Video Games Show Us The Weird, Often Baffling Ways The World Imagines Australia

Media depictions of Australia feature harsh Outback landscapes as the norm and larrikin characters so laid-back they’re practically horizontal, but this tends not to capture the whole picture.

While many of us wear these bloody ripper stereotypes as a flamin’ badge of honour, particularly the adoption of dollarydoos as our national currency, there’s far more to Australia than what you see on a screen. It’s a big deal seeing ‘Straya depicted in a video game, even if our overseas mates think we all own kangaroos as pets. In fact, we’re beginning to see more diverse depictions of our homeland across a wider genre range of games, particularly from independent developers. Strewth!

International AAAustralia Games

Blizzard’s popular 2016 multiplayer shooter Overwatch remains a major game today thanks in part to its fun and diverse cast of characters. One such character is the deranged Aussie, Junkrat, an explosives enthusiast who also likes dressing up in a cricket uniform.

Source: Overwatch Wiki

In 2017, Blizzard added Junkertown, an escort map set in an irradiated Australian Outback, in addition to Sydney Harbour Arena as a Lúcioball map during the Summer Games event, edging out other potential locations Melbourne and the Gold Coast.

Junkertown is split into sections, which reflects the duality of Blizzard’s reimagined Australia, according to Dion Rogers, Overwatch’s Lead Environment Artist.

Concept art of a building outside Junkertown. Image courtesy of Blizzard Entertainment.

“After being kicked out of Junkertown, we wanted Junkrat and Roadhog’s new home/living situation to feel distinctly different, remote and somewhat low-tech,” Rogers said. “We referenced abandoned Australian woolsheds. The woolsheds feature rusted architecture, dilapidated wood and tin roofs which contrasts the colourful thicker metals and technology of Junkertown.”

Concept art of Junkertown exterior. Image courtesy of Blizzard Entertainment.

However, Junkertown was not without controversy. Blizzard copped some criticism in the wake of the map’s announcement, due to some clumsy narration which inadvertently drew parallels to Australia’s poor treatment of Indigenous and First Nations people. What drew the most criticism, however, was the inclusion of an in-game sign that read “take-out” instead of “take-away”, which was subsequently changed and addressed personally by Jeff Kaplan, Overwatch’s Game Director, via Reddit.

Fans singling out translation errors isn’t unique to Overwatch, either, with Ubisoft’s Rainbow Six Siege’s recently released Australian-themed Burnt Horizon content being picked apart for including some Americanisms – especially the distinctly non-Australian terminology of “gas” displayed on a sign outside of a petrol station. Ubisoft’s Australian team was swift in fixing this heinous error.

Guess who got “Last Chance Gas” changed to “Last Chance Fuel”.

You’re welcome, Australia. pic.twitter.com/PB3qFr8RFj

— Shane Bailey (@BaileyAU) February 13, 2019

According to Gregory Fromenteau, Siege’s Art Director, other settings considered for the latest content included bushland ghost towns, a Sydney motel, and underground Coober Pedy, before settling on the Outback as a location “fresh and out of the city”. Leanne Taylor-Giles, Aussie expat and a writer on Siege, said that the two new characters will add a good bit of “understated Aussie humour, and a little bit of taking the piss”. Mixed with Siege’s gritty take on the Outback, Burnt Horizon will no doubt make for some tense firefights.

Aerial view of Siege’s new map. Image courtesy of Ubisoft.

Arguably the most impressive depiction of Australia in a video game from a technical standpoint goes to the colour-drenched festival racer Forza Horizon 3.

After visiting Colorado, France, and Italy in the first two games, Forza Horizon 3 brought the Horizon Festival down under. Announced at the 2016 E3 conference, Forza Horizon 3 elicited two distinct responses from Australian fans of the series: first, sheer excitement at what was shaping up to be the best-looking game set in Australia. Second, what the heck is up with that map?

Playground Games took some generous liberties when designing their Australian geography – Byron Bay sits directly alongside The Twelve Apostles on the east coast, and the Yarra Valley is a casual five-minute drive from Outback Australia. Hilarious as the geographical interpretations are, they do make logical gameplay sense, as explained by Ben Thaker-Fell, Chief Designer of the Forza Horizon series.

“We tried to make sure the diversity [of locations] is spread out equally, so the player doesn’t feel like they’re spending ages driving through nothingness and it gives each location room to breathe,” Thaker-Fell said. “Ultimately, it’s a case of flow and diversity; we want to make sure the player is never too far from a fun and beautiful location in the world.”

