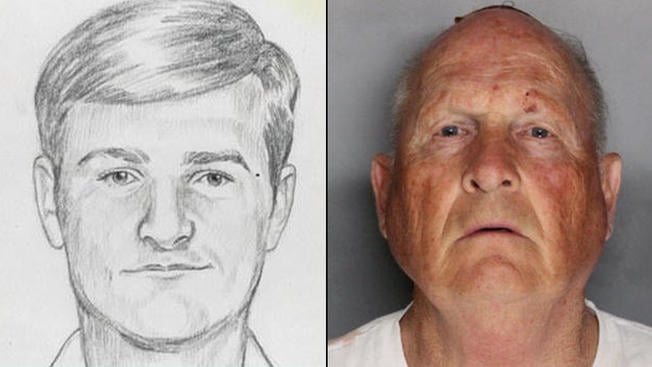

On April 26th 2018, people around the world were very excited — not about a new film trailer, or a celebrity baby, or the renewal of a TV show — but about the arrest of a man suspected of being the infamous Golden State Killer. True crime was the pop-cultural event that everyone was obsessed with.

Between 1974 and 1986, the rapist and murderer known variously as the East Area Rapist, the Visalia Ransacker, the Original Night Stalker and the Golden State Killer, caused terror across the state of California.

Earlier this year, police arrested a 72-year-old man named Joseph James DeAngelo, accused of committing more than 50 rapes and 12 murders. Since then he’s been charged with the murders of four victims.

It’s certainly a dramatic case, and the arrest was global news at the time. But there’s a difference between news and pop culture — terrifying murders, gory crimes and fucked up bullshit like the Golden State Killer have filtered their way into the pop culture sphere.

It’s been that way for a while now, with true crime podcasts, documentaries, films, books and TV shows all huge, mass-appeal forms of entertainment. There’s no need to argue about it, as we’re in the midst of it.

The story of the Golden State Killer was popularised via several mediums — it was a viral article in LA Mag, which turned into a popular book called I’ll Be Gone in The Dark. It was discussed on multiple true crime podcasts, including the ridiculously popular My Favourite Murder.

It’s worth posing — as many have — the uncomfortable question about whether it’s insensitive and weird for people to be obsessed with murder — just because it’s been popularised, doesn’t mean it’s necessarily right. We wouldn’t all be tuning in to a podcast called My Favourite Sexual Assault, for instance.

But while we should be interrogating the motives behind our true crime obsession, we should also be aware of the consequences. Because just maybe, pop culture true crime communities are helping make the world a better place.

Good Consequences

“I think there’s something different happening right now,” said Brad Simpson, the producer of the true crime show The People v. O.J. Simpson. “Great true crime stories aren’t just about a crime, they’re about a rupture in society…I think people are interested in justice right now in a way people haven’t always been.”

Our obsession with murder and crime and the darker side of society isn’t new. The world stops for high profile crimes like the OJ Simpson trial, the Lindbergh baby abduction, the Manson murders and the murder of JonBenét Ramsey. These kind of cases permanently alter society, exposing us to shocking criminal behaviour and to the often ignored or forgotten underside of society. They are jolts to the system, fascinating in their strangeness and darkness.

JonBenét Ramsey

But there’s a difference between high profile cases that get a lot of attention, and this current saturation of true crime.

Now, instead of simply being a pearl-clutching spectacle, people are interested in the causes of the crime, the consequences, the personalities, the nitty-gritty of it all. The reason we’re interested in crime has evolved. We are more than just spectators now — we expect change.

You only need to look at true crime pop cultural events like the first season of Serial, the investigative podcast produced by This American Life. Serial took a basically unknown case — the murder of US high school girl Hae Min Lee in the nineties, and the subsequent trial and jailing of her ex-boyfriend Adnan Sayed — and brought it to an audience of more than 180 million people, by rough tally.

Arguably, the murder itself took a backseat to the question of whether or not Sayed was guilty, as the proposal of the investigation was about his possible false imprisonment, about the shakiness of the case that convicted him, about the intricacies of race and privilege in the American judicial system.

Similarly, the Netflix TV documentary Making a Murderer followed the story of Steven Avery, who served 18 years in prison for the sexual assault and attempted murder of a woman, before being completely exonerated by DNA evidence. However — gasp — he was then arrested years later for the murder of another woman. Again, that show is less about the crimes themselves, and more about the issues of judicial process, police corruption, and justice.

