Flea On Drugs, Death, And Why He’s Never Read ‘Scar Tissue’

"It took quite a while to figure out that the hangover was worse than the high was good, that it was a losing bargain, and stop."

There are plenty of disturbing moments within Flea’s new memoir, Acid For The Children, but there’s one in particular that sticks out.

— Content Warning: This article discusses drug abuse and child abuse —

It comes about a third of the way through, when Flea — born Michael Peter Balzary — was just a young teenager in LA, spending his spare time skating around Hollywood and smoking weed with his friends. One day he was out on his paper run when a man answered his door and introduced himself as ‘Elmo’, and said he was a talent scout for Paramount Pictures. He told Flea he was a natural for the movies, promised to make him a star, and invited him back next week for a ‘slumber party’ with a group of neighbourhood kids.

Flea’s mother let him go (“In retrospect”, Flea writes, “it is absolutely fucking insane that my mother had no objections to me going”) and so he went. On the night, Elmo asked Flea to strip down to his underwear and lie on his back in bed, so as to let the “white spirits, the good spirits” enter him.

“I was frightened of everything,” he writes. “I imagined diving through the bedroom window to escape. I felt completely duped.”

Somehow, the 13-year-old managed to fall asleep while Elmo — also in his underwear — slept beside him. The following day he raced away on his bike; he never saw Elmo again, and he never told anyone about what happened until he decided to write about it in his memoir.

“It was just one of those things where I’m writing about being a street kid growing up in Hollywood, getting into all kinds of shit — and it was dangerous, this was Hollywood in the ’70s, it was dangerous,” Flea says, over the phone from the States. “[That incident] was an important part of the danger that I felt as a kid in Hollywood. It was the colour of my growing up.”

A young Flea.

If you come to Acid For The Children hoping for a Vol. 2 of Anthony Kiedis’ drugs, sex, and rock ‘n’ roll-soaked memoir Scar Tissue, you’ll be disappointed. In fact, if you’re hoping for any Red Hot Chili Peppers antics, you’ll come away wanting — the book ends shortly after the band forms. What Flea instead offers is an intimate and eye-opening examination of his childhood, from his early years in Australia, to moving to New York and his parents’ split, to finally landing in Hollywood and becoming consumed in its street punk culture.

“I originally I thought I would only write about the band because I thought it would be arrogant to write about my own personal story,” he says. “But then as I started writing, I realised I didn’t want to. Writing about the Chilli Peppers would be…it would only be my perspective about, you know, what happened when we made the records and the tune of that piece, and this emotional moment and this traumatic moment and this exciting triumphant moment.

“But if I could write without the Chilli Peppers,” he continues, “and just write about my childhood and write something that was good, then it would actually have a chance of being a piece of literature on its own.”

Flea’s writing, like the man himself, is compelling — he’s tender and vulnerable at many points, constantly examining his younger self’s motives and actions. He didn’t use a ghostwriter, and he was led through the project by renowned editor David Ritz, who helped reel in some of Flea’s more outlandish imaginative wanderings. Some of them still slipped through — the opening passage about him crying, overwhelmed by music in Ethiopia, is a little trite — but there are also genuinely heartbreaking passages, such as when he writes about the drug addiction and death of original RHCP guitarist Hillel Slovak, and his volatile relationship with frontman Anthony Kiedis.

Kiedis is a vivid, central figure throughout the memoir, and you get the sense that, even decades on, Flea is still trying to reckon with the power of their relationship.

Kiedis is a vivid, central figure throughout the memoir, and you get the sense that, even decades on, Flea is still trying to reckon with the power of their relationship. “The way I bonded with my friends had always been intense,” Flea writes. “But with Anthony, it was next-level shit — the spirit of adventure, the street hustle, the getting high, the art, the philosophy, the burning desire to make something happen. Nothing I did freaked him out, and I’d freaked out every friend I ever had.”

“I think the understanding that I have now of [our relationship] is that I don’t understand,” Flea says, after a long pause. “I understand that I love him and that he loves me. I’s the sort of relationship that has its conflict and its anxiety and its disagreements and its different ways of seeing the world. It’s difficult and it’s always been that way. We’re very different people. We have different aspirations, we have different, you know, just different methods about life, you know.

“I can’t remember exactly how I word it in the book, but I said that if I did understand it, maybe all the magic and the energy would leak out of it. And I think that is kind of the thing now, you know sometimes it’s like a magic trick when you see how it works, it’s not magic anymore, you know?”

Anthony Kiedis and Flea.

Flea says me he didn’t intend to write about Hillel’s death, but it became unavoidable as the wild guitarist was a permanent and important fixture in his life. It was Hillel, for instance, who first pointed Flea in the direction of the bass. Avoiding writing about his death in 1988, despite the book ending before that year, was simply not an option.

