A Sexy, Sexy Lesson In Australian Copyright Law: Fact-Checking The Creationistas

There's a copyfight brewing in Australia over the future of copyright. Those in favour of less strict laws have had their say on this site. Here is a response.

There is a copyfight brewing in Australia over the future of copyright in the digital age. It has on both sides taken on the tenor of religious fervour, like we’re arguing about the existence of God. But it’s much less an argument about belief systems (I should be able to take whatever I want for free versus you should have to pay for the things you want) than it is one of pure commerce: there are commercial concerns on each side that are at cross-purposes, and between them lies the fate of creativity on the Internet.

Those in favour of less strict copyright laws have had their say on this site; in a piece published in Junkee earlier this month, Dan Ilic — who created the Creationistas campaign for the Australian Digital Alliance — argued that the Fair Dealing provisions of Australian copyright law need to be loosened, to catch up with the digital revolution and, in his view, facilitate more innovation online.

I disagree with Dan’s take on this, and have issues with some of the facts presented in his piece and the Creationistas’ campaign. What is really at issue is not the creation of culture online, but who makes money from it.

On the one side are the creators: the people who make the culture we consume and the various businesses which make that creation possible. On the other are the companies whose business models rest on the generation of new digital content. The more people who pay creators for the work, the more work that can be created. The more content that is uploaded to the Internet, the more tech companies earn from revenues generated by pageviews.

Great fortunes are being made and lost. People on the side of the Internet — including the Australian Digital Alliance — like to call this disruption. People on the other side, like me, call it destruction.

What Is This Article About, Please?

There is currently a push spearheaded by the Australian Digital Alliance to introduce a Fair Use provision to replace Fair Dealing in Australian copyright law. The ADA represents the interests of a good number of educational institutions, yes. It also represents the interests of ISPs and other big tech companies like Google, for whom one of its directors works.

The Australian Law Reform Commission is undertaking a review of copyright law in Australia, looking at how it affects the digital economy and whether changes to the Copyright Act of 1968 are required. The advisory committee, however, did not include a single professional member of the creative industries. It did include representatives from Google, Facebook, the Australian Digital Alliance, the Internet Industry Association and the Australian Communications Consumer Action Network; four board members of the Australian Digital Alliance; two representatives of bodies that prepared reports for the Australian Digital Alliance; and three academics who are publicly advocates in favour of a US style fair use exception. In their submission to the inquiry, the Australian Film & TV bodies argued that this called into question the ALRC’s Independence from government, party politics, academic interests, special interest groups and other stakeholders.

All the submissions can be read here. The finding will be delivered on November 30.

What is Fair Use vs Fair Dealing?

Fair Use, which the Australian Digital Alliance and the Creationistas are lobbying for, is a doctrine of US copyright law. In Australia we have Fair Dealing provisions which are not as broad, but which strive to strike a balance between the rights of creators and their ability to earn an income from their work, and the interests of the public sphere, where culture exists and where work is created that uses or references other people’s creative works.

Unlike in America, there is no provision in Australia for “transformative use”, a malleable term that can be legally applied to mean a great many things. But that’s not a problem in Australia, where – under Fair Dealing — we have many other ways to legally use someone else’s work in the creation of our own:

— Criticism and review: For the purposes of reviewing or criticising a work, part of that work may be excerpted without paying a licensing fee.

— Parody and satire: For the purposes of commentary, parody and satire, again a work can be freely excerpted, as with an Internet meme, which is usually providing a satirical or parodic commentary on the subject of the meme.

— Reporting the news: Broadcast work created in aid of reporting the news and current affairs can be excerpted freely.

— Insubstantial use: Using a small part of a work that falls within certain parameters does not infringe copyright.

— Seeking permission: You can just, through regular old politeness, ask someone if you can use their work. If it is for non-commercial purposes, because they like the project or you yourself, the creator might agree to a $1 option for the use of their work, and waive their usual fees. Or, as often happens with artists whose music is sampled, by striking an arrangement for future earnings against any ensuing sales generated by the new work. This is especially common in hip hop sampling. Try asking before you just take something and see what happens, today!

— There are also numerous specific exemptions, including, for example, for educational institutions.

— Creative Commons licenses exist for artists to manage themselves the rights they assign to their work and how it can be used by others.

The Problem With Fair Use

Anything that doesn’t fall under these categories has to be licensed, and the creator must be compensated by someone who wants to use their work. HOW CRAZY A CONCEPT.

Except it’s not. Authors’ moral rights override commercial rights; if an author feels their moral rights have been contravened by someone else using their work in way they don’t feel reflects fairly on their work or disparages their character, they have grounds for legal action regardless of how the work was licensed by the new creator.

Of 167 countries subscribing to the international copyright community, only four countries (the Philippines, Korea, Israel and the US) incorporate Fair Use. Fair Use would decrease the ways in which creators could be compensated when others use their work. As the US law itself specifies, “There is no specific number of words, lines, or notes that may safely be taken without permission.” This sentiment is directly tied to the free culture movement, where the rights of consumers are prioritised above the rights of artists. Artists have the right, as enshrined in copyright law and under human rights, to make a living from their work, and to decide who can and can’t use their work and under which circumstances.

