Girls To The Front: Incredible Photos Of Australia’s Fiercest Female Punks

Get to know Liz Ham's 'Punk Girls'.

“It’s another all-male tour preaching equality/It’s another straight cis man who knows more about this than me/It’s another man telling us we’re missing a frequency” drawled Camp Cope’s Georgia Maq on their November release ‘The Opener’, rounding out a banner year for homegrown, female-fronted punk (see also: the rise and rise of Amyl and the Sniffers, Boat Show winning Bigsound, Sad Grrrls Fest expanding to a three city event.)

Of course, feminist punk is nothing new to Australia. Just ask Liz Ham: since coming of age during the glory days of ’90s Riot grrrl, she’s been front-and-centre of Australia’s punk scene, first as a punter and later as a photographer. Five years ago, that passion — combined with concern over how women had been written out of punk history — inspired her to start photographing and profiling Australia’s female-identifying punks. The project was originally intended to be a zine and eventually wound up as a 200-page, hardcover, high-gloss book.

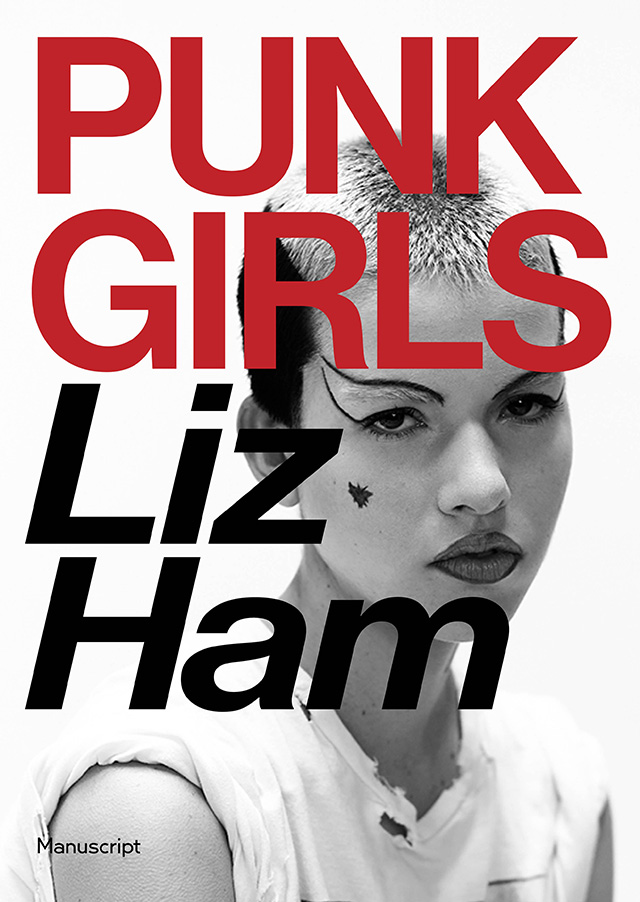

That book — titled Punk Girls — is out now, and features both portrait and candid photos of Australia’s GNC and female punks on stage, on the street, at gigs and in studios. To celebrate its release, we spoke to Liz Ham about twenty years of pushing to the front.

Can you tell me about what inspired you to start the Punk Girls project?

I started about five years ago. I’d been spotting more and more really amazing looking people on the streets in my neighbourhood — I live in Newtown [in Sydney] — and I was also looking to do a large format portrait project.

So I thought it would be nice to combine some fashion images I’d already been working on, which were very much around the idea of women in punk, with new portraits I could take of these women. I wanted to somehow be able to tell their stories, and, at the end of the day, make a little fanzine or something quite lo-fi out of it.

But the project escalated and got a lot bigger than a fanzine, and I ended up doing over 100 of these formal portraits. Then I did a whole bunch of documentary style images, as well as the fashion-based imagery, and the end result is like a book which is over 200 pages. I think at least 200 women are represented in the book.

But the main impetus for me when I first started this project was that I felt there wasn’t anything else really like it out there, even on an international level. Especially contemporary images — there’s a lot of the old photography that we’ve all seen, from the ’70s and early ’80s, of the original first wave punks. But, even then, I couldn’t find many stories or much information about the women of that time.

I noticed that a lot of their stories were being — well, sometimes they were erased — but, a lot of the time, just not acknowledged and marginalised, pushed off to the side. Once I got wind of that, I thought, “Well, we’ve got to make a change here. We’ve got to get these stories and these faces out there.”

I was going to ask if you thought that women had been written out of punk history a bit, and it sounds like yes, you did.

Yeah, definitely. I mean, when you look at something like punk history, it’s fascinating that it started in this wonderful, really liberated place where people wore whatever they wanted and really pushed the boundaries.

