When one half of Amyl & the Sniffers log on to a Zoom meeting with Junkee, the reality of their new album Comfort to Me has not yet set in.

It hasn’t yet shot to number two on the ARIA album charts, outselling teen megastar Olivia Rodrigo and only being kept off the top perch by the Drake juggernaut Certified Lover Boy. It hasn’t yet received glowing reviews from roughly every publication on the planet, scoring a rating of ‘Universal Acclaim’ from Metacritic. It hasn’t yet cemented itself as one of the biggest Australian albums of the year, from a band widely regarded as the country’s premier punk band. In fact, it’s not even out yet at all.

Right now, the band’s singer Amy Taylor and guitarist Dec Martens are only just becoming acquainted with the reality of Comfort to Me. They’re goofing off in the lead-up, discussing the finer points of the supermarket’s many milk options. “I had a skinny latte this morning, but I somehow felt like it should have been… skinnier?” muses Martens, who’s on the mobile app of Zoom and lounging on his couch. “I’m on that lactose-free milk right now, hey,” says Taylor. “I got too many tummy aches from the normal stuff!”

The banter is flowing — one thing Amyl and the Sniffers have thankfully not lost in the wake of the pandemic. Given it’s not officially out in the world just yet, however, Comfort to Me isn’t quite real yet. Don’t let the cheeky laughs and the dairy discussions fool you, though. Comfort to Me is real — and, at times, very real.

Guided By Angels

Before discussing the points of difference between Comfort to Me and Amyl’s self-titled debut from 2019, let’s hone in on the similarities. The line-up remains intact, for one — after some early changes, the band has centred primarily on Taylor, Martens, bassist Gus Romer and drummer Bryce Wilson. You won’t find any radical shifts into jazz or electronica this time around, either — fundamentally, the band are still loud and rambunctious, as lead single ‘Guided by Angels’ testifies. Quite literally, too: “I’ve got plenty of energy!” boasts Taylor in the verses, before bowling over into the chorus with an idiosyncratic “FARK!” moments later.

While their debut was concocted across the pond in the UK, however, Comfort to Me saw the band working much closer to home — and the reasoning isn’t as initially obvious as you might think, given the circumstances.

“It was so important to us to record locally,” Martens explains. “When we recorded the first album in Sheffield, it was at the tail-end of a three-month tour. We were not only exhausted, but we were really pressed for time — that knowledge of having return flights was really looming over us. It wasn’t necessarily bad, but we obviously felt like it was something that we could improve upon by recording in Melbourne. Funnily enough, we really got more than we bargained for having now spent the last 18 months here. Still, we had heaps more time and we were a lot more relaxed this time around.”

The band brought in producer Dan Luscombe to oversee the creation of the album. A former guitarist for the Drones, as well as a lead guitarist for Paul Kelly, Courtney Barnett and Marlon Williams, Luscombe is a staple of Melbourne’s music community. After going for coffee together, Amyl enlisted Luscombe to record some of the album’s early demos — from which point both parties became certain of the arrangement’s permanent fixture.

“He didn’t stick his nose in too much — which I liked, because I’m pretty stubborn and so is Gus,” says Taylor. “At the same time, he’d chuck in when he felt it was necessary and I reckon it definitely helped. He was like…” Taylor trails off, seemingly trying to grasp her phrasing from thin air. “Y’know those things in bowling alleys that stop your ball from going into the gutter?” The bumpers? “That’s them!” Taylor laughs. He was like that. It was nice!”

“Ninety percent or more of the time, I’m surrounded entirely by males – from greenrooms, to recording studios, to meetings.

Martens enjoyed the experience with Luscombe too, albeit on different grounds. “It’s always nice when the producer is a guitarist as well,” he says. “When we were tracking the guitars, I liked how practical he was. Instead of getting me to think about what I wanted to do, he’d make me go in there and actually do it with whatever we had on us. It limited our options, but when you spend more time playing the part than thinking about it you get results.”

Taylor is also quick to point out the contributions of Bonnie Knight, the album’s engineer who tracked the band at Soundpark Studios in Northcote. “She’s good value,” says Taylor of the sound engineer.

