In 1891, Melbourne’s sewers caught fire, the city flooded, a pair of legs turned up in the street, and a plague of locusts arrived. In the midst of all this, a precious medieval weapon was stolen from Victorian Parliament, sparking one of the greatest unsolved mysteries in Australian history.

What with all the bickering and politics that goes on in Parliament, it’s easy to forget that our system of government centres on a gold-plated medieval weapon meant for violent bludgeoning.

This weapon is better known as the ceremonial mace. Keeping one around is a tradition that Australian parliaments inherited from Great Britain, and it’s mostly pretty boring: at the start of each sitting day in parliament, the mace is carried in by the Sergeant-at-Arms; at the end it is carried out, and the rest of the time it sits on a table. Occasionally a politician feeling particularly fired up about something will seize the mace threateningly, but that’s about as dramatic as it gets.

Unless we’re talking about the Parliament of Victoria, that is. 127 years ago, its mace went missing, never to be seen again. The story of its disappearance involves 19th century Melbourne’s most powerful people, an infamous brothel, the bottom of a river, a former Premier, and a disembodied pair of legs. This is that story.

’Twas The Night After Parliament, And All Through The House…

’Twas The Night After Parliament, And All Through The House…

Our story begins just after midnight on Friday October 9, 1891. Parliament had just wrapped up, and two men were attending to the final task of the day: locking the ceremonial mace away in its box for safekeeping until the morning.

Those men were Frederick Davis, the Speaker’s messenger, and George Edward Upward, the sergeant-at-arms and bearer of only the second most stupid name in this story. The mace in question was a truly dramatic stick: 1.5 metres long, made of solid silver with gold plating, weighing at least 7.5kg, and twined with gold roses, thistles, shamrocks and eucalyptus.

In a small room in Melbourne’s parliament, Upward and Davis presided over what was either a mistake or a stroke of criminal genius. At twenty minutes to one they locked the mace in its box. At 1pm the next day, the box was still locked, but the mace was gone.

Less-Than-Proper Parliamentary Proceedings

The Speaker only told Parliament the Mace was missing the next Tuesday, after it had been gone for four days. A day later, a description of the mace was sent to every police station in the state. An older, slightly shabbier mace made merely of gold-painted wood was dusted off, and the whole event was largely swept under the rug — police investigated, sure, but the investigation turned up very little in terms of concrete leads.

And then, nearly a year later, the brothel rumours began.

They first cropped up in either the Sydney Bulletin or Table Talk, a popular weekly gossip rag, and spread from there to the most respected newspapers in the state.

The story, as the newspapers had it, was this: an unnamed group of parliamentarians, apparently including government ministers, held a party on the night of the mace’s disappearance. A number of sex workers were in attendance — in the late 1800s, Victorian Parliament was literally across the road from Melbourne’s booming red light district.

Was it actually taken to a brothel? We don’t know. Did someone fuck the mace? Possibly.

According to the papers, the merry party removed the mace from its cabinet, and headed to a brothel with it. There, it was used in what have been variously described as “low travesties of parliamentary procedure”, “less-than-proper parliamentary proceedings”, and “fearful orgies”.

Was it actually taken to a brothel? We don’t know. Did someone fuck the mace? Possibly. But the rumours captured the imagination of the public at the time, and worried Parliament enough that its members furiously debated how to respond to the allegations for three hours straight, one night in January 1893.

After all, an article in the Ballarat Courier argued that if the rumours were true, “Parliament should be shut up altogether lest its evil example debauch the country”, and we all know nothing frightens politicians more than the prospect of losing their power.

“A False and Ridiculous Position”

To say Parliament was panicked by the rumours is an understatement. The turn of the century in Melbourne was a precarious time, and men were already unsettled by what historian Kathryn Ferguson describes as women “gadding about town on bicycles demanding the vote”.

If women on bicycles made them uncomfortable, you can imagine how they felt about women performing what were then considered highly degrading sex acts in front of, or perhaps even on, the ultimate symbol of parliamentary authority.