But with gender and in a lot of other ways, it was an incredibly conservative time. When you read Viv Albertine’s book that came out a couple of years ago [Clothes, Clothes, Clothes. Music, Music, Music. Boys, Boys, Boys.: A Memoir], she talks about being stabbed in the street by random strangers because of the way she looked.

Something happened after that with the American hardcore scene and women were pushed away even more — just really not having any place at the front of those crowds. When you think about American hardcore bands, there were very few women really involved — so thank god Riot grrrl came along at just the right time and finally allowed all the girls to come to the front.

I think it allowed women — specifically in my generation, because I was a teenager when that happened — to really feel, for the first time, that I could actually go stage front, stage dive, look how I wanted, scream and shout, not act like a good girl, do whatever I wanted.

So was Riot grrrl a lifeline for you in your teens?

Oh, yeah, for sure. Definitely. I mean, I was loving that music. The music itself was so powerful, and I feel like listening to Babes in Toyland, Bikini Kill and Hole just completely got me through, especially the last few years of high school. But it just was having that outlet — that really wonderful, physical outlet of going out and of being truly expressive, and being with the girls. It was so unifying, and it was just so liberating and so fun.

When I think of Riot grrrl, I associate it mostly with the US. Was it big in Australia as well?

Yeah, I feel like it kind of was. We didn’t have the same number of bands, and sadly I don’t think many of those American bands came here — although Sleater Kinney toured and I think they even lived here for a while. We had Fiona Horne who was in Def FX — she had a great band called The Mothers, so I feel like we did have pretty good little scene here. I was also under 18, so I couldn’t get out to heaps of gigs, but I would totally try to sneak into a few.

How has the punk scene changed over the past few decades, since that Riot grrl point?

I feel like even the definition — the word punk — has changed. When people say “Punk is dead,” they’re referring to a very specific moment in time. They’re probably talking about that very first wave of punk, and maybe that is dead — and maybe that’s a good thing, because there was a lot of misogyny and racism within that scene.

And the way I use the word “punk” is really broad as well. To me, it means a lot of different things, and it’s very much about freedom. Mostly, now, I feel like punk has evolved to be this incredible space that offers a very strong feeling of community and support. I feel like it’s become a really intersectional space and it’s really tied up with feminism, especially third wave feminism.

So, for me, punk is about just really saying, wearing and doing what you want. It’s also a space where people need to be very politically driven and really nurture each other. It’s like a really lovely, unifying word.

And that focus on intersectionality, do you think it’s made punk shows safer spaces? Do you feel like they’re a lot better now?

I do, yeah. Some gigs I’ve gone to have been very, very masculine and very intense; sadly, we’ve heard all these stories about women having horrible things happen to them in the mosh pit, getting pissed on and horrendous stuff.

But I don’t necessarily think those things are happening at the punk shows that I’m going to. A lot of the shows I go to are very much intersectional places, they’re incredibly inclusive — so there’s a lot of different factions within punk. But, yeah, I do feel like it’s become a much, much safer space in general for all people. Which is wonderful.

So what gigs did you go to for this project?

Oh god, heaps. Lots of different types of shows as well — like DIY shows in warehouse spaces in Sydney and Melbourne, which were always really great, because that sense of community is really, really strong. It’s often a pay-what-you-can kind of policy, and food and drinks are usually provided at a reasonable cost. It’s really about just making sure that everyone’s able to be part of it.

And then some very small shows, all the way through to the bigger shows like when Against Me! came through. I’ve basically been gigging since I was about 14 and I haven’t stopped, so this has just been this great opportunity for me to just keep doing what I do, but having fun and providing and making a body of work at the same time.

There’s photos in the book of artists like Georgia Maq from Camp Cope, and Isabella Manfredi, and Nai Palm. What about those artists appealed to you as subjects?

Nai Palm is just incredible as a performer and on a personal level as a human. She is so… it’s hard to even put it into words. To me, she seems quite otherworldly. She’s also incredibly gifted and an absolute genius. So all of those things really drew me to her specifically.

Nai Palm also introduced me to her really dear friend, Cosi, who was in the band Mangelwurzel, and now has Jaala. It’s been really wonderful that one person generally sends me onto another person, and then I kept on being able to expand my network of subjects that way.

I was following Camp Cope from very, very early on in their career. I took that photograph just at a gig that I was at; I am still yet to meet the band. I would absolutely love to meet them and photograph them properly, but their politics and their incredible music really drew me in. They’ve been amazing as well at the very forefront of trying to stand up against abuse at gigs, and also the inequality within the music industry. They’ve been incredible with that.

