Cook And Sing For Us, But Don’t Date Us: What Reality TV Tells Us About Australia And Diversity

The Bachelor has been slammed for a lack of diversity, but why is it so white compared to MasterChef and The Voice?

Channel Ten ramped up the hype for the latest season of The Bachelor over the weekend by releasing details about the 22 women vying for the affection of Matty J.

Here they are:

Notice anything in particular about this year’s contestants? Nothing yet? Ok, try taking a look at the cast of the last US season of The Bachelor and then see if anything about the Australian version stands out.

Yep, the Australian version is extremely white. It’s pretty hard to argue that this year’s contestants are reflective of a country where, on a conservative calculation, more than 22 percent of the population has Asian, Pacific Islander, African, South American or Indigenous Australian ancestry, according to the census.

To be fair to the show’s producers, there is one contestant, Elora, who is from Tahiti. This is the incredibly chill way they’ve chosen to promote her:

~exotic~, ~mysterious~… ~ethnic~

Of course The Bachelor isn’t unique in its failure to accurately represent Australia’s cultural diversity. A Screen Australia report from last year found significant underrepresentation across a range of demographics when it came to scripted dramas.

But the issue is more complex than “Australian TV has a problem with race”. Shows like Masterchef and The Voice seem to do a pretty good at reflecting the real Australia on TV. So what’s going on with The Bachelor and why should we even care?

We Cook, We Dance, We Sing

Kirsty de Vallance, Australia’s best known casting agent, told the ABC last year that the issue of diverse casting on TV “all changed when the very first MasterChef series was cast”. “It was the first time I can remember that we had more than just a token person of an ethnic background,” she said.

The first two seasons of MasterChef featured popular contestants from diverse backgrounds like Poh Ling Yeow, Tom Mosby, Marion Grasby, Adam Liaw, Jimmy Seervai and Alvin Quah. Most of those contestants have even managed to parlay their stints on the show into longer-term media careers.

More recent seasons of MasterChef have upped the diversity benchmark even further, and this year’s winner was Malaysian-born Diana Chan.

The cast of the last season of MasterChef.

MasterChef serves as a pretty stark contrast to most other prime-time Australian TV shows, especially scripted comedy and dramas. TV producers seem so desperate to maintain cultural homogeneity on-screen that there’s also been a wave of recent White Australian biopics from the 1970s and ’80s (House of Bond and Hoges: The Paul Hogan Story are recent examples).

My Kitchen Rules on Seven has attempted to mimic MasterChef’s successful casting in recent seasons. Last year’s winners were the Indonesian-born sisters Tasia and Gracia.

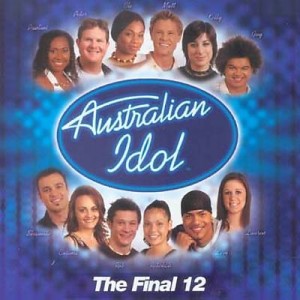

But MasterChef doesn’t deserve all the credit. The first season of Australian Idol, back in 2003, was like an ethnic hand grenade dropped into the bland, cauliflower soup of Australian TV.

Never forget.

Five of the 12 finalists in Australian Idol’s first season were people of colour, including Guy Sebastian, Paulini Curuenavuli, Levi Kereama, Rebekah LaVauney and Cle Wootton. That kind of diversity is still yet to be matched by shows like MasterChef.

Even though Australian Idol is no longer with us (RIP), its legacy lives on in shows like The Voice which feature similarly diverse casts, and was well represented in the long-running but recently axed X Factor. Australia’s two most recent Eurovision entries, Seoul-born Dami Im and Indigenous Australian Isaiah Firebrace, are both former The X Factors winners.

So when it comes to cooking and singing, Australian TV is all about cultural diversity. Which actually makes sense on a very fundamental level. There is absolutely no argument that the world’s greatest food comes from non-European countries.

