This piece deals with Breaking Bad, and the first season of Better Call Saul. Expect some spoilers.

–

Operating in a suburban strip mall office filled with faux Acropolis pillars, and an inflatable Statue of Liberty on the roof, Breaking Bad’s Saul Goodman was a fast-talking, ambulance-chasing parody par excellence. Better Call Saul — the series’ prequel, which ended its first season this week — cleverly dodged the nudge, nudge, wink, wink pitfalls that trap many spin-offs, and emerged fully formed as a rich and satisfying hour-long dramedy.

If Saul was the clown in the Greek tragedy of Breaking Bad, Better Call Saul didn’t just give him his own sideshow, but built an evocative and fascinating origin story all his own.

Bett Call Saul will eventually explore his formative years studying martial arts.

–

Faking It And Making It

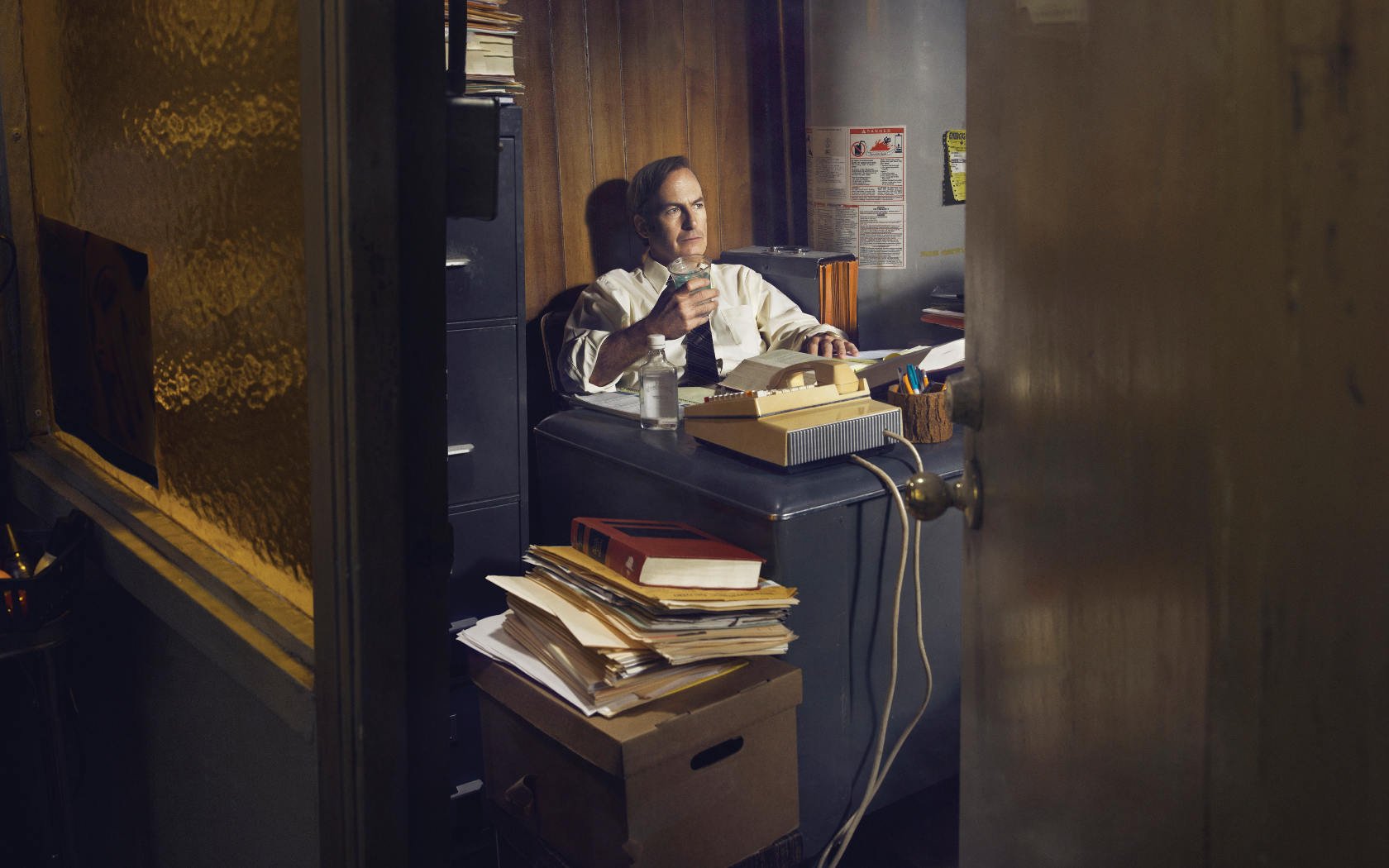

Better Call Saul begins not with the titular Saul Goodman, but with struggling defense lawyer James M “Jimmy” McGill. He works out of a storeroom in the back of a budget nail salon and answers his work phone in a high-pitched voice, pretending to be his own secretary. We see him working hard to defend his mostly hopeless and often hilarious clients, nebbishly rehearsing his arguments in a grimy city hall bathroom. Jimmy is sweet but pathetic, smart but ridiculous, Odenkirk’s expressive face caught in the permanently harried clench of the stressed and low status: a smile stretched tightly across his mouth, forehead sweating nervously with effort.

If this character seems too at odds from the Saul Goodman you know and love, there’s another, more familiar one hidden not too far in his past. Creator Vince Gilligan’s famed abilities with montage set to music are put to dazzling use: the soundtrack all sleazy bass lines and bright horns whenever we see the previous incarnation of James McGill, better known as ‘Slippin’ Jimmy’ – a con artist skilled at faking falls for insurance money and scamming money out of greedy strangers.

Money is a ubiquitous presence in Better Call Saul. Power, status and piles of cash are waved under the nose of Jimmy McGill, but they are never his own: he’s forced to argue and barter for every dollar and cent he earns. The only time it comes easily is when he’s Slippin’ Jimmy – and not coincidentally, it’s also the only time he has genuine friendship, and people who see him as more than a means to an end. Like Breaking Bad, a show about a man tipped over into crime and violence by a lack of affordable healthcare, Better Call Saul shows a man trying to do the ‘right’ thing in a system that’s less a meritocracy than it is a Rube Goldberg machine, powered by a hamster wheel.