Both these examples show that we’re examining the nature of crime, rather than just being scandalised by it. And that examination is having consequences.

Good consequences.

The Golden State Killer, Or How Crime Nerds Solved A Cold Case

The Golden State Killer wasn’t just an interesting case because of the deep pop-cultural interest in the crime — it was remarkable because that interest led to engagement with the mechanics of the case, and that engagement then helped lead to it being solved.

Crime nerds get shit done.

The Golden State Killer, although he wasn’t known by the name at the time, was big news in California during the period he was actively committing crimes across the state. But after he went silent, he fell off the radar for most people, lingering on as a stubbornly unsolved case for the police, and a horrifying memory for his many victims.

That was, until crime writer Michelle McNamara came along.

McNamara, to put it bluntly, was obsessed with solving the Golden State Killer case. She spent her days and nights poring over autopsy reports and crime scene photographs and 1970s-era police files, chasing the Golden State Killer (whose name she totally coined, btw).

“His capture was too low to detect on any law enforcement agency’s list of priorities,” she wrote. “If this coldest of cases is to be cracked, it may well be due to the work of citizen sleuths like me (and a handful of homicide detectives) who analyse and theorise, hoping to unearth that one clue that turns all the dead ends into a trail.”

McNamara published her findings on the True Crime Diary website and later wrote them down in more detail in the book I’ll Be Gone In The Dark, which was published in early 2018.

She was a committed true crime lover, her fascination and interest spiked by an unsolved murder in her “safe” neighbourhood when she was a child. She turned her passion and talent into a vocation. But she wasn’t a detective or law enforcement officer.

Paul Holes from the Contra Costa Sheriff’s Office, who has worked on the Golden State Killer case for 20 years, regarded McNamara as his investigative partner. Holes credits her with not only recognising new angles, but also being able to bring together people who weren’t able to be in contact with one another.

“She had the freedom to call anyone she wanted — victims, witnesses, original investigators across various jurisdictions. Michelle talked to people that I hadn’t and found out details that weren’t written in the case files, and she would pass those on to me.”

She was single-minded and obsessive about tracking him down, but tragically she died both before her book was published, or the GSK was captured.

After she died, McNamara’s husband, the comedian and actor Patton Oswalt, decided to make sure her book would be finished and published. He recruited the help of the crime journalist Billy Jensen, and a researcher, Paul Haynes, for the job.

“In writing the book, she began to recruit retired homicide detectives and cops from all these different jurisdictions and precincts and cities. And she got them to pool information,” Oswalt said last year during an interview on NPR’s Fresh Air. “But her research was so meticulous and so complete that they would contact each other and say, talk to Michelle. She knows. This person is actually not some weird, overenthusiastic amateur. She wants to put the bracelets on this guy.”

The information that McNamara pulled together is credited with unearthing new leads for the detectives. Furthermore, the immense buzz that her posthumous book received — a bestseller, chart topping title, endorsed by Gillian Flynn and other famous writers — brought the Golden State Killer case a new wave of attention.

The Golden State Killer suspect Joe DeAngelo was just officially charged with the murders of Offerman, Manning, Domingo and Sanchez. #justice #rememberthevictims pic.twitter.com/qbspxv0VAI

— Billy Jensen (@Billyjensen) May 10, 2018

Talking to Junkee, Jensen gives Michelle McNamara a lot of the credit for the eventual capture of the GSK.

“The case was not terribly well known until Michelle wrote the article in LA Magazine. That led to the book deal. She had already renamed him, but he was still flying below the radar of many of the people in power — the types of people that authorise more money and resources for investigations,” he said.

“Her death was an international story. And it was about a woman who was trying to find this serial rapist and murderer. Two months later, they have a press conference and announce a reward and more resources. All the focus came from that. It was her life’s work that formed the foundation, but it was tragically her death that put the spotlight on him and the pressure on the people in power to make something happen.”

But many of the law enforcement officers who made the arrest have been carefully downplaying the input of McNamara and the true crime community.

“That’s a question we’ve gotten from all over the world in the last 24 hours, and the answer is no,” Sacramento County Sheriff Scott Jones told reporters, regarding the role of McNamara’s book in helping identify and capture the Golden State Killer.