The night the House debated the rumours, the room was fiercely divided: half of the MPs thought the rumours were so deeply degrading that the Government must respond at once; the other half thought the rumours were so profoundly degrading that the Government mustn’t stoop to their level. Most of the parliamentarians vehemently refused to even consider the fact that the rumours might be true.

One bloke said it wasn’t necessary for him to deny any of the rumours “because everyone knew there was not one tittle of truth in them”.

The Premier, William Shiels, described the article as “a tissue of grossest lies”, and members lined up behind him to make it clear that they couldn’t possibly imagine a government minister fucking — let alone fucking a mace. One bloke said it wasn’t necessary for him to deny any of the rumours “because everyone knew there was not one tittle of truth in them”.

Eventually, someone moved a motion to call the publisher of the Ballarat Courier, the more reputable newspaper in question, to Parliament to explain himself. A few days later, a doddery old man named Robert Clark wandered into the chamber, hand to his ear as a makeshift ear trumpet so he could hear what all this fuss was about.

Once he got the gist of it, Clark swiftly denied having even read the article published in his own newspaper, and issued a full retraction and apology. Parliament declared him suitably admonished, and everyone went on their merry way.

Finally, Someone Thinks To Investigate

At least, everyone tried to go on their merry way. As it turned out, devoting three hours of Parliament’s time to bickering about the missing mace piqued the public’s interest as to where the mace actually was, if not a brothel.

So it was that in February 1893, a year and a half after the mace was stolen, a Parliamentary inquiry into its whereabouts was finally launched. That inquiry largely rehashed the evidence gathered by the police over a year earlier, but it was the first time the public had heard it. It was a game changer, because it introduced the people to a witness named James Merrick.

Merrick was a tram driver, and he had been driving past the back gate of Parliament right around the time the mace was believed to have been stolen. And as he was passing, he told the inquiry, he saw a man come running out of the gate.

“He did not hail me,” Merrick reflected, “but ran across and jumped on to the dummy [of the tram]. A parcel which he carried swung around and struck the stanchion. He nearly fell off and I stopped, but he recovered himself and I went on.”

Merrick then ponderously described the parcel the man carried as he sprinted out of the back gate of Parliament and leapt onto a moving tram. “The parcel was wrapped in brown paper and was about 5ft long,” he said, noting that when the man stood on the tram with it, it came up to about his shoulder.

“It was tied up roughly, and when he was on the dummy he stood it with the big end down,” he continued. “At the top of the parcel there was a piece of brown paper put over like a hood and bound round. I did not see the contents, but it struck the back post of the dummy and rang. It was not wood, but metal.”

You know what else is around five feet long, made of metal, with one end much bigger than the other? Oh, just the parliamentary mace. The one that, by this stage, had been quite prominently missing for almost two years. Quintessentially Melbourne, too, that the getaway car was in fact a tram.