“Ninety percent or more of the time, I’m surrounded entirely by males — from greenrooms, to recording studios, to meetings. Having someone that wasn’t male was really dope — especially knowing she’d be tracking the songs that had this kind of content. Knowing it wasn’t just falling onto one gender of ears, and that she’d have at least some level of understanding as to what I was singing about… it was just great having her there. She’s quite talented, and she worked really hard through the whole process.”

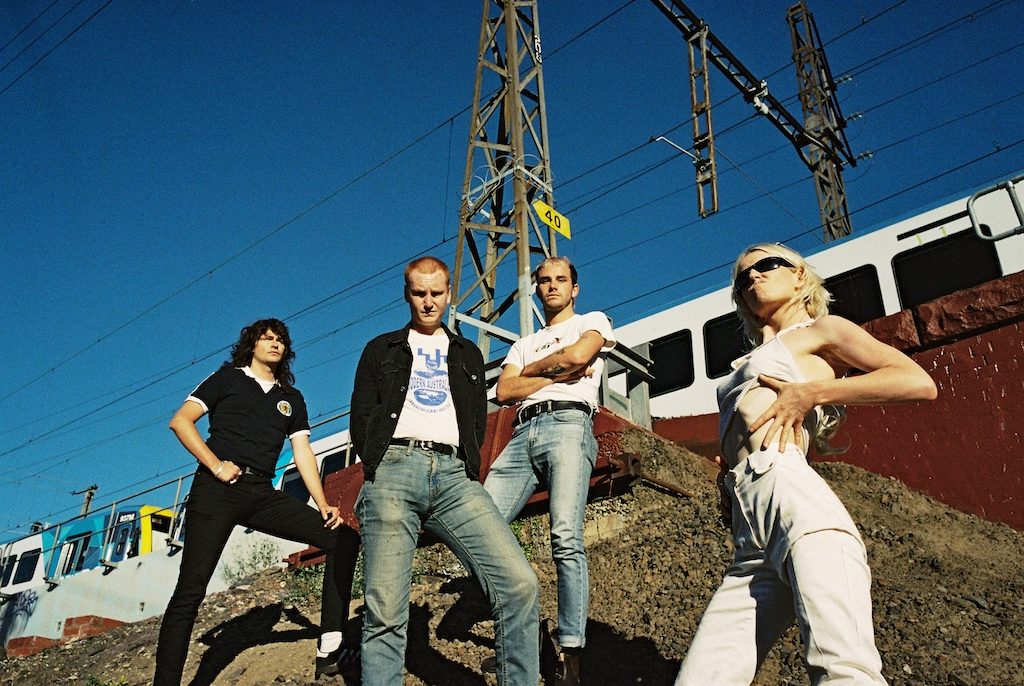

Photo Credit: Jamie Wdziekonski

Don’t Fence Me In

When queried on what she wished to get out of Comfort to Me, Taylor doesn’t hold back. To her, the creation of this record was a matter of survival; less focused on the band potentially repeating itself and more on simply coming out the other side with something to show for it. After all, Amyl had essentially not stopped for nearly four years up to this juncture — what if they came to the end of this whirlwind experience and had nothing to say?

“As long as we could squeeze out any kind of second album, we would’ve been happy,” she says. “That would’ve been good enough. We had to make sure no kind of preconceived notions about us factored in — we always do, but it was especially important now. We knew people would nitpick about the record no matter what we came up with. This was too different, this was too samey, this was too political, this was too jokey…like, you can never win, can you? We’re really proud of this album for what it is.”

“This was too different, this was too samey, this was too political, this was too jokey…like, you can never win, can you? We’re really proud of this album for what it is.”

So, what is this album, exactly? It’s a loud, robust punk record, certainly, but that’s not the full story. It’s a record with more complexity and multitudes than perhaps some were willing to give them credit for. Their tongue-in-cheek humour is still prevalent in songs like ‘Security’, in which Taylor sweet-talks a bouncer: “Let me in yah heart!” she yells, “Let me in yah PUB!” There’s also the note-perfect, one-size-fits-all fuck-you that is ‘Don’t Need a Cunt (Like You to Love Me)’, which sports both one of the year’s best titles and hooks.

