Everything You Should Know Before Sticking A Bindi On Your Head

This debate has been going for a long time; why are so many white people still wearing them to our festivals?

I spent a really long time trying to work out how to start this article.

I thought about the time I was 12 and proudly wore a bindi to school every day — a ritual I soon abandoned for fear of looking too ethnic. Or the number of times I’ve struggled to broach the topic of bindis and paint-on third eyes to friends who regularly wear them to festivals or parties. Then, on a recent Saturday night, inspiration struck in the unlikeliest of places. I was sitting at a swanky inner-city establishment with a group of (mostly Indian) friends when two women walked in and approached the bar.

“Hey,” I whispered. “She’s wearing a bindi”.

We all turned to gape. Affixed between this white girl’s eyebrows was a sparkly blue bindi.

The entire scene was like something out of a Hatecopy print.

Let’s Talk About Culture And Context

Many South Asians born and raised in the West have a complex relationship with their ‘Indianness’. For many of us, learning to be comfortable in our own skin is a long and often painful process. So it can feel slightly awkward watching people with no obvious connection to South Asia publicly engage with elements of our heritage when we wouldn’t do the same.

‘Cultural appropriation‘ is a common grievance among members of our socially conscious generation. Simply defined, cultural appropriation refers to the adoption of elements of one culture by another. At first glance, it’s easy to see why this may not seem so big a deal. Culture is fuzzy and complex. Cultural groups have long borrowed various customs, practices and symbols from one another. But the problem arises when the cultural groups in question do not, for whatever reason, have an egalitarian relationship. The nature of this relationship can transform a seemingly innocent act of cultural borrowing into more sinister one of exploitation.

When it comes to cultural appropriation, context is everything. For example, when someone without Native American heritage wears a headdress to a festival or a Halloween party, they claim ownership of this symbol for themselves by detaching it from its historical context and simultaneously erasing its cultural significance. This process of detachment and erasure contributes to the systematic oppression of First Peoples and the destruction of their cultures. This is not to say that borrowing from indigenous cultures is always offensive; but the special significance of the headdress makes it off limits to cultural outsiders.

But while most would agree that wearing a headdress amounts to cultural appropriation, opinion on the bindi isn’t so straightforward. This may be because not everyone agrees on what the bindi symbolises. In India, bindis are widely worn by women from many different religious and cultural communities, including Hindus, Jains, Sikhs, Buddhists and Catholics. Some believe it is linked to the third eye, or ajna chakra, a site of wisdom and power said to be situated between the eyebrows (this is why I’m also uncomfortable with third eye face paint). Others associate it with married women, though it is also commonly worn by children and single women. Parents may also mark their babies’ faces with bindis to ward off the evil eye.

Nonetheless, some argue that the religious significance of the bindi is lost on many South Asians today, meaning that it’s not such a big deal if other people wear it without understanding its cultural significance too. This is a pretty contentious claim, and one I personally believe to be untrue. This aside, I feel that this argument kind of misses the point. It could be said that wearing a bindi for purely aesthetic reasons, without any connection to South Asia or South Asian religions, erases its history and transfers its ownership to cultural outsiders. At times, this can feel a little unfair.

Many Indian cultural practices were shunned or prohibited over 200 years of British colonisation. And for South Asians living overseas, publicly celebrating our cultures can be uncomfortable, or downright scary. Despite strongly identifying with my Hindu Indian heritage, I wouldn’t consider wearing a bindi in my day-to-day life for fear of being treated differently, or even vilified — not an unreasonable fear in these times.

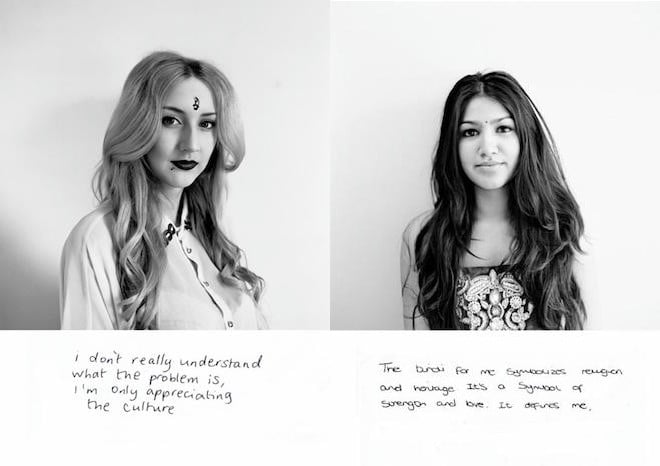

Image via Sanaa Hamid/NY Daily News.