They did, however, acknowledge that her work built public interest in the case, which can have the effect of lending an old investigation more urgency and, potentially, more resources.

“It kept interest and tips coming in,” Jones said, but “other than that, there was no information extracted from that book that directly led to the apprehension.”

Trace

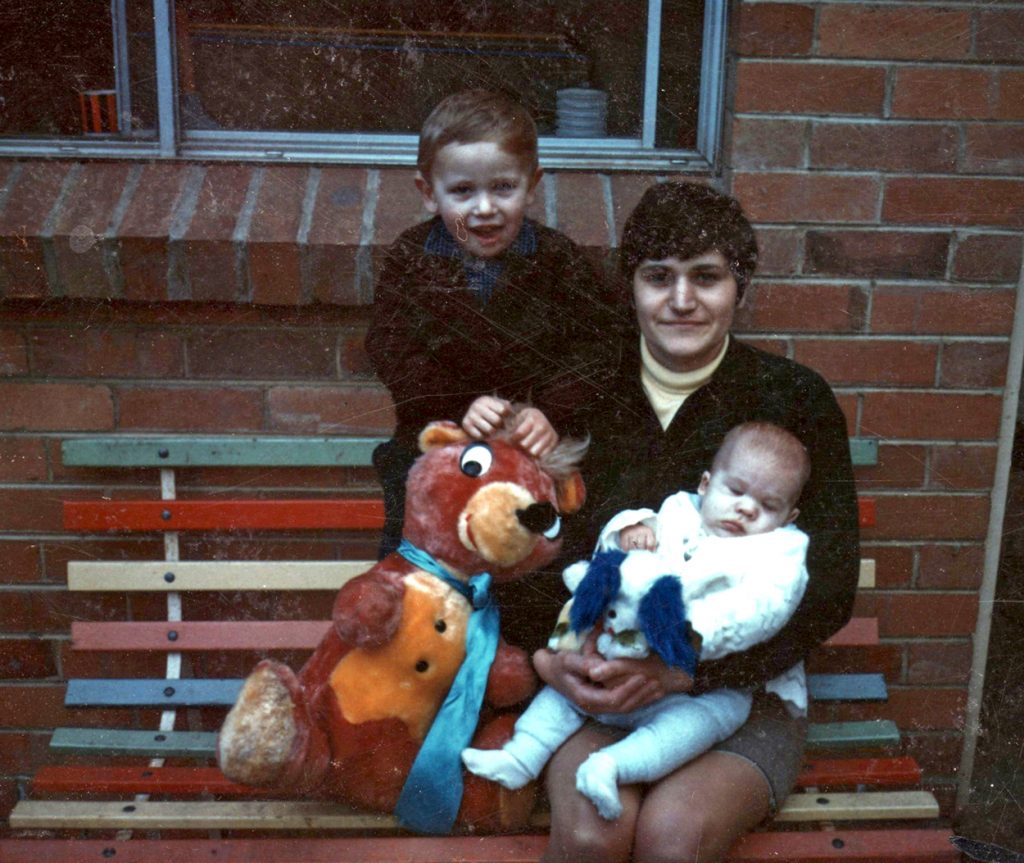

Maria James and her sons Mark and Adam. Photo courtesy of Trace podcast.

Regardless of what the cops are saying, there’s a clear trend of true crime fans and journalists making a real impact on crime investigations.

We keep seeing examples of pop culture investigations into crimes grabbing the public’s attention and influencing the actions of courts and law enforcement. We have Michelle McNamara’s amazing pursuit of the Golden State Killer. Without Serial becoming the biggest true crime podcast ever, an appeals court might never have ruled that Adnan Syed should be granted a new trial.

An excellent example of an Australian version of this phenomenon is the amazing ABC podcast, Trace, a deep dive into the 38-year-old cold case murder of Melbourne bookshop owner Maria James.

Talking to Junkee, Trace creator and investigator Rachael Brown says that she began the investigation with the intent of making a positive change to a cold case. She was drawn to the possibility of finding new leads, of shedding new light on a tragic murder.

“I definitely wanted developments,” she said. “I know a lot of true crime pods are more in the storytelling vein than the investigative realm, but the reason I did this was for new leads and information. I didn’t see any point in a rehash of what we already knew. I wouldn’t want to put the family through that.”