Jimmy McGill: one part blaring late-night infomercial, one part Perry Mason, one part Lionel Hutz. Credit: Ben Leuner/AMC

Breaking Bad was a drama borne of a specific time and place – hinging on the lack of universal healthcare in suburban America, to pull the rug from beneath the deceptively precarious and hollowed out experience of routine middle class life. Walt’s journey from working two jobs and getting sneered at by rich teenagers in both, to reclaiming his purpose and building a meth-making empire, is a powerful narrative about the degrading inequity of late capitalism.

Better Call Saul’s Jimmy McGill is one rung lower on Maslow’s Hierarchy, and lives six years before the beginning of Breaking Bad, in 2002. The show does little to evoke the era, but in fairness, the era itself wasn’t evocative of much anyway. A scan of the year in review shows the most popular bands were Michelle Branch, Counting Crows and Coldplay: so far, so milquetoast.

Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs. In 2002, WiFi had hardly even been invented yet – it was a living hell.

2002 was also the immediate aftermath of September 11, and the shock of the attack had already mutated into a deep and anxious cultural and economic conservatism. This is the world in which Jimmy McGill is living. We learn that Jimmy’s brother, Chuck, has offered to rescue him from life as Slippin’ Jimmy in Chicago, and set him up with a job in the mail room at his law firm, Hamlin, Hamlin & McGill. Having worked his way up to becoming a lawyer by way of an online degree from the University of American Samoa, we see Jimmy’s confidence take hit after hit after hit. In a flashback, Jimmy’s office is not even an office, but a glassed-in copy room, where we see him and his one office friend, Kim, celebrate his finally passing the bar exam with a celebratory cake. In a scene almost as brutal as anything in Hannibal, we watch senior partner Harold Hamlin go in to speak with Jimmy alone and in complete silence, to break the news that Jimmy will be staying in the copy room for the foreseeable future.

Odenkirk’s face and body language say so much through the glass: his excitement and hope quickly curdling into such polite and professionally masked disappointment and, worse, acceptance that this is inevitable. The contrast between the two Jimmys is instructive: a con man in one life and a man completely lacking in confidence in the other. Jimmy even offers Hamlin a slice of his celebratory cake on the way out, and he takes it. A better metaphor for the privilege and entitlement of the wealthy ruling class over the workers I have never seen.

Presumably one of the founding partners of Hamlin, Hamlin & McGill.