By means of contrast, however, there are moments on Comfort to Me that are decidedly no laughing matter. On ‘Capital’, Taylor rages against the government and its utter failure and inaction on…well, just about every front possible, all while the band thrashes and rages on alongside her. “Of course I have disdain for this place/What are you thinking?”, she questions in its final verse. “You took their kids and you locked them up/Up in a prison.”

Elsewhere, ‘Knifey’ is simultaneously one of the quietest and most loudly resonant songs the band have ever recorded. Amidst a steady beat and tense guitars, Taylor details the paranoia and fear that comes from simply walking alone at night. “Please, stop fucking me up,” she pleads to her potential assailant — speaking not as a rockstar, not as a frontwoman, but as a human being with every right to be safe when travelling on their own.

Was Taylor hesitant to address these issues within Amyl’s music? Certainly, but there’s nothing punk rock about reticence. “It felt right,” she says. “These are things that I think about, and all I want to do in my music is express things that I’m thinking about. Those feelings definitely came up when I was writing ‘Capital’, because I felt ill-equipped talking about politics in general. You’re always made to feel like it should be reserved for people in like academia and all that shit. But if speaking about it is only reserved for those people, then it leaves so many people out — and it affects everyone!”

Even with such gatekeeping, Taylor found a way to properly convey her convictions. It’s not nuanced prose, but it doesn’t need to be. It’s better than that: It’s real. “I don’t claim to know a great deal,” says Taylor. “All I know is what I feel and what I see, and I write about it. It’s no different on this song than any other in that regard. Last year, I felt really existential and cynical, so this is just what came out at the end of that.”

When Taylor brought the lyrics of ‘Knifey’ to her bandmates, Martens recalls the room coming to a standstill — particularly when the song itself was finished, and the band were listening back to the mixes with Luscombe and Knight in the studio. “It hit the boys real hard,” he says. “We were just blown away. At the same time, I remember feeling this real sense of pride — it’s such an important message for the whole community, and I was proud that I was able to be a vessel for what Amy was saying.”

Taylor, Martens and the rest of Amyl are aware that a song along cannot cause an entire societal upheaval and solve a larger systemic problem. However, if their peers like Camp Cope and Courtney Barnett can address the issue on songs like ‘Jet Fuel Can’t Melt Steel Beams’ and ‘Nameless, Faceless’ respectively, then Amyl deserve a place at the table too. The more acts placing importance on these all-too-real experiences, the better. “I don’t expect things to change — even when they do, change is slow,” says Taylor.

“I just want to be heard. I have so many experiences of reacting with violence in violent situations, and then being accused of being the insane one. I don’t want to be violent. I don’t want to be intense. I want to be soft, chill and nice. But I have to be extra intense — because the world is extra intense to me.”

Photo Credit: Jamie Wdziekonski

Not Looking For Trouble, Looking For Love

Despite only being in the public eye for a relatively short period of time, a lot of attention has come Amyl’s way. They’ve made in-roads in the UK, thanks to bands like Sleaford Mods backing them up, and their live shows have become a thing of legend for their ferocity and free-wheeling nature. Taylor’s taking all of it in her stride, of course. She cracks herself up when she calls herself a “famous cunt” on Comfort to Me’s closer, ‘Snakes’. This comes right after ‘Laughing’, too, in which she promises “I am still a good girl/When I’m on the telly.”

Martens, for the record, doesn’t mind the attention largely being shifted towards Taylor — her personal Instagram account, for example, averages around 60,000 followers, while the rest of the band’s personal accounts hover somewhere in the 5,000 mark. “I’ll get recognised at one kebab shop and I’ll think I’m famous,” he laughs. “I hang out with Amy for five minutes in public, and it’s immediately like, ‘nup, she’s famous.”

