In Defense Of Pacific Rim

A Hollywood blockbuster with feels.

It’s a Hollywood truism that blockbuster movies are aimed at 13-year-old boys. The system is broken, and audiences are being ‘treated’ to rehashed franchises, indulgent star vehicles, and troublingly endless, consequence-free death and mass destruction.

We’ve learned to regard cinematic spectacle as a kind of dull, widescreen blamminess to which we can only react with childish glee. So I worried that Pacific Rim’s central premise — ‘alien monsters vs giant robots’ — was yet another juvenile blockbuster-by-numbers. The mixed critical reaction and “grim” overseas buzz wasn’t exactly promising, and even the presence of director Guillermo del Toro (Pan’s Labyrinth, Hellboy) didn’t raise my expectations.

But I fell in love with Pacific Rim, so deeply it took me by surprise. It’s brilliant. I couldn’t keep the smile off my face the whole way home. It did what many movies seem to have forgotten. It made me feel.

A World That Feels Real

Pacific Rim is set in a near future in which alien monsters called Kaiju (Japanese for ‘monster‘) have emerged from an interdimensional rift beneath the Pacific Ocean to devastate coastal cities. Humans fight them in skyscraper-sized robots named Jaegers (German for ‘hunter’), motion-controlled by pilots via a neural interface.

If this sounds ridiculous, consider that people in the Pacific Rim already live with the ever-present threat of earthquakes and tsunamis, that the kaiju movie genre was invented to exorcise the horrors of the Hiroshima and Nagasaki nuclear attacks, and that Japan’s post-WWII recovery was led by its technology sector.

Like pro wrestlers, each Kaiju and each Jaeger comes to the film with names and backstories. There’s Cherno Alpha, the tank-meets-nuclear-plant Russian Jaeger; Crimson Typhoon, the lacquered, gleaming Chinese Jaeger; Striker Eureka, the camouflage-painted late-model Australian Jaeger… And, of course, Gipsy Danger, the American ‘hero’ Jaeger. Its streamlined curves and riveted steel plates recall WWII fighter planes — even down to a pinup girl mascot — thus accessing a wealth of cinematic subtext (Top Gun, Memphis Belle) about heroism, risk-taking and camaraderie.

I’m sick of watching near-invincible protagonists and antagonists endlessly slug it out in breakneck-edited sequences, on screens so dizzyingly stuffed with hyper-detailed CGI artefacts that the eye can’t locate a focal point — a style my friend Paul Anthony Nelson calls “digital confetti”. So I loved that you can see the pistons and gears driving these CGI colossi to match the deliberate, balletic movements of their human pilots. Their battles against the Kaiju have a choreographed narrative that’s lacking in most dreary, destructive movie slugfests. The Jaegers may be immensely strong, yet they’re also vulnerable, and there’s a real sense of risk to every clash.

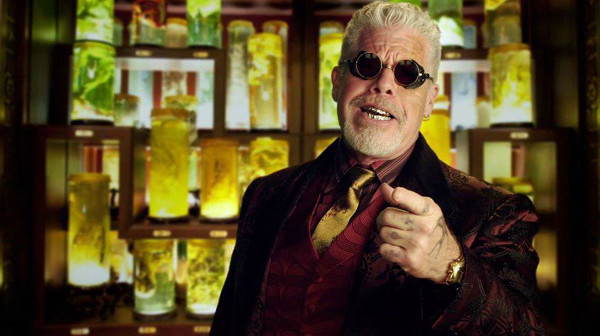

Meanwhile, human culture assimilates the new reality. The skeletons of downed Kaiju become religious shrines. Like bear bile and tiger penises, their biological material is sold on a medicinal black market controlled by the wily Hannibal Chau (Ron Perlman).

The film left me hankering for more time in this universe. A graphic novel prequel fills out early wartime events; I want to read it so badly!

