A Love Story With Taylor Hanson: How I Found Queerness In Hetero ’90s Pop Culture

Back then you had to dig for hidden subtext.

As a teenager in the ‘90s, there wasn’t much choice of queer celebrities to crush on. I can’t help but envy all the queer millennials who have celebrities like Cara Delevingne, Ruby Rose, Demi Lovato, Miley Cyrus, Keke Palmer, Laverne Cox and Kristen Stewart to help them figure out their sexuality and gender identities. They even have queer YouTubers and vloggers like Ingrid Nilsen, Hannah Hart and Troye Sivan, to clarify things further.

Back in the olden days, of course, things were different. Young queer people had to take what they could get. Ellen Degeneres and k.d. lang were obvious celesbians to develop crushes on, but they were decades older — ew, amiright? Just kidding, I love them — and I was after someone to be my teenage dream.

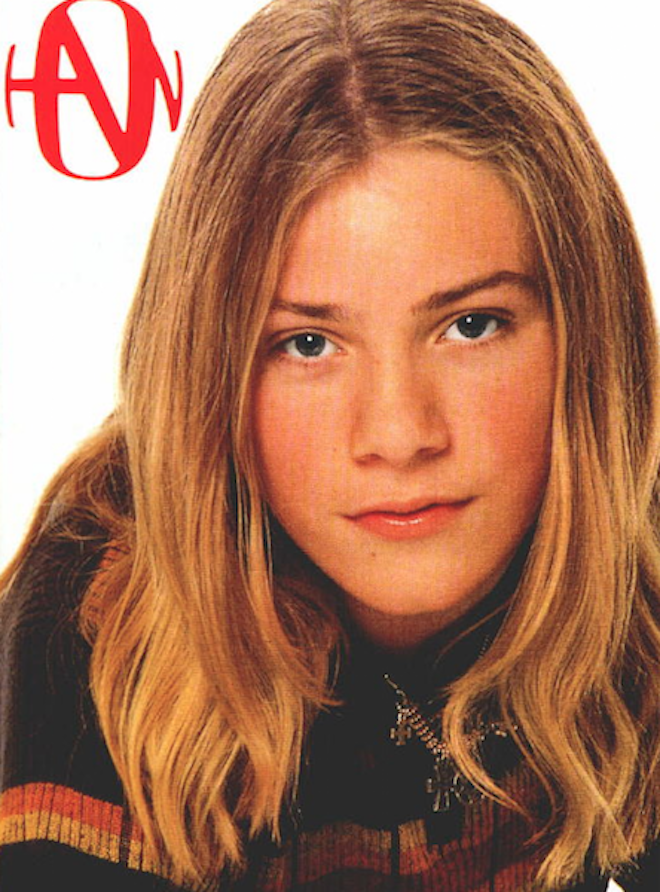

I found mine in 1997. This lovely young blonde, for those too young or old to recognise him, is Taylor Hanson. He is — don’t hate me, Zac and Ike fans — the most vocally talented in the group Hanson.

This is Taylor.

I was 13 years old when I developed an obsession with Taylor, which lasted for longer than I care to admit. I noticed early into my obsession that many of my friends did not feel the same way and they were more vehement about Taylor than they would usually be when we disagreed over a crush. “He looks like a girl!” one of my friends exclaimed when she saw the video clip for ‘MMMBop’ on TV. “Gross!”

I disagreed with her at the time, but now I look at teenage photos of Taylor with mixed amusement and befuddlement. How could I not have seen it? I was, in hindsight, clearly attracted to his ambiguous gender and the way he didn’t prescribe to traditional notions of masculinity. I liked the Hanson brothers for keeping their hair long, and features ‘pretty’, despite the teasing and judgement they received. Some people view the negative reactions to the Hanson brothers’ long hair and feminine features as homophobic and transphobic.

All of this makes me wonder if I loved Taylor as much as I did because he looked like a queer woman, as I had so few out role models at the time. Last year, Saturday Night Live’s female cast members sang ‘First Got Horny 2 U’, a hilarious ode to their early crushes. Kate McKinnon, who recently sent queer hearts soaring as Holtzmann in Ghostbusters, sings about “Taylor Hanson’s lips, and his long blond hair, the most gorgeous woman anywhere” and explains that “and that’s how I could tell, that I was gay as hell.”

I couldn’t tell that I was queer as hell. Whenever I heard Taylor sing ‘I Will Come to You’ or ‘Thinking of You’, I couldn’t help but dream that he was singing to me personally. At the time, this actually made me think I was straight. But now I wonder: did I want him to be my boyfriend or girlfriend? Did I want to be his girlfriend or boyfriend? I didn’t know the answer to either of these questions, but I definitely wanted him.