Of course, with the band’s rising profile has come a fervent degree of discourse from different corners of the community. More mainstream outlets are put off by the band’s rabble-rousing, or by Taylor being her typical larrikin self on Spicks & Specks and calling Agro (yes, that Agro) a cunt at the ARIAs. To the “tru punx,” Amyl are seen as pop stars — cogs in the industry machine, with ARIA ticking off yet another alleged diversity quota. Their Gucci sponsorship, too, made them sell-outs of the worst kind. That’s all before you’ve even mentioned the word “sharpie,” which is a whole can of worms unto itself.

“The amount of times I’ve just been having a drink at the pub, and some cunt has come up and been like, ‘You’re a shit guitarist.'”

Taylor wasn’t wrong when she said you can never win. So, when Taylor and Martens are asked what they feel to be the biggest misconceptions or misunderstandings surrounding the band, they both come at it from different angles. For Martens, it’s a matter of legitimacy.

“We were so weird to people when we started, a lot of people assumed that we were just putting on an act, or that we were playing characters,” he says. “I doubt you could have found someone in Melbourne who was more into sharpie fashion than I was when the band started. It became really popular after the fact, but I was just on a wave of it. I was only ever being myself, but because it became popular people always want to question your motives.

“People always want to hate on you for doing your own thing. The amount of times I’ve just been having a drink at the pub, and some cunt has come up and been like, ‘You’re a shit guitarist.’ It’s like… cool? I didn’t ask for your opinion. The joke’s on you, mate — I’m literally getting paid to play guitar, and you’re not. I don’t care what you think.”

Photo Credit: Jamie Wdziekonski

Having seen plenty of tall poppy syndrome affecting so many bands and artists from Australia — something that has stunted the growth of countless acts over the years — Martens truly empathises with their plight. “I would hope that if there were other Australian musicians — not even in our genre — that were going through the same thing, they would feel so supported,” he says. “When you’re Australian, it can feel so small when you’re just playing around the country. When you get out overseas, though, you just realise how few bands from here actually make it to that point. We’re so under-represented on a global scale. I think Australia should really work on encouraging everyone who gets there.”

For Taylor, the bone she has to pick derives from being told what Amyl & The Sniffers is, rather than the band dictating it for themselves. “Punk, really, was something that was put on us,” says Taylor. “We always thought we were just more of a garage-rock band. We were just stuffing around when we started — we were 20 years old, and we didn’t know much of anything. So when people started being like, ‘oh, well they’re a punk band, why are they playing this festival that’s not punk?’, that’s all through their own implications.

“Not that it’s any of their fuckin’ business, of course. This band is nothing more than what it actually is.”

“Not that it’s any of their fuckin’ business, of course. This band is nothing more than what it actually is. We started because we wanted to play a house show, and things just went well for us. Really, when people are squabbling about us, it’s about stuff on the peripherals.” Taylor does make a point, however, of noting that not all of the criticisms drawn towards the band over the years are entirely invalid — nor have they fallen on deaf ears.

“Sometimes, it’s beneficial,” she says. “I’ll hear criticism and just think it’s really mean, but then I’ll think about it and realise they have a point. Oh, I should learn more about this thing. Maybe I am holding my microphone wrong. I guess mass consumerism is fuckin’ bad.”

If there’s one thing Taylor wants people to know about Amyl, it’s that there’s no greater scheme afoot. “Stop fuckin’ pretending like we know what we’re doing — because we don’t,” she says.

“We’re fuckin’ humans! And we’re just fuckin’ existing! People have really backed us from the start, and have been super supportive. That’s who we do this for. Judgement isn’t a bad thing at all. Judgement just makes you better, and I’ve copped heaps of it. I’m just gonna be a weapon, and anybody who’s been sleeping on me? I feel sorry for them, because I’m gonna do some sick shit.

“I’m gonna have the last laugh.”

David James Young is a writer and podcaster. He looks forward to throwing ‘bows and shooting index fingers up into the air when Amyl are finally allowed to play a show again. He Instagrams at @djywrites.

Photo Credit: Jamie Wdziekonski