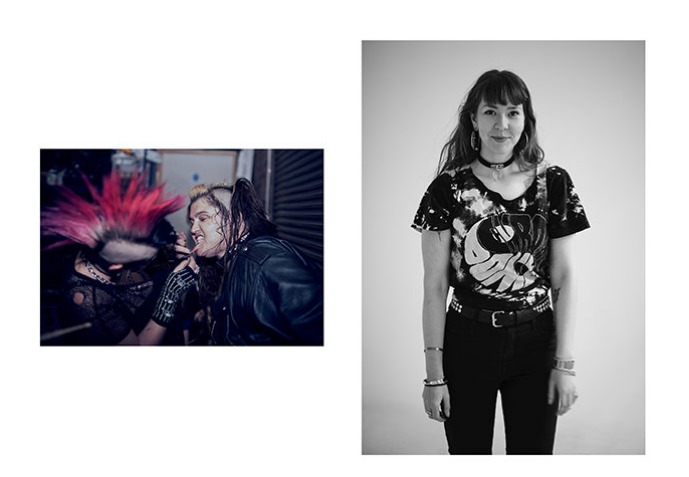

Isabella Manfredi is a friend of a friend, so that photograph happened on the back of a shoot that I was doing for Ollie Henderson’s Start the Riot label. We were just doing a little photo shoot with all of her friends in the t-shirts and Isabella turned up, which was awesome, because I just love her music as well. She’s incredible, and she’s a really strong, fantastic role model in the music industry.

Camp Cope’s Georgia Maq

How did you find the “regular people” that you took portraits of, and what made them stand out to you?

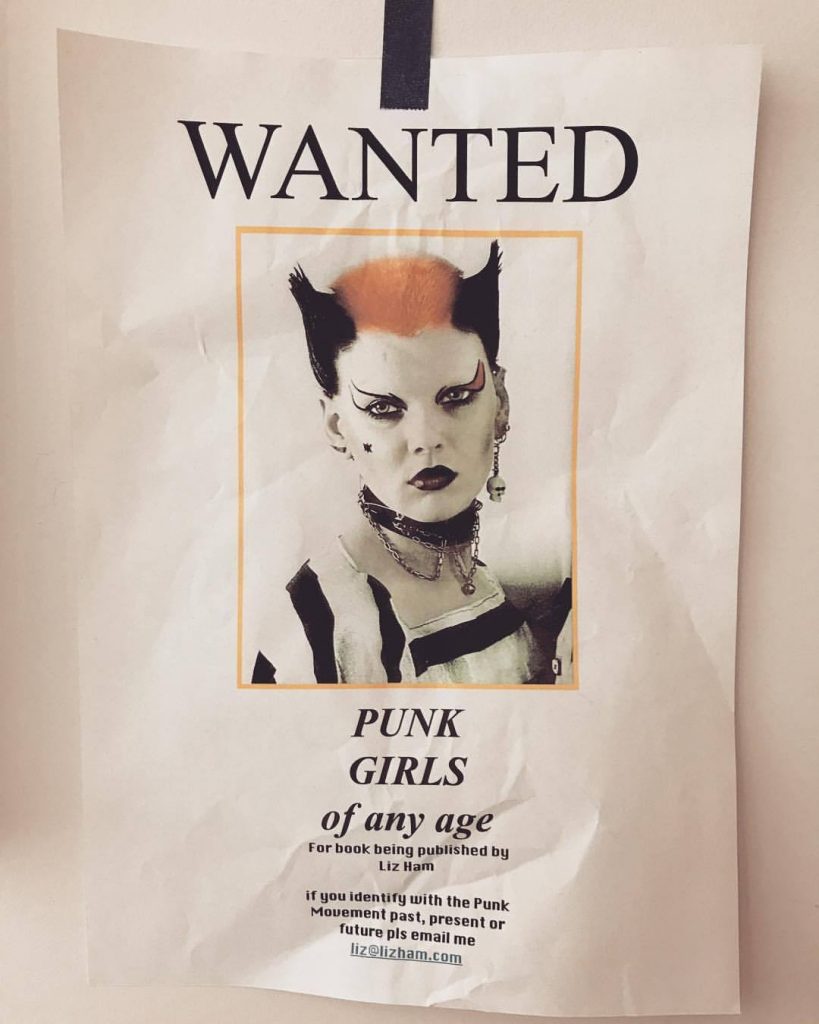

The more formal portraits that are in the book mostly came about because I printed out a flyer and stuck it up all over Newtown.

I took them out to gigs and, sometimes, left a pile in the ladies bathroom. They basically just said — “Wanted. Punk girls of any age for a book being published by Liz Ham,” and all I asked was that they identified with the punk movement past, present or future. As the book developed, I also changed that to include female-identifying people.

People came to me in the early stages of the book, and I would take their portraits, often in my studio. Sometimes they’d bring a friend, or sometimes they’d telephone to get in touch, and then it just started to snowball from there. As I got going with the project, I’d sometimes handpick certain people that I knew of, or had met out and about, or people in bands that I just thought were incredible, and do some formal portraits with them as well.