Maria James was stabbed to death in the back of her second-hand bookshop in Thornbury, Melbourne in 1980. Throughout the course of Trace’s investigation, we discover that she was murdered on the same day that she intended to confront a paedophile priest, Father Anthony Bongiorno, over the alleged sexual abuse of her youngest son.

Last July, the podcast revealed this priest was wrongly ruled out as a murder suspect because of a DNA bungle.

Brown was drawn to the Maria James case after a colleague told her about an intriguing detail — that an electrician came forward and gave the police a statement about seeing a priest covered in blood on the day of James’ murder — a statement which had never seen the light of day. It’s a pretty juicy starting point for any podcast.

While investigating James’ murder, Brown utilised the fans of the podcast as a crime-solving tool, using the vast networks opened up by the success of Trace to track down new clues and leads.

“I had a very elaborate publicity plan — not to get publicity for the podcast as such, but to reach that final person holding the missing puzzle piece. So, I think the internal tie-ins, the external support, I think that helped a lot getting new leads hard and fast. And I also think listeners maybe liked being participants and not just consumers, that they could have a personal role in helping this family.

“I think that’s one of the podcast’s biggest achievements, is that it shows that everyone can change the world in their own little way.”

From this, Brown managed to find a much desired witness who saw a man running across the street of the bookstore after the murder, as well as several other hugely important clues, such as an item with potentially damaging familial DNA on it.

“This podcast exceeded even my lofty expectations for it,” says Brown. “We’ll soon hear if the coroner will decide whether to reopen the inquest on the basis of eight new facts and circumstances that Trace has unearthed. It’s illuminated some massive failings within the church, and the Victorian police force.”

A Sensitive Subject

But Brown feels uncomfortable with the idea of Trace being classified as entertainment, no matter how, well, entertaining it is. She believes that a lot of podcasts treat crime like a spectator sport, and that she’d “feel quite ill if Trace ever fell into that bracket”.

But Brown feels uncomfortable with the idea of Trace being classified as entertainment, no matter how, well, entertaining it is. She believes that a lot of podcasts treat crime like a spectator sport, and that she’d “feel quite ill if Trace ever fell into that bracket”.

“This was a huge concern for me,” said Brown. “I wanted Trace to be both forensic and compassionate. And I thought that that was possible. But my early caveat was getting the blessing of [Maria’s sons] the James’ brothers and [Detective] Ron Iddles, and had they said no then I wouldn’t have done it.”

The reality of the crime hits home in Trace when you listen to the multiple interviews with James’ now-adult sons, Mark and Adam, who have spent the majority of their lives with their mother’s unsolved murder hanging over them. It can be hard listening at times, but there’s no doubt they’re grateful for Brown’s attention and the concern of the public in their mum’s murder.

“I always had that in the back of my mind — why I was doing this,” said Brown. “It wasn’t for people’s entertainment, it was to try to help solve a murder. And it was getting answers for the James boys. So that was in everything.”

“The nicest thing that Mark said to me is that he doesn’t feel so alone anymore, because he’s had lots of people come up to him, like in shopping centres and say, ‘good on you, keep going. We’re all behind you’. So that’s a lovely thing to hear.”

One of the biggest criticisms that true-crime lovers receive is the catch-all cry of “ghoulishness”. This can be anything from people’s ickiness with discussing decapitated bodies and melted torsos at the dinner table, to accusations of pop-culture diminishing the humanity of victims.

“My most significant qualm about the true crime zeal is that it lacks empathy for the victims, and that, all too often, it’s content to regard merely portraying horrific acts of violence as a meditation on why, exactly, that violence occurs,” says Laura Bogart, in an article explaining why she believes pop-culture’s true crime obsession is bad for society.

It’s a good point — true crime in pop culture does make entertainment out of someone’s worst, most traumatic moment. But, more and more people are getting drawn into that world.

Girls Just Want To Have Fun (And Not Get Murdered By Men)

Aimee Knight has thought a lot about what attracts true crime devotees to the genre.

“It’s pretty ‘normal’, for lack of a better term, to want to peek at something that could harm us,” says Knight, about the forbidden lure of pop-crime. “It helps us evaluate risk and danger — or so my psychologist assures me.”

Aimee Knight is well placed to discuss issue, given she is currently working on a book exploring the connection between Australian women and the true crime boom. She emphasises that women are linked to rise of true crime popularity — the fans bonding over their shared interest in true crime are almost overwhelmingly female.

