‘Get Out’ Is Even Better Than Woke White Critics Have Told You

Get Out is smart and silly, wry and angry, of the moment and steeped in history. It's also much more than the satire of white liberalism it's hailed as.

Get Out is a masterpiece. It doesn’t just walk the tightrope between horror and comedy, it does cartwheels and pirouettes on the wire before nimbly vaulting back and forth between the two.

It is smart and silly, wry and angry, of the moment and steeped in history. It works on so many levels it could double as an elevator, in a pinch. It is also much, much more than the satire of white liberalism it is ecstatically hailed as being.

The set-up is deliciously simple: a white woman brings her black boyfriend home to meet her parents, but something is very wrong. It would be easy to say there’s a bit of Guess Who’s Coming To Dinner in there, or a bit of The Stepford Wives, but there’s more to it than shared DNA.

Under the assured writing and direction of Jordan Peele, Get Out doesn’t just riff on those films, it takes their lessons — race relations are fragile and frayed, suburban civility is a mask for all manner of controlling evil — and goes deep into the murky territory beyond.

A great many reviews of the film, however, are of a similar tenor; it “gives middle-class white liberals a thorough skewering”, it “takes a razor-sharp scalpel to white liberal attitudes on race”, “it’s a sharp take on the scary world of stuff white people like”. You can understand the temptation for the overwhelmingly white critical fraternity to view it through their lens — what better way to prove how woke you are than to laugh at yourself, to eagerly point out that a film this pointed is pointed at you?

It’s just another way to erase the black perspective — the minority experience — from one of its rare positions on centre stage.

White Noise

Conceptually, Get Out works because of the way a great many people react to interracial relationships. At the very least, they’re seen as unusual, and cinema is rich with the complications thereof — never mind Sidney Poitier films, they’re even coded into storied American monster movies. To quote the poet Kanye: “They see a black man with a white woman /At the top floor they gone come to kill King Kong.”

All of this is roiling in viewers’ heads when Chris (Daniel Kaluuya) and Rose (Alison Williams) pull up to her parents’ home. The casting is tremendous throughout; Williams is cool and confident in a bigger role than is first apparent, while Kaluuya’s weary, soulful, knowing performance knits the whole film together. He’s particularly good whenever he plays off Rose’s parents — Bradley Whitford and Catherine Keener, for so long the beloved on-screen voices of reason and respectability, give every scene they’re in a slick, unctuous sheen.

They’re so eager to make Chris feel like he belongs that they only end up emphasising how much he doesn’t. A stream of microaggressions turns into a raging torrent when it turns out the couple’s visit is on the same weekend Rose’s parents are playing host to a party of like-minded neighbours.

Increasingly isolated, Chris absorbs or bats away the smaller indignities, before succumbing to the eternal, internal gaslighting undertaken by so many people of colour in an effort to normalise similar situations — did they really just say that to me? Did that really just happen? Is it worse if they meant it, or if they didn’t?

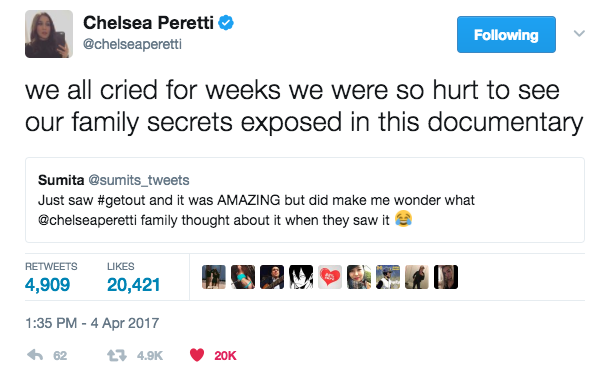

A tricky question, that last one; two sides of a blade thin enough to fit under fingernails. It is the height of privilege to assume that Get Out is about white privilege, or the edification of white audiences; it’s precisely that element of subjugation and subordination that is being parodied. But the exquisite awkwardness of the white characters’ reaction to having a black man in their midst, and Chris’ resulting pain and uncertainty — that’s not satire, that’s a documentary. We laugh because it’s horribly, terrifyingly real.

Keep Your Eyes Peeled

It’s frankly ridiculous that this is Jordan Peele’s directorial debut. He’s built up an impressive, eclectic resume outside his stellar work on Key & Peele, but nothing that suggested just how good Get Out would be. This is a work that celebrates and subverts its genre(s), one that has emerged, fully formed, to announce the arrival of a major voice.

It’s Peele’s mastery of tone that makes the biggest impression. He ratchets up the creepiness and lingers on the levity just long enough to deliver a thrum of anticipation each time he switches gears. Get Out mostly takes place in broad daylight, in the huge, high-ceilinged rooms and outdoor entertaining spaces of the rich and famous, but still manages to convey a relentless claustrophobia. Chris reaches out to the few people of colour in the overwhelmingly white world he’s visiting, only to find they’re off, somehow. He’s trapped and alone. Segregated, you might say.

The creepiness is so constant, so pervasive, that the third-act revelations — and you better believe there are revelations, as satisfying as they are gruesome — act as a kind of catharsis.

There is a pressure valve, however. Chris’ friend Rod, a TSA officer played by Lil Rel Howery, first comes across as yet another wacky minority supporting character, but Peele is far too savvy for that. He knows what the audience expects from Rod, who’s allowed to be funny as hell — but Rod is also competent and observant.

There’s a great scene in which Rod articulates his fears for Chris’ health to three POC police officers, only for them to laugh in his face. It’s the closest the film comes to a lesson — whether it’s pigmentation or a light sheen of buffoonery, sometimes the hardest thing to do is see past the facade.

Race To The Finish

It’s a quirk of timing that Get Out arrives in the early days of the Trump administration, and that it follows on the heels of films like Loving and A United Kingdom, historical dramas dealing with interracial relationships. For all the struggle depicted in those films, there’s something straightforward about them, a clear-eyed take on love triumphing over the odds.

Get Out is what happens after the credits; it’s the very personal brainchild of a mixed-race filmmaker in a mixed-race relationship who knows just how messy they can be. To depict that cavalcade of loose ends and uncertainties in a film this taut, all the while commenting on the jagged subtleties of cultural appropriation and racial fetishisation, is just extraordinary. And that’s before the blood starts flowing.

Get Out isn’t going to solve or salve racism. It’s not going to erase prejudice, or build bridges where there were none before. Its value comes not just from its heartbreakingly rare emphasis of a perspective so often trampled and shackled, but its appeal to anyone who has ever been alienated in social situations or workplaces or out walking on the street — even if the particulars of the minority experience are different, there is a vast continent of common ground to explore.

This flip side works, too: it’s not just a certain shade of liberalism that’s being lampooned here, it’s the fervour of allies so desperate to prove their bona fides that they end up consuming and subsuming the very voices they’re meant to be supporting. Fetishisation can be as harmful as bigotry, it says; and when you’re told to get out, run.

—

Get Out is in select cinemas now and will have a general release on May 4.

—

Hari Raj has worked as a journalist and editor in Malaysia, China, and Australia. He tweets about pop-culture ephemera at @jarirah.