Australia’s geographic proximity to Asia and our relatively high immigration rates post-World War 2 have helped make us the luckiest country in the world when it comes to sampling international fare. It would be very incongruous for shows like MasterChef to feature all-white casts when the best cuisine from places like China, Thailand, India and the Middle East is being cooked up in home kitchens across the country every night.

Diversity on screen has been quarantined to shows that feature the same traits people of colour have been stereotyped as exhibiting for over 100 years.

Similarly, the voices and music of people of colour have been considered highly lucrative since the earliest days of the recording industry. “The Negro trade is… an enormously profitable occupation for the retailer who knows his way about,” said an article published in 1926. Throughout the entire 20th century, black artists in particular formed the bedrock of the music industry’s most popular genres from jazz, the early days of rock through to disco, pop and hip-hop, even if they only saw a fraction of the profits.

Most recent pop songs are also heavily influenced by the music of culturally diverse artists, even if they’re sung by white singers. So, again, it doesn’t seem unusual to see so much diversity on shows like Australian Idol, The Voice and The X Factor. They’re reflective of an industry that basically fetishes people of colour, often exploiting them.

The problem we have at the moment is that it appears that diversity on screen has been quarantined to shows that feature the same traits people of colour have been stereotyped as exhibiting for over 100 years: cooking and performing for white people.

Why Won’t You Fuck Us, White People?

Let’s not beat around the bush. The Bachelor is a show that revolves around fucking. The bachelor wants to fuck. The contestants want to fuck. The audience wants to fuck the bachelor and/or the contestants. There’s no judgement here, it’s just the best way to summarise the show.

So when the show features an entirely white cast, the message being sent by the producers is that Australians don’t want to fuck people who aren’t white.

There are going to people reading this article who will jump in at this point and say “Oh but the contestants are chosen by the bachelor! It’s not racism, it’s just his show!”. First up, if The Bachelor’s Matty J gets to pick 22 contestants and he couldn’t find one woman of colour he was vaguely attracted to then idk, maybe he’s kind of an alt-right dickhead.

Wow the cast of the new Bachelor is so diverse pic.twitter.com/AVcyB4Xuip

— Sally Rugg (@sallyrugg) July 24, 2017

But seriously, if you think a show has heavily produced as The Bachelor simply hands over its entire casting process to a horny 30 year old from Bondi you are dreaming. Yeah, I’m sure he organises all the absurdly OTT dates involving helicopters and castles himself as well. Every element of the show is meticulously produced to craft compelling television, including the casting. By looking at the way the show has been cast, we can understand the implicit messages the show’s producers are broadcasting.

Across six seasons of The Bachelor/The Bachelorette, only one lead has been from a culturally diverse background: Blake Garvey, whose father is African American. Only a handful of contestants from the show have been from diverse backgrounds too, and most are booted out in the early rounds. Out of the 34 people featured on both seasons of The Bachelorette so far, only one has been a person of colour, and he was eliminated in the first episode.

It’s a pretty marked contrast to shows like MasterChef, My Kitchen Rules and The Voice. The takeaway seems pretty clear: TV producers, and perhaps audiences, are happy with people of colour cooking and singing for them, but they’re uncomfortable with the idea of non-white people as realistic propositions for romance.

The kind of historical structures that underpin this dichotomy pre-date reality TV, and shows like The Bachelor are more symptoms of a problem rather than their cause — though that’s not really an excuse to woefully underrepresent the diversity of Australia.

While some shows deserves props for their casting choices, they’re far from perfect. My Kitchen Rules might feature contestants from a range of backgrounds but it also regularly puts them in extremely awkward situations. Like the time a Vietnamese contestant was asked to dance to ‘Gangnam Style’ after explaining to the other contestants how much he dislikes being compared to Psy.

On MasterChef comparing the diversity of the contestants to the three, male, white judges is jarring. I enjoy watching the show but there’s sometimes a weird neocolonialist element to seeing people of colour cook up traditional food and serve it up to three rich judges who will dictate their fate and livelihoods.

But hey, at least they’re giving us a go.

–

Osman Faruqi is Junkee’s News and Politics Editor. He tweets @oz_f.