Miley Cyrus Is (Literally) Returning To Her Roots And It’s Boring As Hell

You can track Miley Cyrus' entire career through her hair.

I was too old for Hannah Montana. By the time Miley Stewart was donning her Montana drag and singing about “The Best of Both Worlds”, I was embracing underage drinking, learning to drive, and going through my alternative teenage phase where any and all pop music was crap, and the only bands worth listening to were Broken Social Scene or Tegan and Sara.

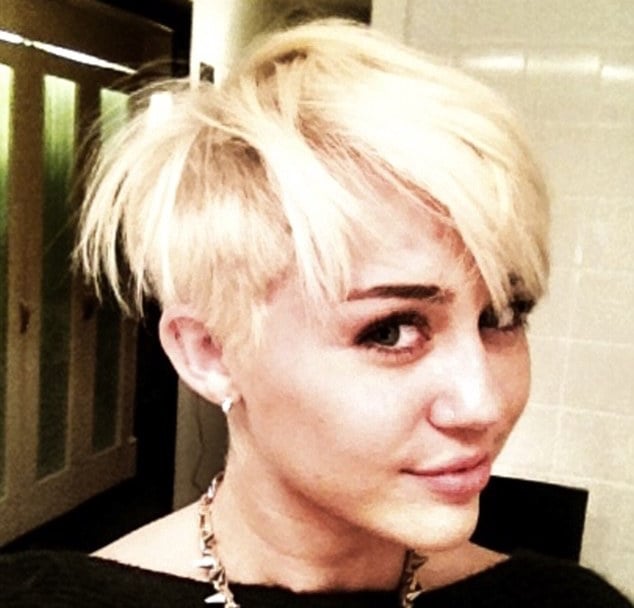

My infatuation with Miley Cyrus began much later, and can be pinned to a rather specific point in time: August 2012, when Miley — like I had two years earlier — ditched her long brown hair in favour of what was often described as a ‘lesbian haircut’.

In the ensuing years I have kept close tabs on Miley but, more importantly, I have kept close tabs on her hair. Queers know all too well that your hair says some pretty wild things about you. This is why I knew, in January, months before ‘Malibu’ would be released, that Miley Cyrus was planning something incredibly boring for us.

Miley Cyrus’ career has always been written in the hair — from when she needed to don a wig to perform as Hannah Montana, through her appropriation of queer and black culture in the Bangerz and Dead Petz years, and now, with ‘Malibu’, as she returns, quite literally, to her roots.

August 2012 — Zero AH (After Haircut)

When Miley cut her hair in 2012, it was a big deal. But, in retrospect, this moment was more pivotal than even the tabloids could’ve realised. The Daily Mail wrote at the time that her hair wasn’t exactly a “bridal hairdo”, and noted the considerable backlash she received, but it wasn’t until later that the weight of this haircut was realised.

Ruby Rose, is that you?

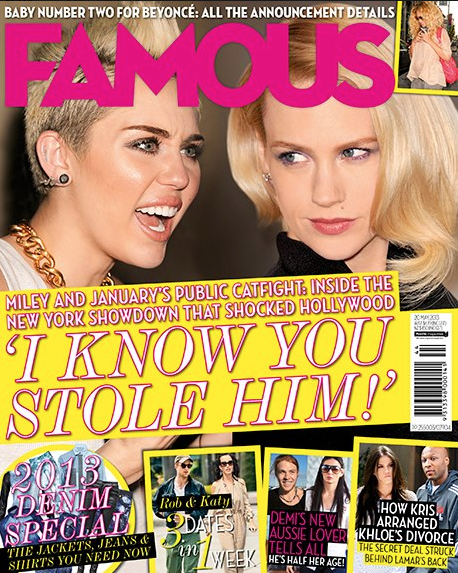

My gaydar was pinging — and not just because it largely relies on queer stereotypes. The now out-of-print gossip magazine Famous reported that this “radical” haircut was an obvious display of her bisexuality and — as gossip magazines are wont to do — claimed that, according to a “source”, Miley had cheated on then fiancé Liam Hemsworth “with another woman!”

If you have spent as much time closely examining the tabloid press coverage of Miley Cyrus as I have — in 2014 I mined 734 editions of Australian gossip magazines to find all 321 stories about Miley (for uni, I swear) — you’ll begin to see a pattern emerge from August 2012 onward. These are the “After Haircut (AH)” years.

Before Haircut (BH), Miley’s indiscretions were often put down to youthful frivolity. Smoking salvia at her 18th birthday? Smoking a small amount of weed and being condemned by her father? Well, isn’t that what every child star does? She’s no Lindsay Lohan, after all (when these remarks are made, you can almost see the magazines crossing their hearts and praying to the heavens).

AH, the tone of these magazines takes on something far more sinister. This, I believe, is in no small part related to the evil heathen connotation of her haircut: bisexuality. Was Miley actually becoming the new Lindsay Lohan?

Gossip magazines — like much of mainstream society — rely on a particular narrative around chaste femininity for young white women (it’s a different story, typically one of over-sexualisation, for young black women), and they gleefully report on any transgression. In their view, Miley Cyrus’ shedding of her hair was a shedding of her femininity. It led to literally months of continual speculation over the state of her heterosexual engagement to Liam Hemsworth.

Famous cover, May 20, 2013. January Jones’s luscious hair vs Miley’s crop (also, Beyonce’s second baby? In May 2013?!)