From the vantage point of 2015, and with the foreknowledge of his future, watching Jimmy try to earn an honest living and make it in the snakes and ladders world of the legal profession is more than a little heartbreaking. His idea of “making it” seems so small, and yet is still somehow so unobtainable – a pathetic ‘cool’ kid’s club in the shape of a law firm full of arseholes in suburban New Mexico. When we first meet Walter White, he has already obtained the trappings of middle class success: a comfortable life with a family, a job and a house in the suburbs. Jimmy McGill, meanwhile, is still single and seeking the basics, like financial stability and somewhere to belong. Seen from a world where the Global Financial Crisis has been and gone, we know just how precarious even such a modest American dream is for someone living in the 99%.

From Mr. Chips To Scarface, To A Searing Comment On American Late-Capitalism

Gilligan is deeply interested in the twin dysfunctions of capitalism and destiny and the power of these forces in creating character. Walt takes only one push to turn from Mr. Chips to Scarface, his cancer a perfect metaphor for the greed for power and money that we watch slowly eat him alive. The transformation of Jimmy McGill to Saul Goodman is not such a straight line. Not interested in power over others, he falls over himself to ensure his sick brother is taken care of, works as a public defender for deadbeat teenagers, gives legal advice to the elderly residents of a care facility who are being cheated by management – even the ones who can’t pay his already cheap bills. Even as Slippin’ Jimmy, his marks are never the helpless – always people who were lured in and caught out by their own greed. While comedy often makes much of status games, his inherently low status is less funny than it is heartbreaking: Better Call Saul has a far deeper sense of good and bad than the simplicity of the legal world it lives in. Everywhere society’s systems are depicted, they fall short of the capacity of those within them to be taken advantage of or to take advantage. Jimmy McGill and Slippin’ Jimmy may seem opposite, but they are connected by a continuum: both deeply, if uniquely ethical, one working inside the system and one without.

The true tragedy of Jimmy McGill is one of Aristotelian proportions. He is “…a man who is not eminently good and just, yet whose misfortune is brought about not by vice or depravity, but by some error or frailty.” His frailty is an entirely human one: he just wants to get along with his life and be liked. He does not have the entitlement or ego or greed of someone like Walter White, or Harold Hamlin, or the clients who embezzle $1.6 million dollars. He doesn’t see money as a goal or amassed wealth as a destination he longs for: he doesn’t take advantage of his power when he has it, and he suffers for it.

At one point, a wealthy woman tells him why she won’t hire him as her lawyer: “It’s just… you’re the kind of lawyer guilty people hire”. The inherent classism and cruel snobbery cut through all of Jimmy’s machinations like a knife – and later push him to become someone very different to this man we see now. She’s saying he’s poor and he acts poor, and no one makes a mark in this deeply rigged game by aligning themselves with the powerless.

The audience already knows how Better Call Saul ends, but the show still manages to build a remarkable sense of possibility in Jimmy McGill. Having a character as strong and entertaining as Saul Goodman to build to, it takes impressive writing to create an almost entirely different person, and make us wish for things to turn out differently. From the slow erosion of his minimal confidence by his brother and the other legal partners, to the loneliness of his work as a lawyer trying to scrape together enough money to live to his constant position as the man on the outside looking in, Better Call Saul is a powerful evocation of the loneliness of trying to move from lower to middle class. When we see him in the finale with his old friend Marco, embarking on one last con in Chicago for old time’s sake (a remarkable American Hustle-esque montage set to perfectly Chicago razzle-dazzle, jumping jazz), the loving acceptance of Jimmy — not for who he could be or what he can do, but just for who he is — is as heartbreaking as it is frightening. We know how much he has to lose, but seeing a person treat him with kindness and love: what money or power is comparable to that?

For a character who served primarily as comic relief in Breaking Bad, the first season of Better Call Saul has built a complex, fascinating and deeply tragic back story in Jimmy McGill. His low status evokes not just black humour and ridiculousness, but the sense that power and privilege are strong forces made manifest in the people around him: operating on him from outside a glass cage that he can’t get out of. Class and destiny are inextricably entwined, and the system is constantly working against even the best of intentions by those within it.

For all the talk about Don Draper and Mad Men’s exploration of the American Dream, Mad Men’s newest AMC stable mate is the show that best captures the inversions and perversions of masculinity, ambition and self-actualisation in modern America. While Mad Men’s conceit relies on historical events and a certain unexamined impulse for rubbernecking at inherited nostalgia, it is elephant art. Better Call Saul is termite art: small but no less dangerous and even more powerful than an elephant, silently eating away at structures from beneath while the world goes on above, entirely unaware.

–

The first season of Better Call Saul is available to stream through Stan.

–

Courteney Hocking is a Melbourne writer and reformed comedian who has written for Good News Week, The Guardian, The Age & Crikey. She tweets @courteneyh