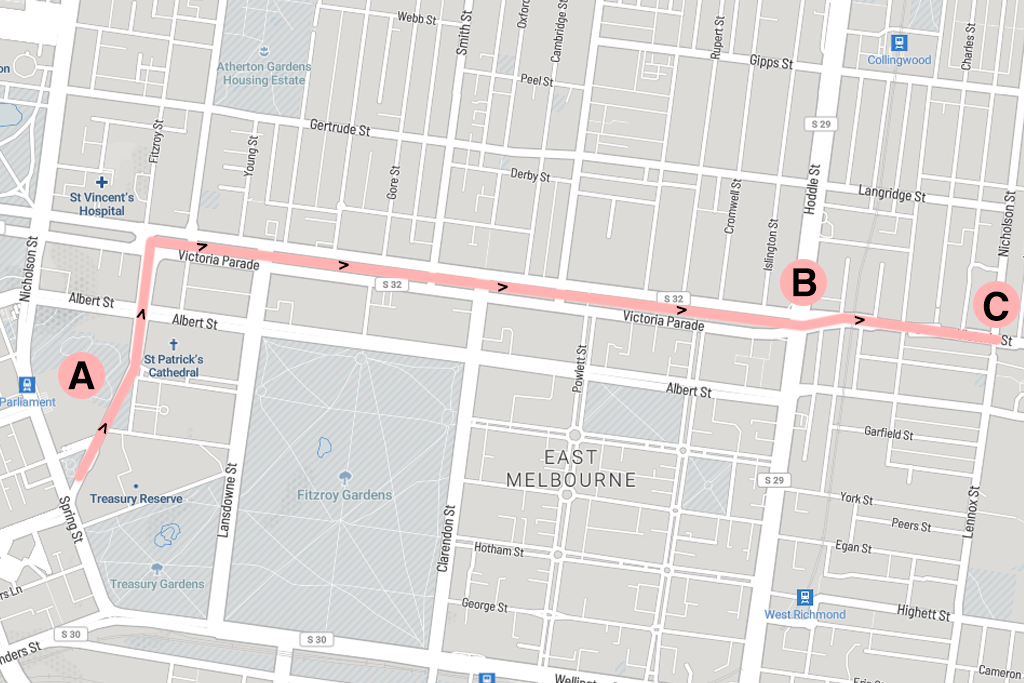

A map of the tram journey taken. A is the Parliament, B and C are the two points the thief may have alighted at. Map styling thanks to Le Shine theme on Mapbox.

Merrick went on to identify the two stops the man may have alighted at, and then just went ahead and named him: it was Thomas Jeffery, the electrical engineer at Parliament.

“The reason I noticed him was that he nearly met with an accident and I had to pull up to prevent it,” Merrick summed up. “He was not looking where he was going when he got off and nearly ran against a lamp post.”

“I also noticed the peculiarity of the parcel.”

Thomas Jeffery, when questioned about all this, was less than helpful, even suspicious. When police first questioned him, he couldn’t remember taking a parcel home at all on the day of the theft, let alone a distinctly mace-shaped one. The police searched his house anyway, but came up empty handed.

And then, under pressure, Jeffery’s story changed. Actually, he said, he did sometimes take parcels of firewood or other odds and ends home; it was conceivable that he had indeed been sprinting away with one on the day in question.

But despite being asked repeatedly to show police this parcel, Jeffrey stalled. When he did finally bring one in, Merrick said it looked nothing like the one on the tram. Jeffery maintained his innocence, but he couldn’t prove it. The police had strong suspicions, but they couldn’t prove them either.

What Do Dismembered Legs Have To Do With This?

Unfortunately, the mystery of the missing mace alone was not enough for Melbourne. In 1892, as investigations into Jeffery stalled and the brothel rumours took off, something else was thrown into the works: two dismembered legs, and shortly after a pair of dismembered arms also.

The legs were found in an abandoned parcel, left in a street in Hawthorn. The arms were found a week later, wrapped in newspaper and dumped several kilometres away in Fawkner Park. They were going green and white, beginning to decompose.

“There may or may not have been a murder, but it is indisputable that the head and body of a human being are missing.”

With these four limbs and some hefty deductive reasoning, the public was able to boldly surmise that, as newspaper column The Peerybingle Papers put it at the time, “there may or may not have been a murder, but it is indisputable that the head and body of a human being are missing.”

You may at this point be wondering what this has to do with the theft of the mace. As the paper put it, “the facts that the most conspicuous and public valuable in the colony can disappear, and that legs and arms can sensationally and mysteriously appear without leaving trace whence they come or whither they have gone, does not tend to make the public feel comfortable, nor do they inspire confidence in the skill of our detective department”.

And while that link is more underwhelming than, say, the mace being used to furiously dismember the legs (which would admittedly be difficult given that a mace is a blunt weapon better suited to bludgeoning), Peerybingle has a point: the thing a missing mace and a dismembered pair of legs apparently have in common is an incompetent — or corrupt — police force.