Fans of the bindi may also be drawn to the romantic appeal of Hindu or South Asian culture. This is a little unsettling. Our cultures have long been fetishised and gravely misunderstood in the West. Hinduism is often romanticised as a wholly inclusive, tolerant and peaceful religion. As within nearly all other religious traditions, this may be true of some — but definitely not all — of its strands. Even Hindus (especially those of us who are physically far away from its consequences in South Asia) sometimes forget its more problematic elements.

Of course, there are many non-South Asians who have genuinely engaged with these traditions. But there are also many who have not, while happily donning bindis, practicing yoga and hanging Ganesha tapestries outside their festival tents in a performance of Indianness that few Indians would recognise. Failing to genuinely engage with the history of these cultural products just contributes to the cycle of exoticisation. It’s a little dehumanising. As Melbourne-based writer Kamna Muddagouni states, “a wider ignorance about Hinduism and South Asian culture […] when you’ve spent a fair amount of your formative years being othered, can hit home hard”.

Right, Wrong And The Space In-Between

Still, I wouldn’t say that wearing a bindi is always bad. Remember, context is everything. Wearing a bindi at a Hindu wedding is pretty different to accessorising with one at a bush doof.

Why? The former scenario involves a space dominated by Hindus and/or South Asians that facilitates a celebration of our cultures on our own terms. In this context, you’re not exerting ownership over the bindi if you choose to wear one, as you have been invited to participate in our rituals and are making a concerted effort to meaningfully engage with us. In the latter scenario, you’re wearing the bindi in spaces that are not ours, and that often exclude us — thus completely separating it from its cultural history and significance — and from us.

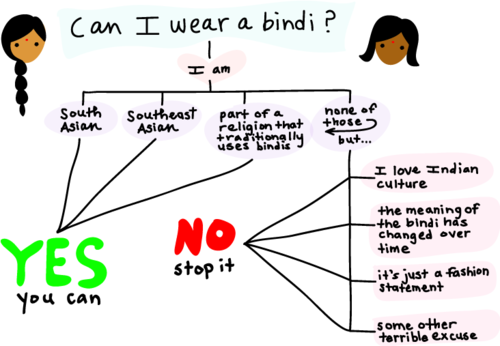

So who can wear a bindi, and where? Unfortunately, there’s no simple answer to that question. A number of South Asian women writing on this subject have formulated their own criteria for acceptable usage of the bindi. Aarti Olivia suggests that a non-South Asian may wear a bindi if they are either getting married to a South Asian, or attending an Indian festival or ritual. Meanwhile, recognising the broader cultural significance of the bindi, Reclaim the Bindi suggests that all South Asians, including those who do not have Hindu heritage, may wear the bindi at their own discretion.

Picture via Reclaim The Bindi.

I find it more useful to use these suggestions as just that — suggestions, or rough guidelines for behaviour, rather than steadfast rules. It is literally impossible to come up with an exhaustive list of acceptable situations for wearing a bindi. I would also argue that providing such a list would place the onus to protect against offensive behaviour on those who are offended — which is both really annoying, and would do little to tackle complacency around these issues in the long term.

I suggest a better approach is to encourage a general attitude of engagement, reflection and respect. Be curious, ask questions, do your research. Understand your position and be mindful of the impact of the decisions that you make. What is your understanding of the bindi? Why are you wearing it? Is your behaviour likely to cause somebody pain or discomfort? Are you contributing to a wider culture of disrespect or dispossession that you would otherwise not support? And sure, if you decide to wear a bindi anyway, not all South Asians will be offended. But some definitely will. And to me, that’s enough of a reason to err on the side of caution.

And if you’re currently cringing because you wore a bindi to a bar last week, don’t worry about it. We all do silly things. Just next time, maybe don’t.

–

Feature image: Maria Qamar/Hatecopy.

–

Vidya Ramachandran is a writer and law student from Sydney, interested in race, ethics and identity. She is passionate about Zadie Smith and pasta.