A Film With An Emotional Core

Contemporary action blockbusters are told through a language of detached, macho posturing. We’re invited to find things ‘cool’ and ‘badass’: slick costuming, quippy dialogue, swooping camerawork, daring stunt sequences, and a general mood of insouciant bravado in the face of mayhem.

You’ll find these things in action movies because they offer real viewing pleasures. The recent Fast & Furious 6 did preposterous posturing so well it repeatedly sparked spontaneous applause in my audience. But these shouldn’t be the only feelings blockbusters inspire.

I respect Pacific Rim’s romantic sincerity: its refusal to ironise human heroism. We’re cynical about themes of ingenuity and cooperation, rousing speeches and honourable battle deaths, because they’ve become such hoary cinematic clichés. Paul Verhoeven’s Starship Troopers cleverly satirises the way that war makes fascists of us all, while the ‘Star-Spangled Man With A Plan’ montage in Captain America: The First Avenger gently pastiches the hokey artificiality of wartime propaganda.

Yet this film accesses a childlike, pre-ironic sense of joy and wonder. Its cheesiest B-movie moments display a zest lacking in such ‘grim nerd’ fantasies of angst, alienation and fear as Iron Man 3, Star Trek: Into Darkness, Man of Steel and The Wolverine. Even the distractingly fake Australian accents sported by Striker Eureka’s pilots Herc Hansen (Max Martini) and his son Chuck (Robert Kazinsky) make sense in this context.

“Today there is not a man or woman here who shall stand alone,” speechifies Stacker Pentecost (Idris Elba), Marshal of the Jaeger program. (I appreciated that screenwriters Travis Beacham and Guillermo del Toro eschewed militaristic ranks for Wild West terms like ‘marshal’ and ‘ranger’.) In this film, cooperation is a human ideal worth fighting to protect.

A Romance Without Sex

Jaegers require two simultaneous pilots, but few have the deep personal bond needed to initiate a ‘neural handshake’ and enter the state of shared consciousness the film calls ‘the Drift’.

Our hero Raleigh Becket (Charlie Hunnam) pilots the Gipsy Danger with his brother Yancy (Diego Klattenhoff). He’s shocked and traumatised when Yancy is killed on a routine Kaiju skirmish — not just because he vicariously experiences his brother’s terrified death, but also because the Jaeger program has falsely believed itself invincible.

Five years on, Pentecost convinces a jaded Raleigh to join the remaining few Jaegers in a last-ditch mission off the coast of Hong Kong, where he immediately sparks with Pentecost’s assistant, the mysterious Mako Mori (Rinko Kikuchi). She’s Raleigh’s obvious replacement co-pilot, but why won’t Pentecost let her try?

Stories that use mind-melding as a metaphor for human connection — such as the recent Stephenie Meyer alien-possession drama The Host — are often belittled as banal sexual fantasies for teenage girls. Even the idea of being moved by something — or in Tumblr parlance, experiencing ‘the feels’ — is derisively feminised as fangirl behaviour.

Hunnam’s performance is serviceable without being especially charismatic — which is kind of fascinating. Like Michael Biehn in The Terminator, Keanu Reeves in The Matrix, Sam Worthington in Avatar and Garrett Hedlund in TRON: Legacy, he’s a bland hunk whose appeal lies in the physical power and emotional closeness bestowed by a human-machine interface.

But Pacific Rim’s central pairing is tender and intimate without relying unduly on the spectacle of Hunnam’s body or the Hollywood trappings of erotic romance. Mako is an action heroine who isn’t a foil, a ‘strong female character’, but a flawed person in her own right. She and Raleigh work towards a shared purpose, strengthening each other not through sex, but through implicit trust. For those who believe in soulmates, it’s an irresistible proposition.

–

Mel Campbell is a freelance journalist and cultural critic. She is the founding editor of online pop-culture magazine The Enthusiast and the national film editor of the Thousands network of city guides. Her debut book, Out of Shape: Debunking Myths about Fashion and Fit, is out now through Affirm Press.