So it was a very organic process, really. I could just keep going at it for the rest of my life. It’s one of those things. You can’t even put an end date on something like this. You can certainly say, “Well this book is now big enough. 200 pages is big enough,” but the project will continue, absolutely.

I read in the book that you asked your subjects to fill out a questionnaire on what it meant to them to be punk and a girl. What were some of most interesting responses you got?

It was really, really fascinating. The most interesting part of [the project] for me was the data collection. I specifically really wanted to find out about what the underlying reasons were that people found punk, how they felt being in that scene, and how they felt as a female in that world.

The number one thing for me was the word “freedom” just keep popping up over and over and over again. Liberation was the main feeling that women get from punk. It was also really fascinating just to see some people would write really short, sweet answers on the spot and be cool doing that, and other people would want to really give it a lot more thought and take it home, then send it back to me.

Some of those ones that got sent back are really beautiful, really lengthy, amazing, amazing pieces of writing with stories and anecdotes that are just phenomenal. I think down the track, these stories and questionnaires are probably going to be archived in an institution here in Sydney, but also online. I’d like to start up a portal where the photographs and the Q&As can be alongside each other, because there’s some wonderful writing in them.

That sounds great. You said in the interview at the back of the book that you were intrigued by early punk photos of The Slits, where the women in them weren’t trying to look pretty, or available, or sexy; just raw. Is that what you went for with your shots?

I guess so, but it also depended on how people present themselves to me. With all the portraits, I wouldn’t augment any of those images at all. Basically whatever somebody turned up in on the day, what personified punk to them, that’s how they would be photographed. It’s was very much their directive.

And, I guess, punk has so many different outward expressions. Like, punk can be super sexy and really fetishistic, or it can be incredibly androgynous and non-binary. It’s just really an outward expression of how somebody feels inside.

I think it was very important for me not to alter the images of these women, and not to Photoshop them, because I think we’re so oversaturated with that kind of puerile [imagery]. What is so beautiful about looking at those images from the past is that we’re really looking at a reality. We’re not looking at a polished magazine image, we’re looking at a gritty, real image of a woman. Those images are amazing and they really stand the test of time.

You dedicated the book to Maureen O’Brien, and her portrait is also featured. Did you want to tell me about her story?

Maureen was one of the subjects that I met in Melbourne. Everyone kept saying, “You’ve got to shoot Maureen. You’ve got to shoot Maureen.”

So, Maureen started the now infamous Melbourne Punk Pub Crawl, which happens on a public holiday — I think it’s on the day of a very big football event in Melbourne, which being a very unsporty person, I can’t even tell you. Sadly, I’ve never been to the Punk Pub Crawl, but she started that a very, very long time ago. Gosh, I think it would have been in the ’80s.

She also used to be a promoter. She used to help a lot of bands tour Australia — I guess she was one of those glue type people in Melbourne that really nurtured that scene early on. Sadly, she passed away last year.

Maureen O’Brien

But Maureen was quite an outcast, she was living in a housing commission [home] and things hadn’t gone very well for her. It was quite heartbreaking. But she would often write to me and send me poetry, emails and text messages, so I ended up with this beautiful collection of all of her thoughts and her creative outlet, which I’ve collected and I’m passing onto her family.

So when I heard that she’d passed away, the book absolutely had to be dedicated to her, without a doubt.

And you also mention in the book that there are great punk scenes in places like Canberra, which is where I’m from, and Wollongong and Newcastle. Why do you think that punk sometimes flourishes outside of major cities?

It’s very interesting, isn’t it? I reckon that because Sydney or Melbourne are such a big community of people, you end up with lots of smaller cliques, and tinier little microcosms of people.

But when you’re in those slightly out-of-town places, there might be a whole bunch of subcultural people — you could have some people that look more skin, or people that look more crust, or some that are more metal. But they don’t have as many things to go to, so they find each other and so you have these really flourishing scenes that are actually super diverse at the same time — which is really, really cool. Did you find that in Canberra?

I was thinking before I called you about what the answer to that question was, and I couldn’t really work it out, apart from maybe that being a small city lends itself to that sense of that community more.

Yeah, I think that’s exactly true. I haven’t really been to Canberra for this project, but I’ve heard a lot of great things about the Canberra scene, and I know that it’s always been pretty strong down there. Also, it’s a good university town. Where you find universities, you often find some really great, flourishing scenes. Same in Newcastle. Same in Wollongong.

—

Katie Cunningham is the Editor of Music Junkee. She is on Twitter.

—

Punk Girls by Liz Ham is out now via Manuscript. You can buy it here.

—

All photos by Liz Ham.