I’ve spoken to a few friends who always felt they were obsessed with Taylor at the height of Hanson’s popularity. One friend told me that she had been obsessed with him and thought that was “possibly because he was very feminine looking.”

A different friend described the way that she started to dress like Taylor and grew a rat’s tail like his. “This was all just before my bi-awakening, and I do think about the fact he was quite feminine and beautiful… when I think about Tay he’s such an interesting symbol of early explorations and fascinations to do with both sexuality and gender,” she said. “But I also sometimes think about how in admiring Tay, I almost wanted to be him — genderqueering, really. It is something that is quieter but still exists in me now as an adult.”

I met a lot of interesting people during my Hanson-obsessed days. Conveniently, dial-up internet had just come along, so I joined the IRC chat room called “Hanson” and had weird conversations with lots of Hanson-obsessed Australians. I ended up with two short-term internet boyfriends and more crushes, and in the middle of a love triangle with a girl and a boy. At one point, I listened to the Brandy and Monica song, ‘The Boy Is Mine’, on repeat.

Despite being immersed in the drama of the chatroom, I daydreamed about Taylor and his family constantly. Someone from ‘real life’ lied to me and told me she knew the family, and went so far as to construct a fake American phone number for me to call in Tulsa. When I called it, I reached an answering machine message recorded by someone claiming to be Diane, their mother. Things were starting to get messy.

Taylor wasn’t my only androgynous obsession. Baz Luhrmann cast Leonardo DiCaprio and Claire Danes as Romeo and Juliet in his 1996 film adaptation, and for a questioning teen, this film was very helpful; I fell in love with both Leo and Claire by the fish tank scene. But none of this struck me as queer. It couldn’t have; I never came across the word queer back then, other than when my British grandmother used it, forgetting that it was not politically correct.

It was never the fighting scenes or dramatic conflict that stoked the fires of my crush on Romeo. It was when he brooded over Rosaline (a name so similar to my own that it had to be a sign) and then over Juliet. His mopey disposition pleased me, as an angsty teenager. It was exactly what I hoped that teenage boys were like on the inside, even though I had had enough experience to know better.

It wasn’t just Luhrmann who came through with the queer goods in my youth. Wild Things (1998) and Cruel Intentions (1999) were more overt about it. I didn’t love the characters in the films, but I cherished their queer lust. There was Scully on The X-Files, ready to confuse me with the way she looked and behaved in power suits, especially when she took Mulder down. Again, writers and academics have mused on the queer nature of the show at length.

Now I see that I wasn’t ready to come out, so I continued lusting over men who I would now describe as androgynous or queer. During this time, the objects of my affection included Daniel Johns from Silverchair, who wore a T-shirt that said “Nobody knows I’m a lesbian”, just to mess with me, I’m sure. You may notice the physical similarities between him and Taylor Hanson.

Of course, things are different now. I no longer have to go digging for hidden subtext. I keep finding out that writers, actors and directors I used to love are queer. Ann M. Martin, creator of my beloved series, The Babysitter’s Club, which I used to think was the most heterosexual thing I had ever read, has a female partner. Of course, now we all need to re-read all of the books to consider them in this new light.

It has taken a lot of analysis to make sense of my deep and relentless love for Taylor Hanson. I finally understand that my appreciation for Tay may have had different implications than I thought. At the time, I understood things in a basic way. “I am attracted to Taylor,” my brain would say, “therefore I must be straight”. Now I realise that my attraction to men and women can be distinct and separate from whether I am gay, straight, bi, pansexual or other.

Our crushes don’t always have to be determined by genitals or gendered behaviours. Everyone should feel free to form crushes on people who are the same or different gender or sex to you. That’s why I like the terms queer and sexually fluid, as they feels so much more free.

Sometimes, you might react sexually to someone and not fully understand the reasons. I don’t think most of society have fully analysed their own gender identities enough to make sense of their sexual identities. When I came out as bisexual last year, more than a decade after I came out as a lesbian, I felt relief. Bisexuality and pansexuality refer to one’s attractions without making any statement about one’s gender. The terms “gay” and “lesbian”, however, are distinctly gendered.

In my case, I now realise that it doesn’t matter if I was attracted to feminine, masculine or non-stereotypically gendered traits in Taylor Hanson, Leonardo DiCaprio, Daniel Johns, Neve Campbell and Gillian Anderson. I may have swooned over their long hair and pretty faces because it made them seem like women, or seem less like men. I’d like to think, though, that I appreciated their beauty because it was so different and refused to be forced into societal binaries.

–

Roz Bellamy is a Melbourne-based writer, editor and teacher. She has written for Archer Magazine, Daily Life, Everyday Feminism, Going Down Swinging, Seizure and The Vocal, and her writing was shortlisted for the Scribe Nonfiction Prize. Read more of her writing here and connect with her on Twitter.