Revolutionary Road: George Miller’s Subversive ‘Mad Max’ Saves Action Cinema

Yes, the film passes the Bechdel Test. But to see the film’s triumph as being solely that it contains female characters who talk to each other is to grossly underestimate its revolutionary nature.

Having arrived at my 1997 high school debutante ball in a cheez-orange HT Monaro GTS 350 pumping Rose Tattoo’s We Can’t Be Beaten, I feel uniquely qualified to tell you that Mad Max: Fury Road – which opens in Australia today — is a holy-rolling hoon sermon shouted from the top of Mt Panorama to the true believers.

George Miller’s paean to car culture is evident in the deathly earnest “V8s” prayer hands that Immortan Joe’s War Boys raise to their leader, and in the sublime idiocy of The Doof Warrior’s flame-spewing electric guitar, and in the Bullet Farmer’s goddamned Valiant Charger with a Merlin V8 on tank treads.

But despite all the flaming twisted metal and heavy riffing, Fury Road’s most explosive element might be its keenly subversive heart.

In a landscape that exists somewhere on the same spiritual plane as The Road Warrior, Max Rockatansky (a soulful Tom Hardy) is stolen into the nightmarish Citadel of Immortan Joe (Hugh Keays-Burn, the original Toecutter): a despot who controls the water supply and whips his War Boys into a kamikaze frenzy with the promise of eternal glory in Valhalla. A universal donor, Max is strung up to serve as a “blood bag” for one of Joe’s ailing War Boys, Nux (Nicholas Hoult), who — like most of the Citadel’s residents — has been left bubonic by the apocalypse.

When Imperator Furiosa (Charlize Theron) is tasked with leading a guzzoline-fuelled convoy to neighbouring Gastown and Bullet Farm, she instead escapes with Joe’s wives (Rosie Huntington-Whiteley, Riley Keough, Zoë Kravitz, Abbey Lee and Courtney Eaton), “breeders” kept in luxurious bondage in the non-consensual hope that they might bear him a viable heir. Soon enough no fewer than three war parties (from the Citadel, Gastown, and the Bullet Farm) are in hot pursuit of Furiosa’s War Rig, including Nux’s Deuce Coupe, with blood bag Max strapped to the hood like the Spirit of Ecstasy. From there it’s roughly two hours’ worth of glorious insanity; as Nux cries at the wheel of his war machine, “OH WHAT A LOVELY DAY!!”

Full Of Sound And Fury, Signifying Everything

Much like the Grand Old Duke of York, if he were marshalling at Calder Park, Miller drives his war parties to the top of the map and drives them down again: plot, in the Save The Cat sense, is in as short supply as water here, which only serves to make Fury Road all the more thrilling.

This is action elevated (or lowered?) to an elemental level; as though Miller has taken the expected excesses of modern action filmmaking and distilled them into something approaching transcendence. Indeed, it feels as though Fury Road could kickstart an era of “existential action movies”, much like the rise of the existential western at the turn of the century.

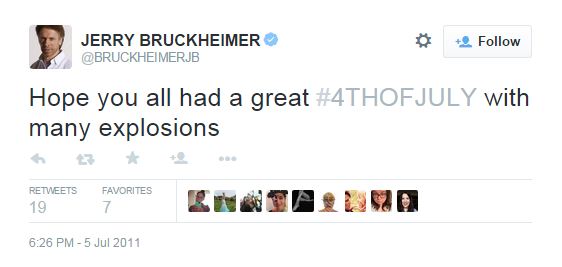

Happily, where existential westerns depended on subverting the sweeping vistas of John Ford and co. by way of meaningful glances and Jonny Greenwood scores, the existential action movie — if Fury Road is any indication — somehow manages to subvert the last twenty years of action idiocy by adding even more explosions.

Miller’s insistence on practical effects for the bulk of the action shots pays off: Fury Road, for all its mind-bending action, is the realest-feeling thrillride in years. He gives audiences what they think they want (rear-axle flips in slow motion) then follows it up with what they didn’t even know they wanted (SeaChange’s John Howard as the porcine and nipple-pierced People Eater in a stretch Merc covered in high-end car grilles).

The spectacle is aided by vehicle designs that make the original trilogy seem like an auction of fleet rentals: chief production designer and art director Colin Gibson’s demented armada of souped-up Franken-rods beggars belief. And, keeping things strictly Australian New Wave, the spine-covered vehicles favoured by desert nomads the Buzzards are a charming nod to the eponymous spiky VW Bug of Peter Weir’s Cars That Ate Paris.

Calls for stunt work to be recognised by the Academy should reach fever pitch upon this film’s release; if second-unit director and stunt coordinator Guy Norris doesn’t get an Oscar, he should at least receive a knighthood.

Action Blockbusters: No Longer The Exclusive Domain Of Young Men

Critics of a certain vintage have taken great pleasure in noting that Miller and cinematographer John Seale are both 70 years old — the barely veiled subtext, given the film’s thrilling action sequences, being, “Whoa! Way to go, granddads!”. The delicious irony here is that that’s the point: Fury Road works precisely because Miller and Seale inject it with the wisdom of their combined years.

A wunderkind couldn’t have made this film (Miller was already a grownup when he made his debut with Mad Max), and wouldn’t have had the guts to stick with tracking shots instead of a frenetic post-Matrix cut-’em-up; editor Margaret Sixel favours an almost languid pace during some scenes of destruction, amping up the dreamlike quality. Much like Herzog’s and Godard’s recent adventures in 3D, Mad Max has the fearlessness of a filmmaker who cares only to double down on his specific creative vision.

There’s a fearlessness, too, in using a ripsnorting demolition derby to deliver both an environmental cautionary tale, and a treatise on the abuse of women.

The first point shouldn’t be a surprise to anyone familiar with Miller’s astounding Happy Feet, a blockbuster whose environmentalist credentials were broadcast at about the same volume as James Cameron’s Avatar. The true message of Happy Feet wasn’t “dance to the beat of your own drum”, but rather a warning about the dangers of overfishing, transmitted via Busby Berkeley-esque routines to Beach Boys and disco songs. Similarly, the stark reality of a world without water is, for all the moments of post-apocalyptic gore and vehicular decapitation, the true horror of Fury Road.

And on the second point, it’s not really even Max’s story: rather, it’s Furiosa’s, her own tale of redemption and recovery from abuse mirrored in the lives of Joe’s wives. (Miller has more or less confirmed that a sequel would focus on her.) The characters who serve to populate her origin story, the film’s surprising twist, are the most exciting contributions to the action genre in years.

Charlize Theron as Furiosa with (L-R) Abbey Lee as The Dag, Courtney Eaton as Cheedo The Fragile, Zoe Kravitz as Toast the Knowing, and Riley Keough as Capable.

A number of reviews have made giddy reference to Fury Road’s Bechdel Test-passing credentials, but to see the film’s triumph as being solely that it contains a number of female characters who talk to each other is to grossly underestimate its revolutionary nature. Yes, this is a film with no shortage of awesome female characters, but it is also a wildly mainstream action tentpole where old women, fat women, and people with disabilities extensively populate the screen without fanfare. They are not “permitted” to appear by way of focus group lip service, or to provide edgy colour and movement; they just are.

In this way, Miller’s dystopian vision turns out instead to be the wildest filmic utopia in decades.

–

Mad Max opens today in cinemas around Australia.

–

Clem Bastow is an award-winning writer and critic with a focus on popular culture, gender politics, mental health, and weird internet humour. She’s on Twitter at @clembastow