Considering Playground Games is a UK-based studio, I was curious as to why they chose Australia as a setting before choosing their own backyard, now represented in the most recent entry, Forza Horizon 4.

“Ultimately, we chose Australia because of its incredible biodiversity which was something that shocked us when we investigated what the country had to offer as a location for Forza Horizon 3,” Thaker-Fell said. “We found such a rich collection of unique vegetation, geology formations, architecture and roads that it became abundantly clear Australia was a great fit.”

“We found the rainforests a real eye-opener as it wasn’t something we expected to discover and they’re easily some of the most beautiful parts of the country.”

Visually, Forza Horizon 3 is a love letter to Australia’s raw, natural beauty. Ironically, the video game that best encapsulates the vivid imagery invoked by Dorothea Mackellar’s famous “My Country” poem is one about driving expensive cars really, really fast.

Australia’s landscapes proved popular among Playground Games’ staff; Ormiston Gorge a particular highlight, and they were also proud of the work that went into The Twelve Apostles, considering the challenges associated with making such a geological feature in-game.

“[Ormiston Gorge is] an incredibly dramatic landscape and really pushed everyone both creatively and technically but the result was very satisfying,” Thaker-Fell said, citing the location as one his favourite exploration spots.

Ormiston Gorge as seen in Forza Horizon 3.

Most importantly, Forza Horizon 3’s authenticity extended to our wheelie bins, serving up prime driving destruction fodder.

“Thinking about it, over 10 million players have jumped into Forza Horizon 3 at some point – if they each on average drive into 100 bins, which feels conservative based on my driving, that’s a billion bins [run over],” Thaker-Fell said.

Not all of Australia could fit into the massive racing game, with both Sydney and the Blue Mountains considered but ultimately scrapped to ensure the best possible mix of in-game biodiversity and driving fun.

That’s okay though, we still have the “Outback” circuit from the 1997 Need for Speed II, which features Uluru right behind the Sydney Opera House.

Games From A Land Down Under

During the early 2000s, Australia’s Krome Studios hit success with the Ty the Tasmanian Tiger series in a field of heavyweights like Jak and Daxter and Ratchet & Clank.

The Ty series put you in the paws of the extinct animal, travelling through a fictional Australian setting inspired by country’s varied landscapes – with plenty of Aussie slang and ockerisms thrown around for good measure, too.

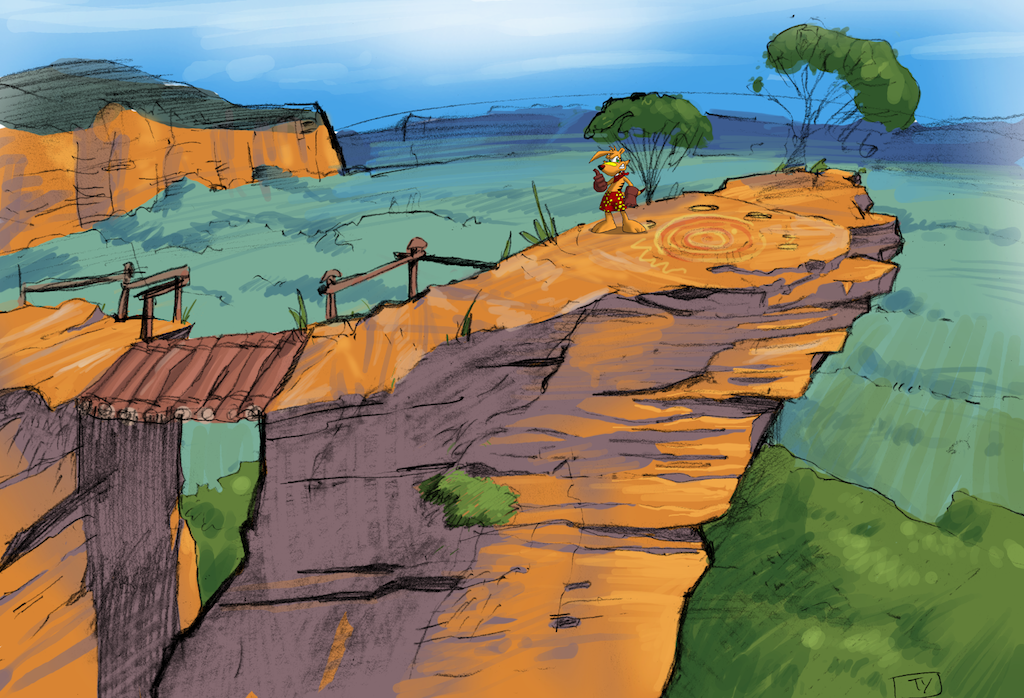

Concept art of Ty’s hub area. Image courtesy of Krome Studios.