So what were the cops doing this entire time? They had actually been investigating quite thoroughly, though the public had no way of knowing this given that their reports were kept confidential, tabled in Parliament for members’ eyes only. Detectives Nixon and Ward — the latter of whom had worked previously on the hunt for Ned Kelly — had spoken to Merrick and Jeffery, searched Jeffery’s house and the brothels, and followed a handful of other leads to dead ends.

By 1893, the detectives were at the end of their tether. They penned an exasperated report admitting defeat: baseless rumours were now so enmeshed in the public imagination, they thought, that “everybody seems to know how it went and where it went with the single exception of the police”.

A Red Light, A River, And One Big Reward

In 1988, the mace made headlines again when archaeologists began work in Melbourne’s old red light district. Newspapers reported that the dig hoped to unearth the mace or evidence of it, and shortly afterwards the leader of the Victorian Liberals, Alan Brown, called for the government to offer an amnesty on the off chance that anyone still had the mace.

Over the decades, the story continued to crop up periodically in newspapers, documentaries, even plays. Each retelling emphasised different details, and the story warped and expanded over time. Leads went cold, witnesses died off, facts were conflated and went bad. For a while, the leading theory was that former premier Thomas Bent took it — a theory that largely grew from rumours and Bent’s maverick style, but not from any discernible facts.

And then, in 2013, a historian named Raymond Wright published a document held by Thomas Jeffery’s descendents. Written by Jeffery’s son Henry William Jeffery in 1963, it claimed to tell the real story, as told to him by his father.

If that story is to be believed, Thomas Jeffery was arrested by the police one day early in the investigation, though not for the theft of the mace. The story behind that arrest is complex, involving an altercation with a cop, and Jeffery assaulting an MP.

The details of the arrest aren’t important: what’s important is that no paper record of it exists

The details of the arrest aren’t important, though: what’s important is that no paper record of it exists. According to Henry, that’s because Jeffery had the charge against him withdrawn by threatening to reveal what had actually happened to the mace.

According to Jeffery, a group of MPs had a habit of staying overnight in Parliament after the house rose, often to party. Jeffery knew about this, because as the house engineer he also often stayed the night.

Jeffery’s son wrote that on the night the mace disappeared, those MPs stayed late, and kicked on to a brothel with the mace. In the morning, they panicked when they couldn’t smuggle it back to Parliament, and instead paid off “two city crooks” to dump it. The crooks supposedly dumped the mace in the Maribyrnong river, just upstream from the Colonial Sugar Refinery.

A marks the Colonial Sugar Refinery on the Maribyrnong River, where the mace was reportedly dumped. B marks Parliament, where the mace began its journey. Image created with Mapbox.

This story regrettably can’t be proven, and it requires several grains of salt. Henry William Jeffery was eight at the time of the mace’s disappearance, and heard the entire story second hand from his father. Thomas Jeffery, meanwhile, heard several parts of the story second or even third hand — the details about the mace’s ultimate resting place came to him several years after the original scandal, via a friend of his who heard from a priest who’d spoken to the two city crooks in prison.

Still, we can entertain for a moment the possibility that the story is true. That the mace was taken to a brothel, then flung into a river in the harsh light of the morning after. That maybe it’s still there, covered in silt and algae and whatever else grows in rivers, attended to by a small submarine parliament of yabbies or the like. A fitting end for a fancy stick, though probably not a good omen for parliamentary authority in the state of Victoria.

Then again, maybe the mace isn’t in a river. Maybe it’s in a backyard, or a brothel, or melted down, or stashed somewhere in the depths of Parliament itself. To this day, the Parliament of Victoria offers a $50,000 reward for information leading to the return of the mace.

If you’ve got a better theory, get in touch.

_

Sam Langford is one of Junkee’s Staff Writers. You can pass on hot tips about missing medieval weapons on Twitter at @_slangers.