Are We Making Any Progress With The ‘Male-Dominated Degree’?

"I think there have been good initiatives... But it seems these have not yet affected the way women are treated once they’re in these subjects.”

Picture a biomedical engineer. Now, a computer systems analyst and a neuroscience statistician.

A few decades ago, you probably would have imagined three men. Today, you might not.

In 2017, the days of science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) degrees being ‘boy’s clubs’ are supposedly over. Scholarships, mentoring programs and nationwide funding to encourage diversity in STEM are pretty visible nowadays; plastered to university pinboards and filling the inboxes of young female students.

But are efforts towards gender equality in traditionally male-dominated degrees actually making a positive change?

What Do The Stats Say?

In short, the data says no. Most fields of study are still plainly skewed along gender lines.

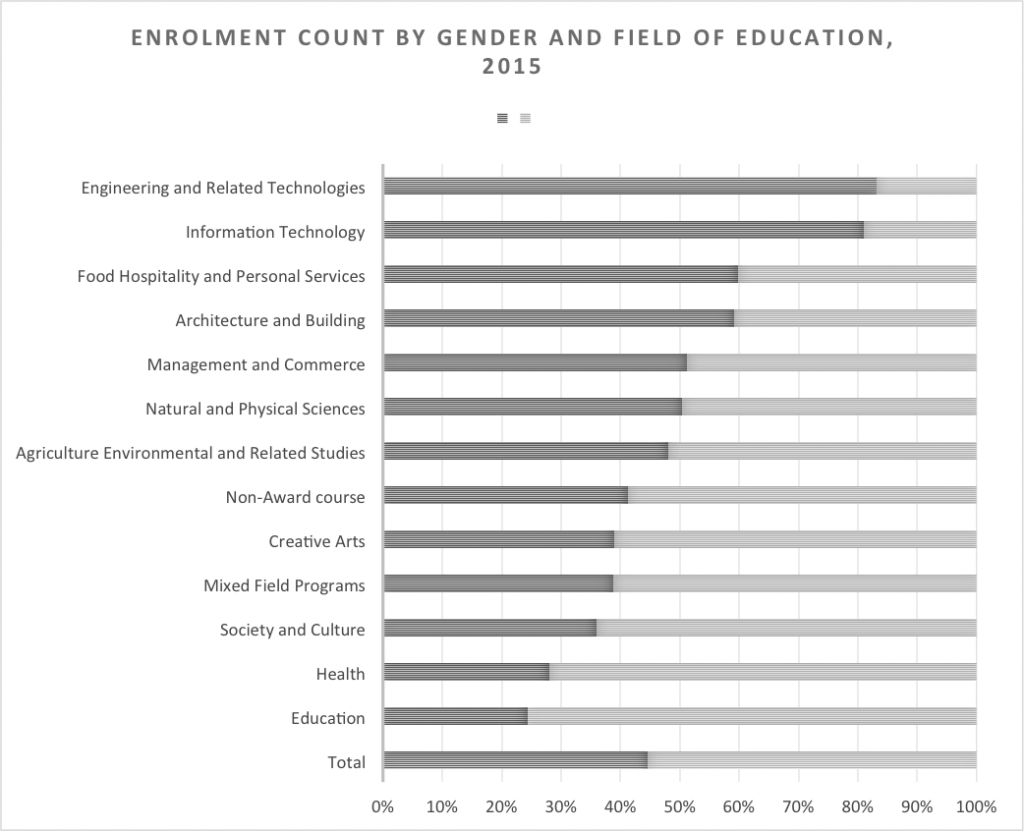

In 2015, women made up majorities in Education, Health, and Society and Culture courses, but were still seriously underrepresented in STEM.

Just one in five Engineering and Related Technology students enrolled in 2015 were women and less than one in four for Information Technology courses. For females studying STEM at university, this is a serious concern.

Source: Department of Education and Training Higher Education Statistics, accessed 5-10 September. Note: Trans and gender diverse identifying students did not have a clear option to record their gender as such in the survey methodology, and therefore are not represented in the results.

The Elephant In The Room

Sophie Ryan, currently studying a Bachelor of Computing Science (Honours) at the University of Technology Sydney, says the lack of female representation in her course makes it more challenging.

“It feels a lot like there’s something you need to prove. You find yourself spending your time making sure people you don’t like will listen to you,” she says. “Group assignments take longer than they ought to because your contributions are constantly reviewed.”

“Watching your group members come to the same conclusion as you by starting from a position of distrusting your conclusion wastes time.”

It’s clear that this is a real problem for women and gender diverse people studying in STEM fields, often not only in their day-to-day lives but for the span of their educational and professional careers.

“Group assignments take longer than they ought to because your contributions are constantly reviewed.”

And it’s a problem recognised globally, by bodies from the United Nations (which designated February 11 as the annual International Day for Women and Girls in Science) to the Australian Government and the CSIRO.

There are plenty of programs designed to get women engaged in STEM, and some more widely targeted at minority groups, such as the Science in Australia Gender Equality Program, of which Sophie’s university is a Charter Member. Australia also has the government-funded Superstars of STEM initiative, Code Like A Girl, SheFlies and Robogals as well as numerous regional projects.

But the statistics are clear: female representation in most STEM degrees haven’t really increased over time. Just 16% of university and VET STEM graduates remain women. And if you look at the enrolment count by gender in IT, Engineering and Natural Sciences, significant progress has occurred only in Natural and Physical Sciences.

But why?

Beyond The Initiatives

Aeronautical Engineer Anastasia Volkova speaking at TEDxYouth Sydney 2017. Photo: TEDxSydney/Facebook

Government releases attribute the lack of women in STEM to gradual ‘attrition’, stating: “Australia loses female talent at every stage of the STEM pipeline despite no innate cognitive gender differences.” It recognises that females become less and less likely to be involved in STEM due lack of engagement, confidence, and bias.

The Office of the Chief Scientist proposes four key steps towards gender equality in STEM: eliminating stereotypes and biases, emphasising real-life STEM applications in teaching, rewarding hard work and building confidence, and encouraging organisations to create and monitor inclusive workplaces.

Sophie agrees there’s still a lot of work to be done. “I think there have been good initiatives to encourage more women to do FEIT (Faculty of Engineering and Information Technology) subjects,” she says. “But it seems these have not yet affected the way women are treated once they’re in these subjects.”

And it’s not just females being affected.

University of Sydney second-year student, Jako Playford, thinks a gender imbalance hurts everybody. Studying a Bachelor of Engineering Honours (majoring in Biomedical Engineering) and a Bachelor of Arts combined degree, he says a gender gap is a lot more noticeable in his ‘traditional’ engineering subjects.

“It definitely negates the learning experience. The classes where there is a more neutral ratio just seem to have a good balance to them. Whether this is real or implied I don’t know, but the classes dominated by males feel less positive and less receptive,” Jako says.

There’s Still A Way To Go

It’s clear that both the stats and the students are telling us we need to up the ante. Alongside current efforts aimed at including women and minorities in STEM, more needs to be done – and there’s plenty of ideas out there.

Diversity isn’t just a responsibility, it’s a strength.

Jako believes role models can be a powerful tool. “Promoting the work of females in the field who are doing cool things would go a long way to removing the stigma,” he says. Telling young people they can create change and achieve results regardless of their demographic is important, he says.

Diversity isn’t just a responsibility, it’s a strength. It means drawing from a wide range of brilliant and unique minds to solve our problems. And with seriously problems on the horizon for mankind – such as climate change, overpopulation and avoiding nuclear war – we’re going to need all the brainpower we can get.

(Lead image: Mindy Project/Hulu)