“In my experience, true crime fans generally identify as women. That’s curious to me because, historically, true crime and crime fiction authors have mostly been men, although that’s shifted in the last decade or so.”

Knight points me towards an American study of true crime readership which establishes that women are more drawn to books featuring real life violence, crime and murder — funny, given men are far more likely to commit that violence, crime and murder. But it could be precisely that reason why women are drawn to these communities — because overwhelmingly, they have the most to fear from violent criminals.

“There’s a lot of speculation about why women are fascinated by true crime, particularly when so much of this ‘content’ centres women as ‘victims’ (occasionally, survivors),” muses Knight, when I ask her why she thinks true crime communities are dominated by women.

“Are we socialised to be more empathetic, understanding and tolerant? Does storytelling offer structure, order and catharsis in an unpredictable world? Perhaps we’re desensitising ourselves to real and present danger — prepping for it, even.”

It’s this phrase “prepping for it” that intrigues me. Are communities of women drawn to consuming true pop culture content because they’re actively in fear of being murdered? At least in part, it seems they are.

Probably the most popular and energetic pop-crime community is that of the podcast My Favourite Murder, which currently boasts more than 216,000 members on its Facebook group alone. The beloved hosts of the podcast are emblematic of the community — both delighted and revolted by murder.

Comedians Karen Kilgariff and Georgia Hardstark spend each episode talking about a murder that interests, enthrals and often horrifies them. They are famous for their digressions, their chatty, irreverent and sometimes extremely real musings on almost everything. It’s a weird balance to strike — laughing and crying about someone’s horrible death.

But they generally pull it off, and one of the ways they do that is by centring the conversation around empathy for the victims. MFM is always on the side of women and victims.

As a consequence, Murderinos (which is what the community of fans call themselves) have adopted a lot of the regular refrains from the show as slogans. “Fuck politeness”, which tells women they shouldn’t put themselves in unsafe situations just to be polite, is probably the most popular of the sayings. Don’t take that lift that a dodgy guy is offering because it’s awkward to say no, don’t worry about calling the police about something suspicious, don’t hesitate to ask to be walked home at night.

It’s followed by several others — “call your dad, you’re in a cult,” “don’t go into the forest,” and the show’s own catchphrase “stay sexy, don’t get murdered.” They’re all cute, bite-sized ways of women banding together as a community and sharing support and advice and, above all, solidarity. These communities are important for women surviving in a world of violent men.

Aimee Knight agrees. “Based on a sample of my four closest murderinos, true crime fandom is accelerating in step with public conversations about mental health, women’s rights, sex worker safety, intimate partner/family violence, bystander intervention and loads more real-world issues,” she says.

It’s unlikely that a community of podcast lovers is going to change the course of a case in the same way that an investigative journalist might, but these groups do have a function: they’re driving the conversation around women’s safety, creating support for women as a community. They’re important.

Thank You, Murder!

Ideally, people wouldn’t get murdered anymore. That would be nice. But in the meantime, we’re going to have to keep skirting the awkward boundary of deploring the act, while still being entertained by stories and depictions of interesting true crime in popular culture.

That difficult line isn’t going to go away — in fact, it’s much more likely that as our true crime saturation continues, we’ll make more and more mistakes, such as the controversy surrounding privacy and suicide that occurred around Serial’s most recent podcast, S-Town. Even while writing this article, one of our interviewees landed in hot water after releasing traumatic information about a murder to an unsuspecting, grieving mother in his new book.

But that doesn’t mean we shouldn’t celebrate that our big pop culture love of true crime is leading to real and good changes in our society — and will very probably continue to do good work. New developments in investigations like Trace are unrolling as we speak, and we can follow along by liking, rating and subscribing.

And there’s new always going to be new and exciting work — we only need to look at journalist Allan Clarke’s new podcast Blood On The Tracks, a five year investigation into the suspicious death of 17-year-old Indigenous man Mark Haines, whose body was found on the railway line outside Tamworth in January 1988, in what is sure to be a sensitive and important topic for modern day Australia.

Hooray for crime solving that also leads to cool shows!

Let’s just hope it doesn’t also encourage the murderers.

—

Patrick Lenton is an author and staff writer at Junkee. He tweets @patricklenton. He does not endorse murder.