When her engagement ended in September 2013, tabloids were able to finally report the narrative they’d been waiting for: the downward spiral of a woman who’d failed that chaste white femininity. Miley Cyrus joined the ranks of those who came before her: Anna Nicole Smith, Amanda Bynes, Britney Spears, and of course, Lindsay Lohan.

The Bangerz And Dead Petz Years

For Miley, 2013 was a year of hypersexualisation and a heap of weed. But alongside the lesbian haircut and the breakdown of her relationship with Hemsworth was a far more sinister side to Miley’s newfound rebellion: her appropriation of black culture.

Writing at the release of ‘We Can’t Stop’ (which had its fourth birthday over the weekend — time really fucking flies), Dodai Stewart wrote for Jezebel about Miley’s desire for a song that “feels Black”, and the track’s abuse of black bodies and black culture for profit. The entire Bangerz era reeked of appropriation: from the gold grill, to the twerking, to spanking her black back up dancers on stage, Miley was styling herself black, and it was making her money.

But Miley wasn’t done with using minority cultures there. She was also, in ways far more subtle (and less damaging) using queer culture. The appropriation of queer culture (if we can call it that) is much harder to pinpoint because Miley did — and still does, to some extent — identify with aspects of queerness. She has had relationships with women (who remembers her and Kristen Stewart’s new beau, Victoria’s Secret model Stella Maxwell?!).

“Swinging into GiRLTHING and seeing five of your exes hanging out together be like–”

Whether you could call it “appropriation” or not, throughout these years Miley was certainly “employing” queer culture. There was the haircut and the Doc Martens circa ‘Wrecking Ball’ (where she looks like she could’ve stepped straight off the stage at a GiRLTHING Jelly Wrestling match), but there were other signs too. There’s the obvious sexual connotations of that tongue (which can be read in many different ways), or the even more obvious sexual connotations to her preference for fisting, or the perhaps too obvious stage antics during the Bangerz tour.

Throughout these years, Miley became more synonymous with unicorns and glitter than a gay pride parade, and she would often wear the black and queer cultures simultaneously.

“It’s here that Miley’s use of queer culture begins to feel less authentic, and more like she’s borrowing it for the sake of trying to appear as weird as possible.”

During the Bangerz years, I enjoyed Miley’s hypersexualised queerness, because it felt authentic. I couldn’t forgive her “ratchet” antics, but I relished the queerness because I liked the way she disgusted people with it. When she proudly displayed her hand of Adonis, NW told their audience it was a “sex device specially designed for fisting enthusiasts. Ew!” Miley seemed happy to flaunt her sexuality, but importantly, it was hers, and so she had the licence to.

Looking at Dead Petz retrospectively, it’s here that Miley’s use of queer culture begins to feel less authentic, and more like she’s borrowing it for the sake of trying to appear as weird as possible. Interestingly, it’s in these years that her hair begins to be less queer, and far more black.

For much of the Dead Petz tour, Miley sported fake dreadlocks, and dressed as a unicorn wearing a strap-on. Now, her appropriation had inverted — her hair was black, and her back up dancers queer (and black).

When she first began to sport this hair, her appropriation was called out (thanks Nicki Minaj), but soon she, and it, began to fade into obscurity. The public couldn’t seem to handle just how weird, and perhaps inauthentic, Dead Petz was. It no longer felt like Miley’s strap-on was a celebration of sexuality; it felt much more like a grab at attention for her failing album tour.

Returning To Her Roots

In January 2017, Miley posted a selfie, just weeks before her media blackout prior to the release of ‘Malibu’. Here, her hair portends the direction her career was about to take: “goin back 2 muah rootz”.

Cut to a few months later, and we have the Miley of ‘Malibu’, the girl who has discarded black culture like an old newspaper, publicly regrets the antics and [queer] aesthetic of ‘Wrecking Ball’, and whose return to wholesomeness has been so aptly described as “creepy”.

In ‘Malibu’, Miley is showing us that, like her hair, she’s grown out of her old self. In her regrowth is her literal return to her roots, in the brunette/bleach blonde colour mix is the unification of Hannah Montana and Miley Stewart. Miley Cyrus is now the all-American girl Hannah Montana always was — she’s the symbol of chaste, white, femininity the gossip magazines want her to be.

Snooze.

She’s telling us this, abundantly clearly in the white clothing that cleverly covers her tattoos; in her discarding of black culture, of stoners, of hypersexuality and everything her Bangerz and Dead Petz era personified; in the boring, vanilla, snorefest that is the song itself.

It’s easy to see why Miley chose to use black and queer cultures the way she did. She was rebelling from her younger years, and what’s more rebellious to a teenager from Tennessee, in the heart of the bible belt, than hypersexualised versions of blackness and queerness?

To see Miley discard these cultures and their haircuts is both disappointing, and satisfying. The fan in me was disappointed as ‘Malibu’ proves that we were just pawns in her rebellion all along, and there was little authentic about her use and abuse of queer and black cultures — except the financial gain she made.

But it’s also deeply satisfying, because without black and queer cultures, Miley is utterly white, utterly chaste, and utterly, utterly boring.

–

Lucy Watson is the online editor at Archer Magazine, and a freelance writer. She is completing her PhD on how queer people respond to celebrity media at the University of Sydney, and likes to consider herself Sydney’s leading Miley Cyrus expert. Like Miley, you can track her life stages through her hair. She tweets @lucyj_watson.