“Once I got to that point in my story, where I started writing about how Hillel came into my life and about how he and I and Anthony became this threesome, it was impossible not to,” Flea explains. “It was kind of inseparable from his life. He’s been gone for so long now, I mean he’s been dead for 31 years. Every time I wrote about him I thought about his death as well. I just wanted to write about our experience together then, but it was just kind of like inextricably wound together, his life and death.”

“Did he feel death coming when he shot that last dose of smack? An enveloping darkness? Did he drift away painlessly into a pleasant ether?”

In the book, he recounts the moment he heard of Hillel’s death — how he’d come home to a phone ringing off the hook, the Chili Peppers’ manager Lindy Goetz desperately trying to get a hold of him. “I crumpled to the floor,” he writes. “I wondered what it was like for Hillel on that hot smoggy day…did he feel death coming when he shot that last dose of smack? An enveloping darkness? Did he drift away painlessly into a pleasant ether? Did he panic as life drained away?”

The passage is difficult to read, as is the brief description of his funeral.

“I wish that I would’ve been more evolved so I could have helped him better when he was really struggling,” Flea says now. “I feel a lot of sadness and an incredible sense of loss — and much more than the sadness from the loss is that I feel a massive, intensive appreciation for getting to appreciate him while he was alive and just for the absolute beauty of who he was. You know, the artist, the poet, the comedian, the friend, the dancer, the lover, the beautiful man that he was. And I just feel really, really grateful that I got to share his life with him for his brief time here.”

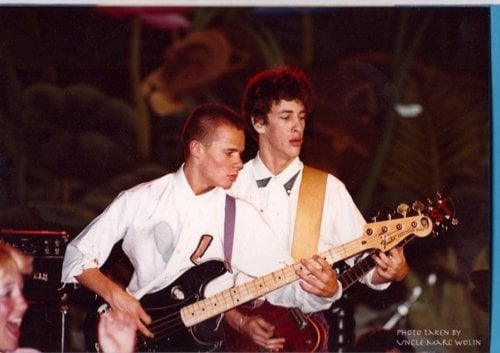

Flea and Hillel Slovak.

“I was too ambitious and excited by the things I loved to ever become a junkie,” Flea writes, not long after the passage about Hillel’s death. “It took quite a while to figure out that the hangover was worse than the high was good, that it was a losing bargain, and stop.”

He may never have been an addict, but drugs are still everywhere in (the aptly titled) Acid For The Children. Weed is a constant, as is cocaine, crack, and amphetamines. In one chapter, titled ‘Here Come The Geezenslavs’, he details the way he and Kiedis would scam pharmacists for syringes they could use to inject coke — he also goes step-by-step through the preparation process, describing the moment you know the drug has properly entered your vein. But somehow, miraculously, Flea escaped the worst.

“Through all of that, like believe it or not, I never got addicted to drugs,” he says. “I experimented wildly and to the point that I really hurt myself with it. I wanted to write about that, about the absurdity and the craziness of that because it was a big part of my fucking life. At the same time, I didn’t want to glorify it because there’s nothing glorious about it. And I’m not proud of it, you know? But I felt like this is a part of who I was. I started doing drugs at a very young age, I spent a lot of energy on getting them, doing them and recovering from them. And it’s a big part of my story.”

Red Hot Chili Peppers

Flea hasn’t read Anthony Kiedis’ Scar Tissue — although he might now that he’s written his own book. But for a long time he ignored it, only occasionally picking it up and getting pissed off at its contents.

“He and I can sit in a room and have a talk and we’re both going to walk out of it and have a completely different view of what happened in that room,” he says. “Because we’re completely different people and I decided it would be very difficult to read about the shared experiences from his perspective.

“I don’t know why that’s difficult for me. It’s just hard. I picked it up once and looked at it a little bit and I was like ‘Oh, that’s cool that you said that,’ and I read another part and was like, ‘Why did you say that? What the fuck?’ You know what I mean? I didn’t want to have to walk into a room and record with him and have these conflicted feelings about our different viewpoints from our lives.”

He’s not sure whether Kiedis will read Acid For The Children — he’s not concerned with that. At the moment, the only thing he’s hoping for is something that he hopes for with every piece of art he makes — that people feel less alone when they experience it.

“My childhood was very difficult in many ways and not very difficult compared to many,” he says. “Pain is a source of growth. And that anxiety and that difficulty and that sense of feeling disconnected, it’s energy. And if you can transmute that energy into creative energy, if you can turn a difficulty into light, you can share it with other human beings and make the world a better place. That’s my great hope.”

Acid For The Children is out now through Hachette Australia. Photos courtesy of Hachette Australia

Jules LeFevre is Editor of Music Junkee. She is on Twitter.

For information relating to drug and alcohol addiction, or if you or someone you know is struggling with addiction, call the National Alcohol and Other Drug Hotline.