The overall vision of Ty the Tasmanian Tiger had to meet international expectations of Australia, due to Krome reporting to an overseas publisher, while still retaining the developers’ authentic vision of Australia, according to Steve Stamatiadis, Krome Studios’ Creative Director.

“In the end, we picked a few [locations] like the Outback, Barrier Reef, Rainforest and Snowy Mountains,” Stamatiadis said. “Locations that gave us a nice spread of environmental looks and gameplay.”

“Though we did get a lot of pushback to using the Snowy Mountains because nobody in the US thought we had snow and, as such, thought it was silly.”

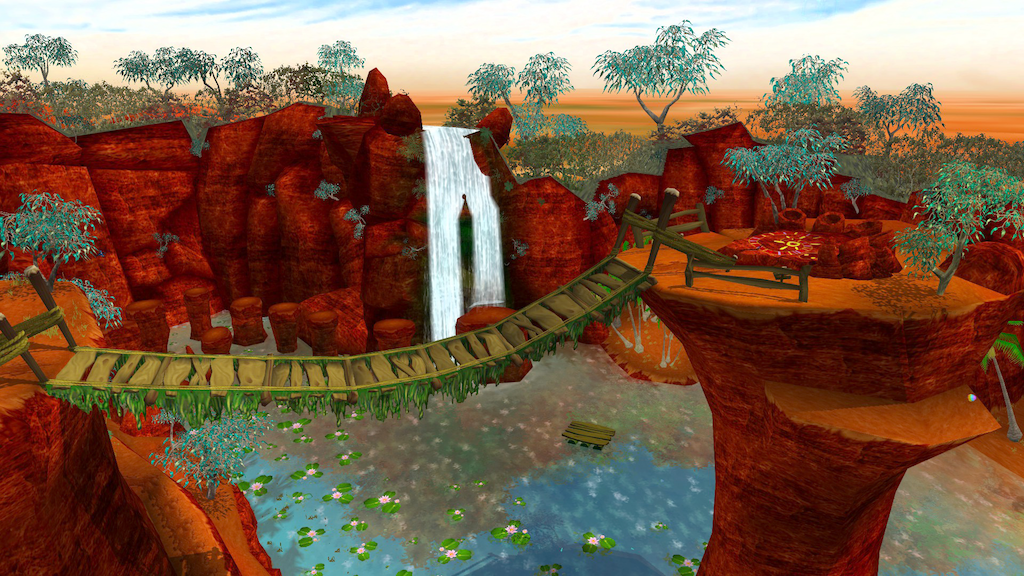

Ty’s hub area rendered in-game. Image courtesy of Krome Studios.

When populating the rest of the game with Aussie animals, the team chose what looked cool and hadn’t been used in a game before. These depictions included cockatoos, frilled-neck lizards, Tasmanian devils, plus a villainous cassowary known as Boss Cass.

“I did try to avoid having a lot of kangaroos because they’re so over-used as a shorthand for Australia, but I couldn’t help myself when it came to koalas,” Stamatiadis said.

More recently, we’re seeing games from local indie developers born out of a passion for writing about what they know, producing fascinatingly diverse experiences.

2018’s adorable Paperbark was made by Melbourne team Paper House, a game deeply rooted in an appreciation for Australia’s bushlands – and wombats. Originally a university assignment, the project took shape once the Australian setting was confirmed.

With much of the Paper House team coming from regional Victoria, it made perfect sense to set the game in Australia’s distinct bushlands, focusing on the unique native flora and fauna found while going bush.

“This country is a bit of a melting pot, with a bad history, but there is something about the bush that unifies – it’s the literal country and can’t really be disputed in that sense,” Terry Burdak, Creative Director of Paper House, said.

Authenticity is served by the bucketload in Paperbark through both function and form; the protagonist wombat’s short-sightedness plays into how the visuals unfold before your eyes. As if being painted in real-time, the game’s watercolour visuals generate the environment around you as you explore, reflective of a wombat’s field of vision.

Screenshot from Paperbark showing the wombat’s field of vision.

