of selling out, they began to drift away. Amidst the Thatcher-era political climate , they aligned themselves more closely with working class ideals, regularly playing benefits and picket lines, and getting involved with causes like the British Miners’ Strike.

As the late ’80s rolled into the ’90s, they grew further away from punk, but became heavily influenced by emerging genres that challenged authorities and conventions. The burgeoning rave culture was a huge influence as it spread throughout England, fuelled by illegal warehouse parties and in constant battle with the authorities. And soon after, sample culture allowed them a new way to subvert mainstream pop culture and undermine copyright law.

As all of these influences collided, the group’s reputation grew, and in 1997 they were offered a contract with EMI Germany. It was an offer that, on surface value, went against everything the group had stood for — after all, they’d recorded on a compilation years earlier called “Fuck EMI”.

But after fifteen years of provocation and political action, they decided to turn it into their most subversive act yet: mainstream success.

The Worm Turns

That history is important, because it helps us make sense of ‘Tubthumping’ — a song so strange and unique that, in hindsight, it couldn’t help but be a one hit wonder. From the verses’ undeniably 90s electronica and strange, shared vocals, to the song’s triumphant football chant of a chorus, ‘Tubthumping’ is the point where all of the band’s influences came together in one purpose-built, chart-topping smash.

But of course, it wasn’t just a big pop hit, and despite the song consisting of just a few repeated lines, the political manifesto under the surface went far deeper. In the album’s dense liner notes, ‘Tubthumping’ (along with all the other tracks) was paired with an extensive, eclectic patchwork of quotes and references, ranging from Malcolm McLaren, to McLibel, French graffiti and Baudelaire.

“The song was specifically designed to be an empowering anthem for a sidelined working class”

After all, ‘Tubthumping’ is British slang for political campaigning, and the song was specifically designed to be an empowering anthem for a sidelined working class. When put against the group’s backdrop of protest and activism, the chanted chorus of “I get knocked down, but I get up again/You’re never gonna keep me down” takes on a new resonance.

It certainly resonated, and we loved it the most. In Australia, it hit #1 for three weeks and eventually became the third biggest single of 1997. It also topped the charts in a handful of other countries, while in the UK it reached #2, and in the US it hit #6.

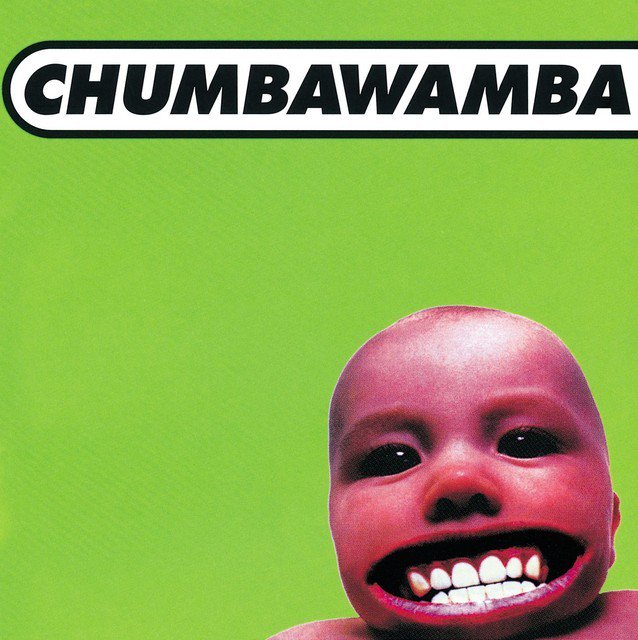

The ‘Tubthumper’ album cover

The gamble had worked. Chumbawamba, a collective of anarchists fifteen years deep into a strange career, briefly held the world’s attention — and they made decisive, bold use of it to champion their causes.

Take the 1998 Brit Awards, for example. In one of their first major television appearances, they performed ‘Tubthumping’ against footage of British protest movements, surrounded by the red and black flags of rebellion and anarchy, and clad in jumpsuits with bold phrases like “Sold Out”, “Shift Units”, and “Label Whore”. And throughout the song, they incorporated the phrase “New Labour sold out the dockers, just like they’ll sell out the rest of us”. It was a bold move – Labour had recently been elected after years of conservative rule, amidst plenty of popular support.

But the most infamous moment came later that night, when vocalist Danbert Nobacon ambushed then-deputy Prime Minister John Prescott at his table, dumping a bucket of ice cold water on his head mid-event.

In the press, they were similarly controversial. Virgin stores started selling the album from behind the counter after vocalist Alice Nutter told a talk show that fans who couldn’t afford the album should steal it from chain stores. In Melody Maker she was at her most militant, seemingly advocating for violence against police.

Licensing was another form of protest — the band very publicly turned down a $1.5m offer from Nike to use the song in a World Cup advert. Several years later, they would accept USD$70K from General Motors for use of another of their songs in an ad — only to immediately donate it in full to activist groups, to be used in a campaign against, you guessed it, General Motors.

These were just a handful of the most well-know incidents from that brief period when Chumbawamba were one of the world’s biggest bands, and across a thirty-year career, there’s so many more examples to be found. But within the mainstream, Chumbawamba quickly faded, doomed to one-hit-wonder status as their eclectic, unpredictable music stylings failed to bother the charts any further.

But perhaps that was by design. In ‘Tubthumping’, they’d managed to write an empowering working-class anthem and push their ideas to a global audience in a way that surely couldn’t be sustained — and seemingly wasn’t designed to.

Nonetheless, twenty years later, it’s still one of the strangest moments in pop music, and one that likely will never be repeated.

—

Adam Lewis is a music booker and enthusiast from Sydney. Follow him on Twitter.