Culture has thrived perfectly well under these conditions for the last 300 years of copyright law. There is no reason that the Internet requires special changes be made to copyright law other than because the companies whose interests that position serves have very successfully campaigned for it.

Fact-Checking The Creationistas

I sought the advice of Gilbert + Tobin lawyers in Sydney to get caught up on the finer points of interpreting copyright law in Australia, with a specific look at The Creationistas’ campaign.

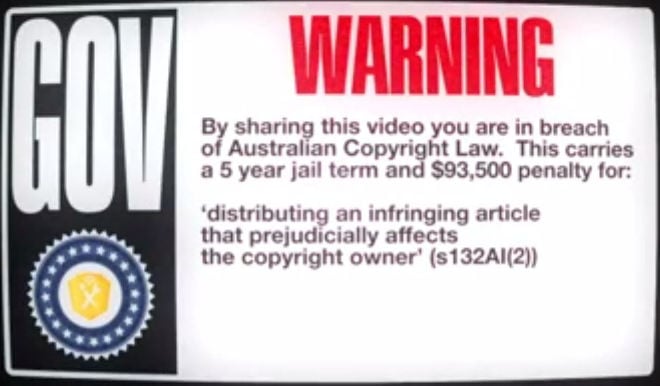

Catchy opening! But it’s not true, as the video itself states a second later. This bait-and-switch makes for a clever opening, but it’s misleading; and it’s this kind of muddying of an already dense and confusing area of law that I have a problem with. Using other people’s work is precisely about seeking their permission. Have their permission and you can share all you want. Don’t have their permission and you can’t. That is the creator’s fundamental right: deciding how their work is used.

It’s not illegal to share the video, as the creators, the Creationistas, have expressly authorised for the video to be distributed via the big button on the campaign website underneath it, labelled, “Share”. That means the authors have allowed the work to be shared without financial compensation to them. No law is being broken here.

“Creating a search engine in Australia would be impossible. That’s a breach.”

Again, this is clever, but untrue. Google successfully operates in Australia every day, free of any threat of legal action.

“What if I told you that in Australia, this new way of sharing, communicating, remixing is illegal?”

You can tell me that, Dan Ilic, old colleague and personal friend, but it isn’t. Copyright under Australia’s Fair Dealing provision is not infringed by posting authorised YouTube links, remixing insubstantial parts of a work, or otherwise dealing with copyrighted works in any of the authorised ways mentioned earlier.

“So for Halloween, your Mum’ll be pimping you out in Mario Bros outfits. Your mama didn’t get no licence from Nintendo and that breach I’ll be a breach yo!”

No, it’s okay. Your mama will only be in breach if she copied Nintendo’s copyrighted drawings or those of a costume supplier.

Why Should I Care?

If Australia were to introduce a Fair Use exception to replace Fair Dealing in our copyright laws, the main beneficiaries would not be individual creators anywhere near as much as it would be tech giants like Google and Facebook, whose market value grows in accordance with their traffic figures and time spent per user on their sites, and who rely on indexing other people’s work to create their products.

The more content added to the Internet, the more traffic they will get, and the more money they will make. This results in multi-billion dollar values for those companies, and free services for the users. It doesn’t result in monetary compensation for users, despite their content creation directly benefiting the bottom lines of a corporation (excepting when creators monetise their content with pre-rolls or other advertising, in which case you cannot profit from sharing someone else’s work without permission without facing prosecution even under Fair Use, because that is illegal — and no changes to copyright law would change that).

As a creator, you are not being discriminated against by copyright law. Copyright law protects your livelihood. If, as a creator, you want to use someone else’s work to make a new work, you pay them for the right to do that. Just as if someone wanted to use your work to profit from, they would have to pay you. You do not get automatic rights to someone else’s work, just because you want them, even under Fair Use. Culture isn’t free just because you want it to be. If you can’t afford to license the work you want to use, then perhaps you need to come up with something original in its place. Obstructions, being forced to innovate, are what truly spur creativity.

You do not get automatic rights to someone else’s work, just because you want them. Culture isn’t free just because you want it to be.

It’s tempting to watch a very slick four minute video as opposed to reading through a tonne of legal papers, but that’s what’s required to understand what’s really going on with this stuff, to differentiate between fact and myth for yourself.

Lobbying for transformative use for non-commercial work might, on the face of it, look like a victory for bedroom producers everywhere, but it’s not that simple. Yes, you can make a cool video to share with your friends, but it’s not your friends, or in most cases you, who’ll make money from the pageviews.

Corporations like Facebook, Twitter and Google go to great lengths to make their brands appear as non-threatening, laid back and quirky as possible; Google with its doodles and multi-coloured logo, Twitter and its cute little bird, Facebook’s trusted, dependable blue — they all paint a consumer-facing front of ineffable efficiency and cool, frictionlessly useful products that are all in the spirit of openness, collaboration and creativity. This is the face of the new corporation, and its pockets are very deep. Far from loosening copyright in the face of lobbying from these companies, we — as creators — need to ensure that it stays strong.

–

Elmo Keep is a writer and Digital Director with The Lifted Brow. She is a public advisory committee member of the Emerging Writers Festival, and consultant with the Intellectual Property Awareness Foundation.

Feature image: ‘Copyright License Choice’ by Opensourceway, under Creative Commons.