“The other nice thing about wombats, is they’ve been known to befriend people and take them on little journeys, kind of like your own personal travel guide,” Burdak said. “So [choosing a wombat protagonist] was also a really nice touch.”

Critical to Paperbark’s accuracy was ecologist Dr Emma Razeng who Burdak playfully refers to as Paper House’s “enviro-cop”, informing the team of what they could include to uphold authenticity. Burdak described the feeling of wanting to nail representation as not wanting to sound like the “really bad Australian accent in a movie” while ensuring the game had its own voice.

Well and truly speaking its own voice is another indie darling; the quaint golf-RPG hit Golf Story on Nintendo Switch. A favourite of Nintendo’s President, Shuntaro Furukawa, the Brisbane-based Sidebar Games title oozes Australian personality through its witty dialogue and Aussie cultural references – which inspired a video game cooking website to make a Sausage-Roll-In-One recipe. Not deliberately setting out to make an Australian game, the casual usage of “mate” and “sucked in!” made Golf Story immediately identifiable to Aussies, while generating some humorous results overseas.

“I saw an online post from somebody who said that they didn’t understand the game and were not enjoying it,” Andrew Newey, Sidebar Games developer, said. “They decided to watch both The Castle and Kath & Kim in an attempt to understand it.”

“It wasn’t my intention to show off Australian culture but I’m kind of proud of it now. I think I portrayed it accurately enough. I’m most pleased that I caused an American to watch both The Castle and Kath & Kim in earnest. Can’t ask for much more than that.”

In Golf Story’s finale, the camera zooms out, revealing that each golf course is arranged together to form the shape of Australia. Newey initially configured the game’s map into this shape as a joke, but it made the final cut.

“Everything seemed to fit well, so we left it that way,” Newey said. “Then we ended the game with a big zoom out so I could show off my handiwork.”

Golf Story’s map reveal. Image courtesy of Sidebar Games.

“The game wasn’t really meant to be set anywhere in particular but I guess the world map claims otherwise.”

Even looking at Golf Story’s courses, you can certainly draw comparisons to real-life; Queensland is tropical and beachy, Tasmania is freezing cold, and my beloved South Australia is depicted as a prehistoric wasteland.

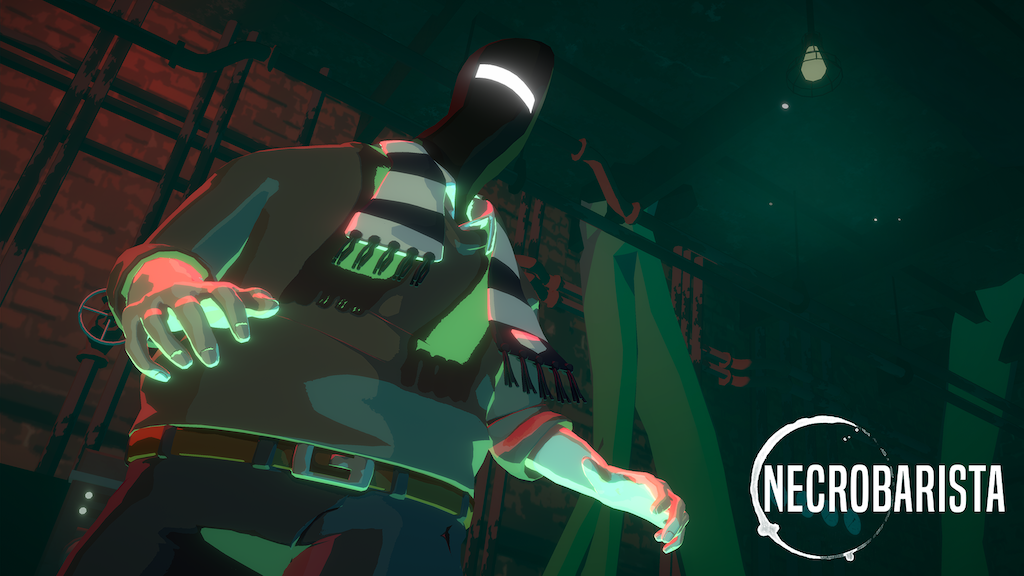

Beyond the broad depictions of Australia’s states and territories, it’s exceedingly rare to see Australian city life represented in video games – a void soon to be filled by the exciting upcoming cinematic visual novel Necrobarista.

Set in a fantasy version of metropolitan Melbourne, Necrobarista takes its inspiration from the coffee culture synonymous with the city, while also boasting goon-sack robots and an in-game appearance of a supernatural Ned Kelly. Kevin Chen, Lead Developer at Melbourne’s Route 59 Games, expressed surprise at the international appeal of Necrobarista’s non-stereotypical, contemporary setting, citing its novelty factor.

Ned Kelly as he appears in Necrobarista.

“You don’t see it very often, so one of the reasons we decided to set the game in Melbourne was because there aren’t any games we felt that were set in modern Australia,” Chen said. “You get a lot of the Ty the Tasmanian Tiger, that kind of Crocodile Dundee Outback Australiana stuff, but nothing about modern Australia, which aside from the novelty, means that we can draw from our own experiences.”

Playing the demo at PAX Australia last year, it’s striking how effortlessly Australian Necrobarista’s dialogue is, similar to how Golf Story’s writing is idiosyncratic of Australia’s spoken dialect. These games don’t overdo the “flamin’ galah’ stereotypes or depict us as a mob of crocodile wrestlers, instead favouring the subtleties such as how we naturally weave in a “mate” to soften the end of our sentences.

necrobarista is an extremely accurate depiction of the barista experience#indiedev #madewithunity pic.twitter.com/93SMKXLnyn

— ROUTE 59 GAMES ?☕ (@route59games) October 17, 2018

When looking at creating unique Australian depictions, Burdak encourages local developers to “take some risks and create projects where Australia can work as a setting”. One such risk-taking example came in the form of 2004’s Escape From Woomera, a controversial game designed to illustrate the plight of asylum seekers in Australia – harrowingly still as relevant today as then.

First Nations Australians Building A “Better Google Earth”

Even rarer than a non-stereotypical depiction of Australia, is an authentic in-game representation of First Nations people. This will soon be changing due to the work of Kooma man Brett Leavy, nominated for the CSIRO 2018 STEM Professional Career Achievement Award, and his team at Bilbie Virtual Labs. Working on a software toolkit known as Virtual Songlines, Leavy is aiming to create a “better Google Earth”.

Currently, approximately 37 separate experiences are in development as part of Virtual Songlines, which will be released via a Google Earth-like platform once completed. When complete, you’ll be able to go back in time to pre-European settlement and experience life as an Indigenous Australian. Leavy believes that the most effective way of explaining Aboriginal connection to country is through an interactive experience.

“What did Aboriginal people do to survive as they have, and how did they sustainably survive in that country?” Leavy said. “The best method I thought for [explaining survival] would be with a cultural survival game.”

“I think that’s the best way to immerse people in that space, to respectfully showcase that culture. To show where the permanent campsites were, to show where the propagation sites were.”

A 2017 version of one of the Virtual Songlines experiences.

Many of the in-development Virtual Songlines experiences revolve around survival mechanics; foraging and hunting for food, making shelter, and respecting Elders. By letting you interact in-game with the tools and resources used by First Nations people at the time, Virtual Songlines aims to break down the barriers of viewing museum collections from a distance, offering hands-on learning experiences.

Leavy’s rationale behind developing so many separate digital experiences instead of one big game is due to the diversity of Australia’s many First Nations groups, all with their own languages and customs.

“In Australia, everybody wants to see Aboriginal people as one big homogeneous mob, but in a sophisticated world, respecting all those different cultural enclaves, there’s over 301 in Australia, I can tell you right now,” Leavy said.

A still from the Virtual Warrane experience. Source: Virtual Songlines

Seeing more authentic Indigenous Australian representation in games requires opening pathways and encouraging more First Nations people to get involved in making games. Several initiatives in recent years aimed at Indigenous youth may see more people telling their stories through games. In 2016, the Australian Indigenous Mentoring Experience (AIME) received funding from Google to run a week-long STEM program including students pitching a game idea, which ended up becoming mobile game Second Chances.

2019 will see Indigenous entrepreneurial group Barayamal run the “Give Backathon Game Jam” in Melbourne on April 13, where aspiring coders will be encouraged to develop a game to inspire Indigenous youth how to develop their own games.

As shown by these games, while many favour Australia’s iconic red centre as a setting, there is an increasing amount of games showing off our cosmopolitan nation. With plenty of AAA games visiting our shores, local indies creating grounded and personal experiences, and some exciting Indigenous projects in the works, there’s a lot to play and look forward to for your interactive Aussie fix.